Interview written by Jennifer Walden – may contain spoilers

Director Adam Wingard’s take on Death Note is now playing on Netflix. The film, based on the popular manga series written by Tsugumi Ohba, follows a student named Light Turner [Nat Wolff] who finds a book wherein any name written will cause that person to die. The book belongs to a mischievous death god name Ryuk [voiced by Willem Defoe]. Light and his girlfriend Mia Sutton [Margaret Qualley] try to use the notebook for good by killing off criminals but soon run into trouble when a special agent named ‘L’ [Lakeith Stanfield] hunts them down.

For post sound, Wingard returned to Technicolor at Paramount where he worked with Emmy-winning supervising sound editor/sound designer Jeffrey A. Pitts and supervising sound editor/ re-recording mixer Andy Hay — a sound duo that worked with Wingard on Blair Witch last year. Hay (dialogue/music) and Oscar-winning re-recording mixer Gregg Rudloff (sound effects/Foley/backgrounds) final mixed Death Note on Stage 2 at Technicolor. In addition to a theatrical 7.1 mix, they also did a 7.1.4 Home Atmos mix and a 5.1 mix.

You’re back again with Dir. Adam Wingard. What were his ambitions for sound on Death Note? How did he plan to use sound to help tell this story?

Jeffrey Pitts (JP): He’s pretty open to exploration so early on he told us to do whatever we wanted to do, and then we’d meet and trim it down and shape the sound. So that was the initial pass because we’ve worked together so many times now that everyone knows everyone. We all know what each other likes.

Andy Hay (AH): We end up shaping the soundtrack all the way down to the print master. The process that Adam [Wingard] considers to be sound design isn’t just something that happens in editorial. We are constantly bouncing the ball and playing the game all the way down to the last day of the mix. The way that we work allows us to be collaborative like that. Adam is present every day of the mix. He likes to be there and hang out, no matter if we’re pre-dubbing Foley or actually putting together a scene. So he’s ever present and that’s just also part of our process.

In an interview, Wingard mentioned the soundtrack has an ‘80s influence. How did that ‘80s influence relate to the sound design?

JP: With the ‘80s music, there’s so much space in it that you can add a lot more sound in there than you could a symphonic score that is very wide and thick. Having the ‘80s music was really helpful. For example, during the foot chase scene, with the ‘80s music there was room to poke sound through the mix that you wouldn’t get to do normally. So that’s where that type of score influences the sound design — basically, you can add more of it.

The synthetic nature of the score also sets a definite tone; it creates a framework for the rest of the sound design to sit in

AH: The synthetic nature of the score also sets a definite tone; it creates a framework for the rest of the sound design to sit in. I think that works really well from a sound design perspective because you’re already playing in a space that is using synthetic elements so otherworldly sounds fit in. If it was an orchestral score then it’s harder to work in interesting and creative new synthetic sounds.

JP: Synthetic with synthetic will pretty much work. Synthetic sound design with a lot of brass and woodwinds that’s harder to make it sound right. It doesn’t play so well.

[tweet_box]Behind the detailed, synthetic sound of ‘Death Note’ – with Jeffrey Pitts and Andy Hay[/tweet_box]

How were you able to use sound to pull the audience in? Is there a particular scene or example you’d to like share?

JP: The sound during the montage sequence in the library, where Light and Mia are talking about all the things they want to do as Kira, that was great. There were a lot of slow motion shots of people. I think we pulled the audience in with that. There was really cool score in there. I’m such a sucker for that detuned pad sound. So that was nice. You get a feeling from what that score was doing and we were able to add some really cool sound design to go along with it, to keep the pace going and to add some elements in there that people might not recognize but they’re definitely story points. I bet if someone watched it 15 times they might start picking up on some of that stuff.

Video feature on the sound for Death Note

There’s a scene when Light is reading the Note at home and he finds the page about not trusting Ryuk. The lights go out as a train passes, but what grabbed me was that long, long door creak. Can you talk about the sound there? What went into the design?

JP: There was a studio that I worked at years ago in Santa Monica. The machine room for Studio C had this half-door thing with weird hinges. It had 100 little hinges that ran down the side of it and that’s what it sounded like. As long as you wanted a creak to be, you could move that door and it would creak the entire time. You could slow it down or speed it up and it would creak non-stop. So I recorded this door every which way possible. It’s not a sound that you can use all the time, but it’s definitely nice to have that in your pocket. Those long creak sounds are difficult to come by.

You always have to keep your ear out for interesting sounds and capture it. Don’t wait to capture it. And then make sure to put some metadata on the file so you can find it later. That’s the most important thing.

You always have to keep your ear out for interesting sounds and capture it. Don’t wait to capture it. And then make sure to put some metadata on the file so you can find it later. That’s the most important thing. I captured that sound with a Sony PCM-D50. At the time, that is what I had. It was what I used to capture everything. It’s better to get a sound with a Sony D50 than to try to wait until you own some Sanken mics or Sennheisers. You should just get the sounds when you can with what you have.

AH: And then fix it in the mix!

JP: Once you put it in the mix behind other sounds you won’t know. It’s going to sound great. It’s not a big deal. Looping material to create a long door creak is challenging because you end up with loop points. There are some tricks to doing that but it’s better to just have the material.

There were other great opportunities for sound on that scene. Anything else you wanted to talk about in particular?

AH: We played a lot with the train elements on the stage. In the scene before this one, we just had the train go by as Light and his father are in the kitchen eating dinner. So since we had already introduced that element, we wanted to give an arc to the one in Light’s room. It starts out very literal but then it shifts to become part of introducing the supernatural and then it leads us out gracefully to the long door creak and the introduction of Ryuk.

In the mix, we messed around with it, finding different parts of it that we wanted to highlight more. We put a ton of bass in the rear speakers in the surrounds to shake you from the back.

JP: That sound in particular was another example of finding a sound and just recording it. I was in my condo in the Valley and they were stripping the street outside. If you’ve never heard that, the sound just vibrates your entire place. Things are shaking and vibrating. I set up a holophone (which captures surround sound) in my dining room to capture these machines going up and down the street and just vibrating my place like crazy.

I set up a holophone (which captures surround sound) in my dining room to capture these machines going up and down the street and just vibrating my place like crazy

It’s like being a chef. You want the right ingredients that you can just drop in. Having that sound and knowing that I had it gave me an opportunity to showcase it.

AH: So that’s what we ended up throwing in the rears — that sound that Jeff recorded of the street muncher.

JP: It had a really cool harmonic to it. It wasn’t just low-end. It has this really fast harmonic content that was kind of woody that was perfect for that scene.

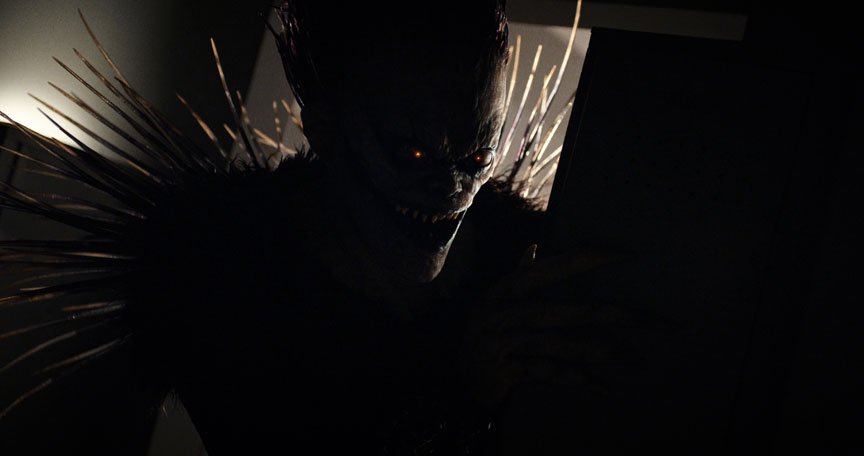

Tell me about Ryuk. What went into his sound?

AH: Adam [Wingard] and I talked about him pretty early on; I think it was day one of our post production meeting where everyone met each other across all departments. It was one of those things that was on my mind since learning about the project. I had watched the anime and was a fan of that. I had read the scripts for this film. Ryuk is more meddling and menacing in this film than he was in the anime. He comes off as a slightly different kind of character.

So I talked to Adam about how he wanted the audience to perceive Ryuk. How godlike is he? Is he in the scene with Light? Is he part of the natural world? Or, when is he part of the supernatural world? Ryuk actually shifts his presence throughout the film. Sometimes he is playing in the scene naturally with another character, sometimes not. We learn early on that the keeper of the book is the only person that can see him. We see Ryuk because Light can but no one else sees him. There are these differences in the perception of him — as far as how he sits in the picture and we had to wrestle with those.

But as far as what we did to him sonically, it wasn’t that much. 99% of Ryuk’s sound is just Willem Dafoe being a bad ass, stepping up to the mic and just delivering. We did a bunch of recording over at FOX Studios, which was amazing. He came in for a few sessions and we tried out different mics on him. He was wearing all of this head tracking gear because we had to get all the motion-capture in order to superimpose his face onto the practical character with visual effects. So not only is he learning the character in a post process (because he wasn’t on-set) by doing his performance ADR style, but he’s also wearing this 20-pound helmet with cameras and lights shooting into his face the whole time. He was just a trooper. He spent eight hours doing that in the first session and he just nailed it. He found the character and just went for it.

99% of what you hear from Ryuk is just Willem Dafoe

For us, in terms of processing, there’s no trickery. There’s no pitch shifting, or warping, or anything like that. There is some EQ and dynamics processing, some reverbs and tricky panning in some areas, but 99% of what you hear from Ryuk is just Willem Dafoe.

JP: The Foley really helped a lot. We spent a lot of time making sure his quills sounded correct and his leather. The Foley team at Happy Feet Foley is great. They’re used to doing projects like Game of Thrones, which has really rich, creaky, leathery stuff. So that all came together really well.

I did take some of Willem Dafoe’s voice work and added that into the design in some places, so that material was effected a lot obviously. I don’t want to point out any particular spots because I don’t want to give away what was derived from his voice and what wasn’t. The sound is in there though.

Sometimes there’s a low growling sound when Ryuk is around. What went into that sound?

I spent about $100 on all this handmade Japanese paper. I brought all of that paper into the studio and recorded it every which way possible. I tore it, flapped it, drew a violin bow across it…

JP: There’s a little paper shop in Santa Monica that specializes in Japanese paper. I went down there early on, before I even saw a lick of film. I don’t even think they had started filming it yet. I spent about $100 on all this handmade Japanese paper. I brought all of that paper into the studio and recorded it every which way possible. I tore it, flapped it, drew a violin blow across it… Handmade paper is very textured. There’s a lot of stuff in it. So I came up with a lot of rich sounds that I was able to pitch down. That growl was literally one of the strings on the bow that had broken off, just that one piece of hair scraping across the paper. I had this giant piece of paper that was 3’ ft. wide and it was rolled up so that it has this cavernous sound to it. I had a Sennheiser 8020 stuck into it and I had a contact mic on it. So this scraping sound, when I pitched it down, turned into this really growly sound.

Jeff, you went to Japan to capture sounds for Death Note. Can you tell me about your trip?

JP: The cool thing about Adam is I can tell him I want to go and do this thing, and he says, “Ok, go do it.” I told him I wanted to go to Japan and record Japanese backgrounds to use in the soundscape for Seattle. I wanted to introduce these backgrounds for Tokyo into the sound of Seattle’s as a call back to the original series, a call back to Japan.

So I went to Japan and recorded. I ultimately came up with ten hours of recorded material that I could use. Most of it is just cityscapes. But every city sounds different. New York City sounds like its own thing compared to Boston or Washington DC. Tokyo had its own sound. It has its own things.

The train-bys that go past Light’s house, I layered the Tokyo subway sounds into that. The Tokyo subway goes above ground and underground and so I found an area where I could be above the trains. There were six tracks below me and the trains were coming by pretty regularly. So I set up there and just recorded these Tokyo subway trains going by and I used those layered into the train sound for Light’s house. The train in the film needed to be bigger than life. You couldn’t just use the Tokyo subway car for it but the sounds I recorded had great clacking. So the clacks for the subway cars worked out really well.

There are a number of really beautiful wide shots of Seattle and I was able to take weird textured traffic bys that I got in Tokyo and warp those a bit to create interesting sound reprieves.

I wanted to travel light so I brought a Sound Devices 702 and two Sennheiser 8020s. If I were to do it again, I would’ve brought my contact mic because it wouldn’t have weighed me down but I would have been able to capture the doors in the Airbnb that I stayed in. They had these really cool sounding sliding doors. I recorded them but the contact mic would’ve given me a great sound. So that’s one thing I wish I would’ve brought with me.

When I recorded in Seattle, I brought all of my gear. You can get weighed down pretty heavily and I didn’t want to take all of that to Japan. It’s better to travel light.

What was your favorite scene to work on? Why? What went into the sound?

JP: I would say the Ferris wheel scene. Cutting design for me feels very natural; it just comes out, but cutting action is fun for me because it’s like a different part of my brain that’s working. I feel like I am almost composing something that has beats. So that was a really interesting scene to work on for me.

[I]f you ever need to record anything outside in a quiet environment go to the Mojave Desert. If you get there at the right time, there are no insects, birdlife, or anything. … There’s no wind. Nothing. You just hit record.

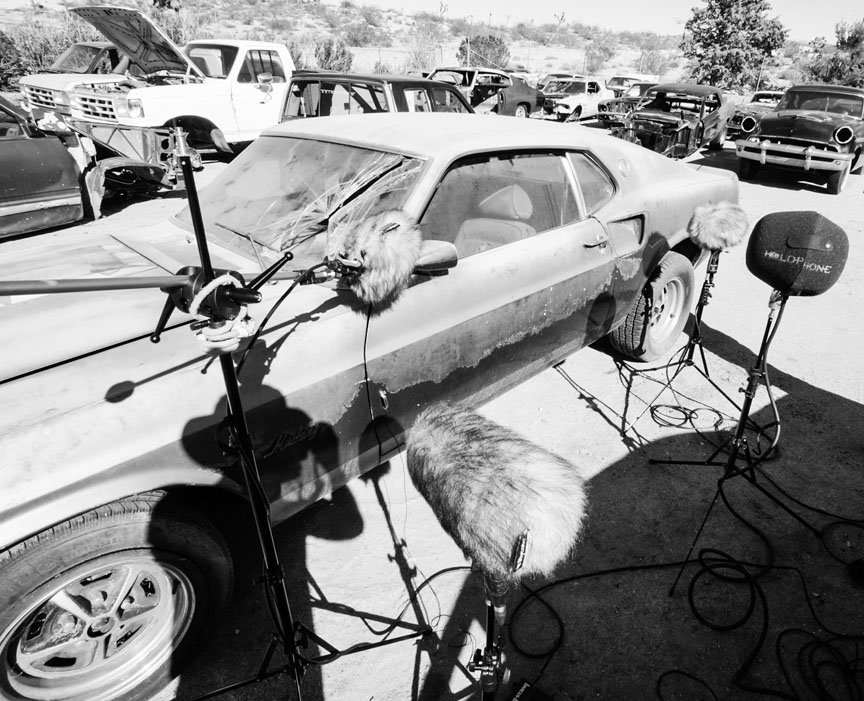

Andy, my friend, and I went out to a junk yard in the Mojave Desert. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to the Mojave Desert, but if you ever need to record anything outside in a quiet environment go to the Mojave Desert. If you get there at the right time, there are no insects, birdlife, or anything. You feel like you’re in a three million-dollar studio. There’s no wind. Nothing. You just hit record.

I knew how quiet it is from past recording sessions and that we needed to find a junkyard out there. I wanted to get a bunch of new metal sounds, a bunch of new creaking and wonking for the Ferris wheel. So we found a junkyard that had all of these old Mustangs. It was a Mustang graveyard. It was the coolest place. We recorded all of these car doors that hadn’t been opened for 30 years or something like that. We recorded weird trunks that weren’t even trunks anymore. The top part of the trunk was there, but the rest of the car is gone. You get some really weird noises. We got really crazy sounds from a couple pieces.

So we set up all of our equipment on this one door that we figured hadn’t been opened for 30 years and we wanted to get that first sound. So we set up all of our mics, including a holophone, two Sennheiser 8020s, a RSM 191… we set all of these up and then we go and open the door and it didn’t make any noise! So from then on we walked around and opened some doors to make sure they made noise before we went and recorded them.

We got some incredible sounds from there though. There was half of a truck, basically just the cab of the truck, and we were able to push it around because it really wasn’t that heavy. So we were sliding it around and recording these cool, heavy metal slides.

AH: We came across a windshield that was cracked and broken, and looked like it had some dried blood trickling down it. It looked like something had happened there. That windshield was made from regular glass, before they had safety glass!

JP: That was fun to work on the Ferris Wheel section, from collecting sounds for it all the way through to editing it and then watching it all come together because that sequence was all green screen and CGI. Watching the whole thing come about was interesting.

AH: Watching it all come together on the mix stage was fun too because we had so much sound material and so much score. As is typical, each separate department is working on the film and cutting simultaneously and it’s not until the mix phase that you realize all the material you have on hand. So for any given scene, I would take a pass on mixing the score first. I had tons and tons of stems and that was great because it gave me flexibility and the ability to remix on-the-fly as needed.

I would go through this whole five minute scene and realize that I could play just the score and it would be incredible but then I have all of the effects too. So you get into the dance of it. We had Gregg Rudloff doing our sound effects mixing and he was amazing. He’s an Oscar winner for Mad Max and some other films. He just had this incredible ability to shape scenes to make the right things play. He brought a real elegance to what I call the dance of the mix. He was a huge asset to pulling off the sound of this film.

What was the most challenging scene for sound?

AH: Maybe that classroom scene with Ryuk where everything was flying around. That was pretty tough.

That was tough because you had to have a chaos about it. But then there were these specific sounds that needed to poke out as well. It was a real challenge to get everything balanced and set up right.

JP: That was tough because you had to have a chaos about it. But then there were these specific sounds that needed to poke out as well. It was a real challenge to get everything balanced and set up right. But it was fun too, for example, those marble bys. In the production office, I recorded a bunch of marbles rolling by the mics. I had a contact mic on the cement and was getting great stuff from it.

Once you get into the chaos of the scene, it was a lot of material. All of the paper flaps in that scene came from that Japanese paper that I purchased. I had bought five or six different types of paper and recorded the sound of them flapping.

AH: On that scene, in terms of dialogue, we ended up taking the approach that if this is so chaotic and supernatural in nature then Light would be in a sense overwhelmed. So we ended up taking his dialogue down quite a bit but then it felt weird, like there was this drop in energy from him. So then we had to bring him back up but find that space where we can believe both ends of the stick. It’s so intense that he is being overcrowded but at the same time he’s still very much present. We want to feel his angst in this madness.

Another challenge was to get it to feel like the chaos was largely wind driven. Getting wind to play and not just be a bunch of white noise was definitely a challenge …

Another challenge was to get it to feel like the chaos was largely wind driven. Getting wind to play and not just be a bunch of white noise was definitely a challenge, especially when you are thickening the sound up with other elements like paper and explosions and the chairs and tables slamming around. It wasn’t anything that any of us had ever done before. We had no point of reference from another movie we had worked on. We hadn’t made something like this before. This was new to all of us and it took us a minute to figure it out.

JP: The trick with wind is that you have to keep it moving around. You can’t have any static winds. The one exception would be when ‘L’ was getting on the plane headed to Seattle. That was a steady, brash wind sound but it was quick. It was fast, not like the classroom scene where you need the wind to move and you have to tailor all of these other sounds happening as well.

The home for boys where ‘L’ was trained, that’s one creepy place. Can you tell me about some sound design highlights for you there?

JP: My first pass on that house was to make it sound old and creaky and then Adam said, “You can make it supernatural. Go really far out there.” So the floodgates opened and I was able to add a lot of crazy, spooky sound design. I got to play with that. I recorded the music box sound about two years ago, and I pitched those sounds down really low. I got to add all those ghostly voices.

It sounded like you had a lot of fun with the mix there too. You have a lot of breaths ping-ponging around…

JP: I printed those. I wanted it to be like you walked into that space and felt it. That was the space where those kids were trapped for three months. That was their trial space. I wanted it to be like as you moved into the space the sound swam around you, and then it pulled back out again. So there were a lot of ping-pong delays in there.

From a sound standpoint, what are you most proud of on Death Note?

JP: I’m proud of the whole thing.

AH: Yeah, me too. I think, for me, it was the ultimate vehicle to really take time and care and detail and love and resources and put everything into this film because of the way that the scheduling ended up working out. The amount of time that we were on it and the resources that we had available to us at Technicolor, including our staff, made it the perfect opportunity to exercise all of our muscles. For me, I think it’s some of my best work. I’m really proud of it and glad to have the opportunity to work on it. I’m proud of the whole damn thing.

JP: Yeah, I concur.

A big thanks to Jeffrey Pitts and Andy Hay for giving us a look at the creepy yet lovingly detailed sound of Death Note – and to Jennifer Walden for conducting the interview!