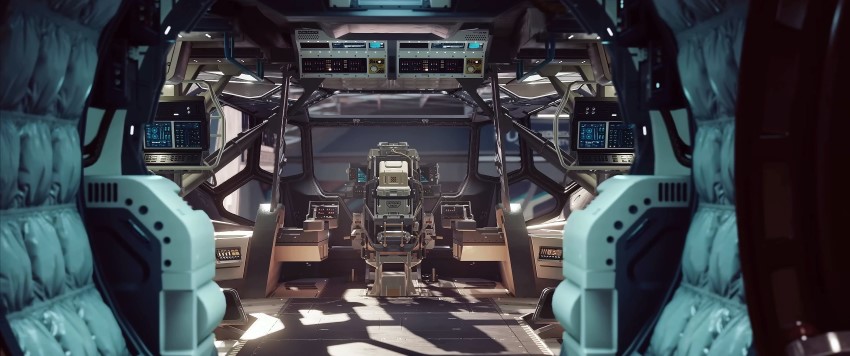

Bethesda Game Studios’ first-person space RPG Starfield – available now on Xbox and PC – takes players through the epic void of space to unique planets and cities. In addition to completing side quests and main mission objectives, players can build their own ships, develop their own outposts, hunt down bounties, and much more. There are seemingly endless possibilities for adventure and mayhem.

Each location has a life of its own – literally! From unique planetary biomes to lively nightclubs, the sound of every spot in the entire universe of this game was hand-crafted, as was the sound of each player’s unique ship that isn’t just transportation from destination to destination but acts as the player’s home. The player can choose from different helmets and suits, all of which change the sound of the dialogue and foley.

There is a universe’s worth of creatures, a ton of weapons, and a bunch of robots – all needing individual and specific sounds.

Here, Bethesda Game Studios’ sound team members: Mark Lampert (Audio Director), Casey Coffman (Senior Sound Designer), Dave Schreiber (Senior Sound Designer), Frédéric Tardif (Senior Sound Designer), Jerry Schroeder (Senior Sound Designer), Cazz Cerkez (Sound Designer), and Richard Evans (Sound Designer) discuss their ‘divide and conquer’ approach to designing ambiences, crowds, creatures, weapons, and ships over the 7-year development of the game, and how sounds evolved as the game did. They talk about foley, robots, vocal processing, and much, much more! Plus, they talk about their technical challenges, like switching from proprietary audio tools to middleware halfway through production, and creative challenges like designing special abilities (*WARNING: Spoilers in this section*).

This epic game deserves an epic Q&A! We hope you enjoy this enlightening journey into the sound of Starfield.

SPOILER ALERT: Answers containing spoilers are noted in Q&A below

Starfield Official Gameplay Trailer

Starfield was in development for over 7 years?! What were some of the first elements you tackled sound-wise? Did those sounds end up evolving or being revised over the course of development? How did they evolve?

Dave Schreiber (DS): The Cutter weapon is the first weapon the player encounters at the beginning of the game, and is one of the first things I worked on. It evolved quite a bit over time, and the audio experience evolved as well. Iteration is often a key ingredient to the game audio process. However, I’ve lost count of how many iterations the Cutter had, haha. I transitioned DAWs and audio engines while working on this weapon.

My first approach for audio started out as a laser gun as you might imagine it: Zap zap. However, it lacked solid feedback, it was more combat-oriented content, and early on it became apparent this was not the right approach. Since it is the first weapon the player encounters in the game, it’s important for it to feel tight and right. Plus, it’s a tool that’s infinitely useful for mining and exploring the galaxy throughout the rest of the game.

The main player firing content feeds into some real-time effects when intensity is high…

I eventually decided that it was a tool first and a combat weapon second. Ultimately, the audio experience needed to be more tool-oriented than combat-oriented. That was a major shift.

Plus, this was one of the more technically challenging weapons. There is all manner of interactivity the player has with it. The main player firing content feeds into some real-time effects when intensity is high (LT button increases intensity) – distortion mostly in this case. Aiming down sights triggers a one-shot when the beam intensity reaches a certain threshold, as well as modulates the player firing content – more distortion and other effects. The ammo count is calculated in real-time and I used that to modulate various content, effects, and layers. As ammo decreases, the weapon gradually feels much more unstable and overheated (distortion, pitch, rhythmic ticking increases in frequency) until the moment the ammo is out or the player releases the trigger. It was really a delightful weapon to work on despite its challenges and technical complexity.

Casey Coffman (CC): The very first thing I tackled was Heller’s half-helmeted line at the very beginning of the game. As you ride down the elevator with him and Lin, they banter back and forth a bit and Barrett equips his helmet in the middle of a line – something we’ve not had to support before. Initially, this was tackled as just an offline process with a bit of distortion and bandpassing. When we later got Wwise support online for VO and helmets, the line was rendered out in Wwise and spliced, but still technically an offline file.

…over time it became clear that the animation and the VO line just weren’t ever going to remain in sync…

Every few months the timing seemed to change and the offline render would have to be updated, but over time it became clear that the animation and the VO line just weren’t ever going to remain in sync, and could drift pretty wildly from one another. When we realized this desync was going to happen regardless, and potentially be different for every user, I wound up tackling this with real-time processing in Wwise and some bespoke data in our tools and animation. Now, regardless of when he equips the helmet, “it just works.”

Frédéric Tardif (FT): The first thing I worked on was the Rattler pistol sounds. The third revision (that happened over the years) is the one you can hear in-game right now.

Mark Lampert (ML): I’ve usually started every game project the same way, and that’s with the sound design of the ‘UI’ – the most basic functions of the menus in which the player will be spending plenty of time – and usually from the simplest, most common actions such as clicking ‘ok / yes,’ ‘cancel / no,’ and the most frequent of all, the little tick or blip of the ‘focus’ sound as the player cursors over any given menu option. These aren’t glamorous or big feature moments, but players will hear this stuff constantly, and I want to start playing around with what ‘affirmative’ or ‘negative’ really feels like.

…I want to try and use the same source elements so that everything feels unified and related.

I come back to this same project again and again, not just to revise these basic UI sound effects as I spend time with them in the game, but also to spin off new UI sound effects as the game develops and we then need the sound of ‘previous / next’ in menus with multiple pages, or perhaps more advanced functions like assigning skill points, dropping items, entering special modes, etc. The point is that I want to try and use the same source elements so that everything feels unified and related. In the case of Starfield, all of that source audio was button presses and clicks, little ticks of a hard drive being read, electronic beeps that I’d produced with various pieces of gear and things like that – elements that I felt would fit the game’s universe and the look of its menus. If it had been a fantasy game, I’d focus on more physical elements like touching paper, page turns, the click of a small key in a lock or a button snapping shut, the light tap of a blade, and things like that which would be appropriate to that kind of universe.

Starfield has a truly massive in-game universe to explore, with more than 1,000 planets to discover. How did you handle the ambiences for all the different locations that players can explore? Being that there are so many locations, and all need to sound unique, how did you divide and conquer this amount of work? And, how do you keep the location ambiences from sounding samey?

ML: I’d love to let the other guys answer this one. I did a lot of ambience work in our previous games, but I only created the initial ambiences in Starfield before just handing over the reins to the team and letting them run with it. I was really pleased with the result of everyone taking a few of the game’s biomes each, and especially with having each designer take one of the larger cities and completely make it their own.

…I only created the initial ambiences in ‘Starfield’ before just handing over the reins to the team and letting them run with it.

Everybody approached their city a little differently, and I realized that it doesn’t matter whether that approach and result are completely consistent; it’s the uniqueness of each location that is enjoyable and memorable to the listener.

Richard Evans (RE): For the planets, rather than tackling the work by planet, we broke it down by the number of possible biomes. Each biome has lots of variations, and those variations are what get assigned to the numerous planets. Each of the biome variations is unique, having distinct-looking plants, rocks, and other geological features. We made sure each biome had its own unique wind flavors, various types of plants got their own unique leafy rustles, and biomes with life got some unique unseen wildlife sounds. In the barren volcanic biomes, you can hear seismic activity as the planet rumbles beneath you. In the desert, you can hear sand whipping through the air, and in the high altitude of the mountains, the wind is more blustery and you hear the occasional rockslide.

The types of wildlife you hear in each biome change based on day/night cycles and the current weather.

To keep things sounding interesting and rich, we wanted to be sure that the world around the player transmitted lots of various layers of audio in different ways. Some of that unseen wildlife you hear plays with random positionality around the player, making them feel like there is life existing around them, while other parts of the wildlife audio you hear plays from the location of foliage. The types of wildlife you hear in each biome change based on day/night cycles and the current weather. Extra layers of snow, sand, or other particles get layered into the various biomes’ wind flavors, and the wind’s intensity changes based on time of day and weather. The sound of the wind’s gusts actually triggers the audio for procedurally placed things like leaves rustling, tall grass swaying, the sound of sand and pebbles blowing against rocks, and the occasional odd-shaped rock formation whistling away.

DS: The ambience work was split among the audio team, and we each made our contributions. At a high level, we needed to develop more procedural ways of implementing ambience content throughout various biomes, cities, areas, etc. I cannot commend the team more on the ambience work that went into this project. It truly is stellar. This was unlike any of the previous Bethesda projects I’ve worked on in my time here. There are still a lot of manual touches throughout the game, and I worked extensively in New Atlantis. Aesthetically, I wanted that space to sound very clean, fresh, and proper.

Similar to the cities and biomes, we divided and conquered the dungeons, caves, and other points of interest that the player can explore.

Cazz Cerkez (CCz): Similar to the cities and biomes, we divided and conquered the dungeons, caves, and other points of interest that the player can explore. There’s a wide variety of interior locations so we had a lot of ground to cover. When it made sense to do so we shared some sounds throughout multiple locations. Having the ambience of things like computers, vents, room tones, and machine hums being somewhat consistent helped establish a sense of familiarity with how interiors in this universe sound.

On top of having those sounds in as a base layer, we added unique sounds for character. For example, a frozen lab would get sounds of cracking ice, ice debris falling, cold interior winds, etc. All of which help bring the environment to life.

There are five main cities in Starfield: New Atlantis, Akila City, Neon, Cydonia, and The Key (space station). Can you talk about the aesthetic for sound for each city? What are some of the main sonic attributes of each city (like crowds, or the sophistication of their tech?) What are some low-key sonic elements that add to the unique vibe of each city?

CC: For Cydonia, we knew the place was going to be a huge sprawling metal behemoth on the surface of Mars. It was important to get a lot of the structural rattle and rumble locked in early, both for things like the massive crane tower outside, to subtle details like the various catwalks that creak from time to time. A small detail I added here that I really like is when you’re near any of the exterior facing windows you’ll hear the sound of the sand storms raging against them, slinging debris against them and whatnot. Later into the development of the city, I paired up with Richard to get some of the Walla system content in and functioning as a bit of a finishing touch to help sell how busy this compact space can get.

…when you’re near any of the exterior facing windows you’ll hear the sound of the sand storms raging against them…

Also, there’s a “subterranean particle detonation” that happens in and around Cydonia. For this, I’d set up initial explosions in the distance with a sort of “shockwave” effect that travels from that detonation point and ripples past the player off into the distance – all while also playing localized rattling sounds from nearby objects in the level – if you’re in the bars you’ll hear glasses clink and chairs rattle, if you’re near windows/doors you’ll hear them rattle, any of the fencing in the interior will rattle, and so on.

DS: Crowd walla was a new ingredient to making cities, ambience, and populated areas feel lively. Shout out to sound designer Chris Hite for his early collaboration in fleshing out initial concepts with me on that tech vision. After early tests, we determined that it was worthwhile to pursue. It added liveliness that was dynamic enough to suit most situations.

Everyone on the team had a hand in the walla treatment as it basically became part of everyone’s ambience work.

Everyone on the team had a hand in the walla treatment as it basically became part of everyone’s ambience work. Another shout out to Richard [Evans]. There were edge cases where he came up with clever solutions and also carried walla over the finish line in many ways.

Additionally, I think most audio team members have some amount of diegetic music in the game. That was great fun to work on. Everyone’s musical influences can really be seen in those encounters, and it adds a lot of variety to these areas.

FT: The Well in New Atlantis ended up being a small hidden city under New Atlantis. The place is a bit rough and people living there don’t necessarily have it easy, so it was nice to design ambient sounds that would match this feeling. The music score that plays in this area is very sparse and ambient, since I wanted to give space to all the shops, bars, and restaurants that have their own music.

For Neon, it was a lot of fun to create the music for all the various clubs in the city, and I tried to give each club its own flavor.

For Neon, it was a lot of fun to create the music for all the various clubs in the city, and I tried to give each club its own flavor. For the Astral Lounge, I was inspired by Trance mixed with some Electroclash elements, to create some sort of cold, hypnotic, and uplifting music. Madame Sauvage’s sound is a bit more aggressive, raw, and guitar-driven. Euphorika is more like classic lounge music (with a bit of French-house flavors). There’s also a private area in Euphorika with a unique set of slow, trippy music for people who want to consume Aurora quietly. Combined with all the awesome ambience work that Richard did on this city I think Neon has a very distinct flavor.

RE: Fred (Frédéric) nailed the music for the clubs, which are such an iconic part of the city. Neon is a very dense and active city; there is an overload of bright colors, an abundance of drugs and crime, a big fish-processing plant, big shady corporations, and a shopping district where stores are playing their advertisements into the streets. It’s constantly storming, and it’s all stacked up on a little fishing rig out in the middle of an endless ocean. I wanted the city to sound overwhelming, dirty, grimy, electric, sonically dense, and wet.

In the interior, Casey did the work on the advertisements you hear on the main drag. I wrote some music for that Neon sign above you when you enter the city, and of course as you walk in proximity to the clubs, you hear Fred’s music low-passed and thumping through the streets.

The idea was for the audio to be constantly grabbing at the player’s attention from every direction.

Everything creaks and squeaks from the rust. The streets sound like an overly crowded shopping mall. The lightning strikes occasionally trigger the city to rattle. The gutters have the sounds of water trickling through them, and everywhere there is the sound of a subtle electrical hum. The idea was for the audio to be constantly grabbing at the player’s attention from every direction.

When you’re in the exterior of the city you get the sound of the waves crashing below, the sound of rain hitting against all the metal, deep groans as the city sways in the wind, ships landing and taking off from the landing pad, and when you’re on the rooftops under the dome, you hear the rain pattering against the shell above you.

ML: I did have one contribution to The Key which is in its bar, the Last Nova, where you can hear what sounds like a death metal band playing over the PA system. It was a little side project of an idea that I tested out very early on in Starfield’s development, making a quick proof-of-concept track to see if I could pull it off and make it sound right in the environment, and then much later on returning to that project and rapidly banging out the rest of the tunes.

My concept was a band called ‘Trash Planet’ that’s made up of new Crimson Fleet recruits.

My concept was a band called Trash Planet that’s made up of new Crimson Fleet recruits. They thought they were tough guys when they joined up, but really they’re a bunch of whiners who can’t handle the rigors of life in space, so they complain about it in their music. Each song’s lyrics revolve around a different aspect of what’s tough about space: the darkness, weightlessness, the coldness, the vastness, and the vacuum. Not everyone is cut out for life in the Fleet.

VIDEO: The Sound of Adventure – with Audio Director Mark Lampert and Starfield Composer Inon Zur

Each song’s lyrics revolve around a different aspect of what’s tough about space: the darkness, weightlessness, the coldness, the vastness, and the vacuum.

CCz: Akila is probably the most stripped and natural city out of the bunch. Home of the Freestar Rangers, it has an old West/American frontier vibe to it. Keeping that in mind, it’s sonically very different from the clean city of New Atlantis, or the vibrant Neon. There are no club bangers or billboards playing advertisements. Instead, I leaned into the natural sounds from the biome (wind, sand, dirt, and debris) as the base layer and added character layers for the city on top of that. Things like walla, farming machines, water running through gutters, insects buzzing around bushes, creaky wooden guard towers, and shops, all the while focusing on keeping the city pretty natural sounding.

What was your approach to sound on the Data Menu? (The menu where the player can check out their ship, skills, quests, location, etc.)

ML: That Data Menu is the sort of “main intersection” through which the player is always going to pass before they branch off into one of many avenues. A lot of the aesthetic of Starfield’s menus has a very computer terminal look to it, so I generally aimed to make it feel like you were looking at a computer screen, hence the basic UI functions have a little bit of a button press click baked in, and each screen has its own ‘open / close’ in which there are some old school CRT television elements used, including a little bit of that static crackle that you would hear with an old television.

…art director Istvan Pely’s whole ‘NASA punk’ idea really influenced me…to use a lot of older electronic source material.

Even if it didn’t always apply, art director Istvan Pely’s whole “NASA punk” idea really influenced me in cases like this and gave me a sort of permission to use a lot of older electronic source material. It’s really fun from a sound perspective to be able to use those more relatable physical sounds from older electronics, magnetic relay switches, clicky toggle switches and button presses, and things like that, as opposed to trying to do something purely synthetic with no real-world analog.

It might be a fun idea for the community to try pitch-shifting some of this content to see if they can hear any musical easter eggs.

DS: Like Mark said, he really defined and nailed down the UI elements early. My job was quite clear when it came time to contribute towards the dataslate, and digipick. It was great to reference his work for my tasks.

I started out doing less physical content for those pieces and Mark would give great feedback on incorporating physical content as layers: switches, knobs, button presses, etc… It might be a fun idea for the community to try pitch-shifting some of this content to see if they can hear any musical easter eggs.

What went into the player’s ship sounds? Did you capture any custom recordings (like switches and knobs) for these sounds? Were there helpful libraries – maybe for the rocket/burn sounds?

CC: The engine set I worked on, Reladyne, is fictionally the set most closely resembling the jet engine and rocket technology we see in our own world today. As such, a lot of this was blends of various library content of actual engines, rockets, and also things like fireworks and other grounded and real explosions.

In general, the goal here was to have things loud, distorted, and raw feeling.

In general, the goal here was to have things loud, distorted, and raw feeling. In particular, for the idle for this set, I wound up going very low tech for it – using recordings of a leaf blower on low speed, and some very faint fireplace crackling recordings that Mark had done ages ago. With a bit of EQ, compression, and distortion, it just felt right in game.

DS: Ship engines were a blast to work on. We were given a lot of creative liberty. We basically divided the work so that each ship manufacturer had a sound designer. Mark sort of paved the way. There is a lot of real-world grounded content and recordings utilized for ships – “NASA punk” as Istvan Pely coined so well. In addition, there’s fun and satisfying sound design sizzle for entering and exiting boost.

We were given a lot of creative liberty. We basically divided the work so that each ship manufacturer had a sound designer.

RE: I worked on the Amun Dunn engines. These certainly aren’t the most high-tech-looking engines, but they do look powerful. I wanted the sound to be very rustic and deep with lots of stuttery popping. I ended up taking the sounds of a person walking in high heels, and another of a person running in tennis shoes. I processed them with enough plugins to crash my Reaper session, added some sub, and that’s pretty much it!

ML: Istvan has a set of switches on his desk which are a recreation of the old Apollo-era spacecraft toggle switches (the kind with the little guard rails on either side). It was late in the project by the time I happened to notice them in his office, and he let me borrow and record them in action, just in time to mix them into some of the knobs and switches that you hear as the player initiates a grav jump in one of the cockpit types.

Istvan has a set of switches on his desk which are a recreation of the old Apollo-era spacecraft toggle switches…

As for the engines, I made the Slayton Aerospace set, and there are two key elements that I remember using: the first is a really intense whine from a zipline that I rode on during a trip with my family to Costa Rica a few years ago. I was able to put a small recorder in the zipper pocket of my hiking pants, and with the long run of the zipline that we were riding, the wheels of the trolley mechanism were just screaming as you hit your top speed. Because of that intensity, plus wind noise, the original recording is a bit blown out and distorted, but it all still works when mixed in with other elements of the Slayton engines’ boost sound.

…he let me borrow and record them in action, just in time to mix them into some of the knobs and switches that you hear…

The other element that can be heard in the interior cockpit view as you push the throttle hard is the whine and vibration heard in the cabin of a 737 aircraft as recorded by a discrete pair of binaural mics that I wore for takeoff and landing on a few flights.

CCz: For one of the specific ships the player can get later in the game, I’m using some fire rumble and other sound effects from libraries, but amongst those layers, I have some tonal drones I recorded on a Korg Minilogue, cymbal swells that Mark recorded, and a layer of brass orchestral chaos that was recorded during the score’s live orchestra tracking sessions. All of this varies in intensity depending on the player’s speed.

Your ship is your home essentially, so how did you use sound to make it feel like home?

RE: With shipbuilding, the player can piece together any number of various ‘hab’ types from several different manufacturers. Each manufacturer has its own distinct brand. For example, Stroud-Eklund is very sleek, modern, and comfortable, whereas HopeTech is known for its large, often ugly freighters and cargo vessels. I wanted the different brands to be sonically different. So if you bought the HopeTech habs you would get more rugged, rattly-sounding ship interiors; if you went with a company like Stroud-Eklund you would get interiors that sounded more modern and clean sounding.

Aside from the roomtones, each hab has soft little sounds that play from all the machines, terminals, pipes, vents, generators, fans, etc. to make the ships feel more lived in.

Each manufacturer makes a lot of different hab types: mess halls, control centers, engineering rooms, med bays, crew quarters, captain’s quarters, etc. The roomtones for each of the habs have two layers of audio. The first layer represents the manufacturer and is consistent across all the various hab types made by that manufacturer. The second layer is completely unique to match what’s in that hab. This helps to give a consistent sonic identity to the various habs that each manufacturer makes, while allowing them each to be completely unique.

Aside from the roomtones, each hab has soft little sounds that play from all the machines, terminals, pipes, vents, generators, fans, etc. to make the ships feel more lived in. The attenuations on all the soft little sounds are kept pretty tight to make the space feel intimate as you walk through the different parts of your ship.

What went into the sound of weapons and hand-to-hand combat?

ML: It’s taken me many years and several projects, but I’ve finally started to feel confident about making satisfying weapons fire sounds, finding a reasonably reliable method of making a gun feel good for the player, and then taking that same gun and splitting off its many modded versions.

…I push up that master just a smidge so that the gun outright distorts, even if just a fraction of a second. It ought to hurt just a little.

I like gathering up my source audio into three categories, and routing them through exclusive busses in my DAW so that each can have its own compressor: one group of sounds are all the mechanical elements like the gun’s bolt slamming back and forth, one group is the ‘bang’ or the real meat of each gunshot, and finally one group is any low-end thump or sweetener. But then I add a pure delay to each of those busses and play around with very subtle amounts of delay for each which really changes the characteristics of the shot. Moving the mechanical sounds even just 15 milliseconds before or after the bang, or having the low-end thump hit first or a while after everything else can really affect the feel. Those busses all sum out to a master fader with one more compressor. Last, but certainly not least, I push up that master just a smidge so that the gun outright distorts, even if just a fraction of a second. It ought to hurt just a little.

But more than anything to do with the source material or the various methods one uses to come up with gunshots, the gun has to feel powerful and satisfying for the player to shoot, regardless if it’s something from the real world or completely sci-fi. Getting all of that to feel good with something like an energy weapon is a challenge. Even if you’re using all kinds of synths and effects, it’s tough to beat using at least a little bit of a real cannon, a slammed heavy door, or something like that. It still has to feel powerful and dangerous.

DS: I love happy accidents in game audio. I talked about the Cutter weapon earlier, and I want to share a quick story about another weapon. There is an Arc Welder weapon in the game. I created content for it, and was auditioning it in the Wwise soundcaster. I kept hearing this great layer as part of the player fire loop. However, this content was unfamiliar. So I did some digging, and I couldn’t find content in Wwise for it. Curious! What the heck am I hearing? I was stumped, but I loved it as part of the sound of the gun. I had to figure this out.

I kept hearing this great layer as part of the player fire loop. However, this content was unfamiliar. So I did some digging, and I couldn’t find content in Wwise for it.

It turns out that the rumble data in the Wwise event was causing my Xbox controller to rumble and vibrate on the table next to me. When I pressed play, I’d hear the authored player fire in my headphones as well as the Xbox controller vibrate on the table next to me. Xbox for the win! So, I recorded it and added it as a layer for the Arc Welder.

CCz: Going along with what Mark said, we have multiple layers for the gun sounds. Typically those are the tactile mechanical sounds and the “bang” fire sound. Using those elements we have subtle audio cues that let the player know when their current ammo clip is about to run out. We’re basically counting the amount of ammo they have in their clip and when that number gets low enough, we start playing the mechanical elements louder and louder while slightly high-passing the “bang” fire sound. So the player gets a subtle cue that they need to reload while keeping them focused and interacting with the world instead of having to look down at the UI ammo count.

What went into the sound of Vasco?

CC: Vasco – and by extension the other “Model A” robots – was a blend of efforts. Very early on in production, Chris Hite worked up some of the more chirpy/musical non-vocal sounds they make, and those are still in use to this day. Also, the vocal processing for Vasco is one Mark tackled and can speak better to.

All the other elements – the heft, weight, and movement of these bots – are something I tackled with a mixture of things like heavy metal impacts (metal junk, or appliances being smashed and slammed with various implements), car door/trunk slams, and various kick drum samples for low end for the various types of “steps” that they can take. Other movement elements pulled from things like pistons and pneumatic devices.

Very early on in production, Chris Hite worked up some of the more chirpy/musical non-vocal sounds they make, and those are still in use to this day.

The other subtler details (when they rotate their chassis) were made with a blend of some of the aforementioned pneumatics, some library recordings of window blinds being raised/lowered, and some recordings of a Sentry Bot one of our artists made years ago.

From there, the different “Model A” frame types had content added or removed to make the Heavier or Skinnier framed versions of them feel different. When you come across the Medic or Farmer Model A types, you can notice they’re far less weighty feeling, using much thinner and flimsier metal sounds, locker doors, filing cabinet drawers, etc.

ML: I’ll say this for the vocal sound of any robotic character (assuming, of course, you want the character to clearly have a robotic quality), the voice actor is really going to lend the most creative piece of the puzzle. That is, you decide what the robot should sound like and then just let them perform it!

I’ll say this for the vocal sound of any robotic character…the voice actor is really going to lend the most creative piece of the puzzle.

After that, any additional effects processing elements I add are really just the final coat of paint, something to bring it all together. The real character comes much more from the vocal artist’s performance than any knob I could turn to instantly produce a robotic voice, particularly if you want it to still be intelligible by the listener.

Vasco’s voice actor Jake Green had read some computerized voices for us in previous games, and he has a very crisp and clean vocal style, a clear pacing and enunciation that stands up well to any effects processing we might use. The key was to let him play with the vocal delivery and find that slight halting and pausing with which Vasco speaks, as if his processors are crunching for a moment and assembling the correct phrasing.

The key was to let him play with the vocal delivery and find that slight halting and pausing with which Vasco speaks…

Prior to Jake taking the role, I had done some temporary reads for Vasco in early testing and found some success in doing what I call the “BBC cadence.” There’s a very particular way that announcers for the BBC speak which uses those careful pauses, and they’re not reading completely flat; there’s still a little bit of pitch dynamics in there, but they’re also not getting too excited. So I would do that but then just use my normal American accent. I made some guide recordings of that, sent them over to the studio where Jake was recording, and then he took that and filtered it through his own interpretation.

After all of that, the effects processing almost isn’t even worth mentioning. It’s really just getting some very light pitch and formant adjustment through Ircam TRAX, then a band-pass EQ, and finally getting squashed and evened out through a compressor/limiter. But it really does come down to the original read by a real human actor. The same is true for Wes Johnson’s ‘Protectron’ robot from our Fallout games; it’s really the actor giving that robot its unique sound. I don’t have any “make it funny” plugins that would work the way an actor can when they interject just the right pause at the right time, or add that light touch of sarcasm to poke fun at the player.

What went into the sound of the player’s foley? Since you’re in a spacesuit, how did that affect the foley? Did you did filter the foley sounds to give that ‘suit’ feel?

CC: Separating out foley from movement/footsteps sounds was a first for us in Starfield. We wanted to support more granularity in movement based on which surfaces the player is interacting with, their movement type/speed, and also what they are wearing.

We wanted to support more granularity in movement based on which surfaces the player is interacting with, their movement type/speed, and also what they are wearing.

We support 3 types of outfits, and 3 classes of spacesuits. For the suits themselves, each is a bit heftier than the last: lots of heavy cloth, vinyl, and occasional rubber elements for each, with things like different packs, straps, buckles, and other jingly elements layered in for each set.

As for filtering, there is a bit of filtering and attenuation over distance that happens in real-time with Wwise based on the player’s camera perspective. But outside of that, the content was authored to nestle in the mix without any filtering at the DAW level.

What were some of your biggest technical challenges in terms of sound for Starfield? What were the solutions?

FT: Creatures were challenging. It was a lot of trial-and-test, especially when we started working on them while the transition to Wwise was happening. There are hundreds of creature types in this game, sharing the same animations, and it was clear from the start that they would not all have unique sounds. We ended up making four sound sets per creature type, while also modifying the sound based on the size of every creature. Unique creatures (like the Terrormorph) were simpler to work on.

There are hundreds of creature types in this game, sharing the same animations, and it was clear from the start that they would not all have unique sounds.

DS: What wasn’t a technical challenge? We had crowd walla, ambiences, vehicles, and ship modularity. Not to mention that this game is enormous. Because of the procedural nature of the game, we had to figure out a procedural ambience system. There were huge challenges to overcome, and it all came together.

JS: Sound design for creatures was an interesting challenge since there are so many in the game.

Creatures in Starfield are constructed from a large library of modular components and assembled into hundreds of unique combinations at runtime. While a quadruped creature in a desert environment may have large horns and bony armor, another in a jungle environment may be more lizard-like and covered in reptile skin. One may be small, fast, and aggressive, while another may be large, timid, and quick to flee from danger.

Vocalizations and attack sounds are further categorized into multiple sets of sounds per creature family.

To efficiently create sounds for such a large number of creatures, we also chose to design a modular system. Footsteps, movement, and impact sounds are assembled from a library of material-specific content that is selected based on a creature’s size and visual characteristics.

Vocalizations and attack sounds are further categorized into multiple sets of sounds per creature family. Although creatures share the same basic animation data (attack, howl, fidget, etc.), this system allows us to assign a unique voice based on specific gameplay criteria. This gives us the ability, for example, to easily make a jungle quadruped roar or screech different than a desert quadruped, or make an aggressive creature sound more threatening than a passive one.

CC: One challenge was the point where voiceover collides with things like helmets and ships, haha. We needed to be able to support an NPC speaking a line right in your face (without a helmet), or while wearing one of 8 or so different helmets, or firing off a line on your ship, or from a remote ship. It was important to me to be able to distinguish, on some level, between all of these. For example, when NPCs on your ship speak to you, they sound a bit clearer, less distorted, and bandpassed.

…runtime when each line of VO is fired, the game data, code, and Wwise data route things to the appropriate real-time effects configured in Wwise…

However, when an NPC is speaking to you from another ship, I wanted to convey a bit more signal degradation, so I added more distortion, filtering, and noise to the signal. All of this happened with a system of switches, states, and associated effects chains in Wwise in conjunction with game data and code our Audio Programmers Jason Hammett and Josh Martel tackled for us.

The end result ensures that at runtime when each line of VO is fired, the game data, code, and Wwise data route things to the appropriate real-time effects configured in Wwise to deliver the right feel for each line.

What were some of your biggest creative challenges for Starfield?

FT: We needed both the Terrormorph and the Heat Leech to sound menacing. Jerry did most of the terrorizing sounds of the Terrormorph based on recordings he did of a yoga ball being slowly rubbed. I ended up using the same source material as him for the Heat Leech and processed it differently; this way both creatures would share the same family of sounds.

DS: *SPOILER ALERT* If you’re reading this and haven’t explored the main quest, there will be spoilers in my answer. I’ll still try to keep it as general as possible. Spoilers: There are special abilities that the player can acquire. These were tricky to nail down. I love doing work related to special abilities. This was some of my favorite content to work on in Skyrim. Throughout Starfield, it was challenging to envision and then implement great audio for special abilities and all of the fun moments they entail. There’s a story to be told with each ability. What story did I want to tell with sound for these abilities? They also relate to some of the deeper mysteries in the game. So there was always that in mind as I approached the content.

Sometimes the audio approach was obvious, and sometimes it was more challenging. I believe one of the earliest abilities the player can acquire is the Personal Atmosphere ability. This is probably my favorite content I authored for abilities. From the name, you have some expectation that this ability does something with air and the atmosphere. Before I even begin designing anything, the name and context set expectations. It’s important that the audio conveys an experience in line with that expectation. If you hear this audio by itself, can you guess that it somehow manipulates air? It’s a similar story for many other pieces of content like that throughout the game. There are many more surprises for players to discover themselves. So I’ll leave it there.

CC: *SPOILER ALERT* In terms of the voice processing effects for the Starborn NPCs, we really wanted these characters to stick out and feel otherworldly, somewhat magical, but also technologically sophisticated in a grounded and real way that felt like they could have come from a similar origin as us. For the Starborn character “The Hunter,” I took a mixture of the voice actor’s performance, ReaPitch in Reaper for pitch layering, various FabFilter Pro-Q 3ing and compressions, NI’s Flair and Choral plugins, Audio Ease’s Speakerphone, and a handful of other plugins blended together with Zynaptiq Morph and a layer of in-game music of the Artifacts “beckon” music that you hear when you’re close to them in-game. The idea was to try to infuse the character with some element of the Artifacts themselves. Doing this gives the character a dark and sinister feeling, with a healthy bit of grit. If you really listen to some lines, you can even hear bits of the Artifact singing as he speaks.

ML: There were two big items that I simply had to iterate on for a long time, and that’s the sound of the ship creaking and groaning around the player as they step on the gas or jerk the controls about, and also for what I’ll call the “rings puzzle” so as not to give away any spoilers here.

Our coders were able to pass us the calculated G-force values on the ship for that acceleration and deceleration…allowing me to use two different sound sets for those different groups of forces.

Sometimes it’s a real pain when you know exactly how you want something to sound before you even start on it because you’re going to spend a ton of time trying to reach that perfect thing that you hear in your head. Early in the project, I felt certain that I wanted the ship piloting experience to feel very realistic when in first-person view inside the cockpit. I played a lot of flight simulators growing up so I really like a sense of realism. I love the sound design in the 1981 Wolfgang Petersen film Das Boot, so being in a submarine became my analogy for the sound of being in a ship in space. Even if it’s a vacuum outside of your ship, I figured inside you’d still hear the stresses pulling on the ship around you as you accelerate rapidly or pull high Gs when turning at speed.

Our coders were able to pass us the calculated G-force values on the ship for that acceleration and deceleration, and then similar values as you roll, pitch and yaw, allowing me to use two different sound sets for those different groups of forces.

That sound content also switches depending on what cockpit “make” you’re flying in. Stroud ships are fairly well muted and insulated, whereas the more industrial Hopetech cockpits really rattle and strain around you (making them my favorite for that very reason). It all switches off the type of cockpit you have installed on the ship.

Creative work doesn’t necessarily need to be efficient or elegant. Sometimes you just have to keep showing up and go through all the bad ideas so that you can get to the good one(s).

Getting all of that feeling just right simply took a ton of iteration. I returned to the same project so many times, trying it this way and that, switching out content, making it more aggressive one day and less aggressive the next. Creative work doesn’t necessarily need to be efficient or elegant. Sometimes you just have to keep showing up and go through all the bad ideas so that you can get to the good one(s).

Without saying too much about it, the “rings puzzle” uses a lot of the live orchestra that performed much of the game’s soundtrack, blending between the orchestra intentionally playing a kind of musical chaos and then through that very sonorous sound of tuning up together, and finally to the big, bright major chord of the game’s main theme. In the midst of that is mixed in a 20-inch ride cymbal that I have, playing tremolos along its edge with mallets and then blending again through different dynamics, from low gong-like rumbles and throbs to a bright, shimmering wash. It’s almost too loud as you really push it to that final intensity which I like. I wanted it to approach unbearable, like staring into a bright light.

Starfield uses Bethesda’s Creation Engine 2. What impact does that have on the sound team? Did you use middleware?

CC: This is the first Bethesda Game Studios game to use Audiokinetic Wwise, which we switched to midway through development.

The biggest challenge we had initially was trying to support both the old, proprietary audio tools, and Wwise simultaneously. One of the biggest wins for us here was being able to really flex a lot of the real-time processing capabilities for things like VO. Roughly 70% of the VO in-game is processed in real-time now, as opposed to offline. This saved us a ton of time at the end of production, especially where localized VO was concerned!

…we transitioned away from our long-serving and homegrown audio tools and switched over to Audiokinetic Wwise, right smack in the middle of the project!

ML: Stepping back and looking at the lifetime of the whole project, far and away the biggest challenge was that we transitioned away from our long-serving and homegrown audio tools and switched over to Audiokinetic Wwise, right smack in the middle of the project! I was hesitant to make the move as it was a big risk to take, and I really credit the team for pushing to make the move (and especially our audio coder Jason Hammett for pulling it off so seamlessly).

Our proprietary audio codebase had carried our work through many successful projects, but for all of the new types of gameplay that Starfield introduces, it just wouldn’t be able to keep up with everything we’d need to do.

So, the great migration began, and Jason very carefully worked on bringing each aspect of our games’ audio over one piece at a time. I’ll say that the larger development team never really noticed that this big change was taking place; nothing ever broke and gave away that he was ripping the audio guts out of the game and replacing them.

It wasn’t that long until I was really starting to get a feel for the creative power we had with the new tools…

Then there’s the not-small matter of learning and adjusting to working in a new environment, and here I just really learned a lot from the rest of the sound team as many of them had much more experience with Wwise than I did. It wasn’t that long until I was really starting to get a feel for the creative power we had with the new tools, and with the game being so large and the project so long, there was still plenty of time to really leverage Wwise’s power and ease-of-use. It’s hard to imagine how else we’d have properly handled systems like the ship engines and cockpit shaking, not to mention the complexity of some of the game’s quests and locations.

It’s strange now to think that we started this project working in one toolset and then finished it completely in another. If it were possible to take our old, homegrown audio engine and put it in the trophy case here at the studio, I’d do so – that code helped deliver a lot of memorable and beloved games for our fans and in a lot of ways probably influenced the signature sound of a Bethesda Game Studios roleplaying game. Even if we’ve moved on to more advanced tools out of necessity, it still deserves a salute.

How has working on Starfield helped you to grow at your sound craft?

FT: Everyone was able to work on many different aspects of the game, and I think we all were able to work on things we didn’t work on before. I had very little experience with guns before, and I never expected to work on a melancholic sanitation robot one day. So, these were a nice learning experience.

DS: Audio, games, and tech are some of my favorite things in the world, and working on these things every day is really what helps anyone grow in game development and game audio. Every Bethesda game I’ve worked on has been a tremendous workout of every audio and tech-related muscle group you could think of. We’re a relatively small team and we were all able to dig into just about everything in the game. Game development is very much a team sport. This project was a tremendous opportunity, and I couldn’t be more proud of the audio team, Bethesda, and Xbox.

We’re a relatively small team and we were all able to dig into just about everything in the game.

CC: As Fred mentioned, we were working on nearly all aspects of the game. We all had a few things we were the go-to person for, but just about all of us touched a bit of everything. As a result, having to consider the entire puzzle at once definitely helped me dial in a unified feeling for how each element should sound, not only in isolation but more importantly how to fit as part of the whole.

ML: More than anything, I think it’s my overall methods that have improved, meaning the way I approach creative work or intuitions about what’s going to work and what isn’t. Starfield is such an enormous game and encompasses so many different varieties of sound design that there was always something else that you could switch to if you were stuck, and that’s really the thing that I understand better now: work on something for a set period of time and don’t allow yourself to be distracted or turn away when you’re not making progress, just stick it out for however long you said you’d work on it. Then, when that time is up, save your work and turn to something else for whatever time you’ve allotted to that task. You can come back to that previous item tomorrow when your ears and brain are feeling fresh again.

One of the best things I did was to let the rest of the team take over whole chunks of the game…

This is especially true with weapons fire – work on it a little bit at a time but then put it down! When you come back to it you’ll instantly know exactly what it needs, or even what it doesn’t need (that is to say, what to remove). That’s something I’ve done a lot: pounded my head against some project for a long time and used up all these tracks and effects all over the place, and then the next morning threw out eighty percent of it and came up with something better in about five minutes. It’s like saying your own name over and over and how it quickly loses all meaning and just sounds like gibberish.

Another really important thing I learned over the long course of Starfield’s development is that it’s okay to just let things go. One of the best things I did was to let the rest of the team take over whole chunks of the game, like the way we split up the cities so that each one had an “owner,” and the same thing with the ship engines, the weapons, the enormous and complex creature system – all of it. Everyone got to pour a piece of themselves into each aspect of the game, and it all probably ended up much more unique and interesting than if just one person had been the weapons designer, one person the city designer, etc. It introduces a little more randomness, a little more chance, into the game’s overall sound design picture, and I like that. The in-world “diegetic” music that you hear in many of the game’s locations, like the clubs and bars, is all written by the team, and we all just went for it. It was really good to step back, let go, and even after many hundreds of hours of playtesting still thoroughly enjoy it all.

A big thanks to Mark Lampert, Casey Coffman, Dave Schreiber, Frédéric Tardif, Jerry Schroeder, Cazz Cerkez, and Richard Evans for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at the sound of Starfield and to Jennifer Walden for the interview!