Building on the sonic achievements of Ghost of Tsushima, the sound team at Sucker Punch — led by Audio Director Rev. Dr. Bradley D. Meyer — approached Ghost of Yōtei from a standpoint of efficiency. Knowing they’d need to do more in terms of combat and weaponry, wanting more detailed foley, working with new story-driven elements like Atsu’s shamisen and her wolf companion, and choosing to deliver a more consistent mix meant addressing these big-ticket challenges early on by building new systems and tools that would allow them to work smarter and be more productive. hello

Here, Meyer, Josh Lord (Sucker Punch Senior Staff Sound Designer), Chris Walasek (Sucker Punch Sound Designer), Adam Lidbetter (PlayStation Studios Senior Sound Design Supervisor), and Pete Reed (PlayStation Studios Senior Sound Designer) talk about how they crafted a captivating, cohesive sound for Ghost of Yōtei, like recording unstructured prop performances on the foley stage to simulate the randomness of real life, capturing samples from instruments and performers on the Scoring Stage to use as source material for the UI sound design, building custom tools like Sound Sensei to make global changes more predictable and easier to manage, and creating a new foley system that combines the precision of linear editing with the flexibility of a modular system.

They also share details on improving combat reactions, rewarding players with combat sweeteners when using an ‘aligned’ weapon, designing audio for haptics, creating ultra-realistic soundscapes using a unique ambient sound system called Sound Scenes for locations and missions, and much, much more!

Ghost of Yōtei – Launch Trailer | PS5 Games

The sound of Ghost of Tsushima was incredible! Was there anything in your approach to that game’s sound that you wanted to carry forward to this one? Anything you learned while working on that game that helped you refine your approach to sound on Ghost of Yōtei?

Rev. Dr. Bradley D. Meyer (BDM): Ghost of Tsushima was a very special project and the team put a lot of love and effort into crafting the world. As creatives, we always want to push ourselves and make the next thing better than the last. When we started working on Ghost of Yōtei, we took some time to reexamine all aspects of our design and figure out how we could make a richer, more vibrant, more detailed world.

At the high level, the main things we knew we wanted to carry over was the deep collaboration across the team (both within the audio team and across the studio), the grounded nature of the game and its sound, and an attention to detail and fidelity across all audio systems. The Ghost games are meant to be transportive, whisking the player to our version of feudal Japan, and we do that through very careful crafting of all of our audio from ambience to foley to combat to music and dialogue.

Combat has to both feel and sound lethal. So we wanted to carry that forward, but now had the challenge of doing it for 5x as many weapons!

This was also our first game built from the ground up for PS5. On Ghost of Tsushima Director’s Cut, we designed haptics for combat, and all other systems, but this time was much more intentional design from the conception of the project.

Another high level area we wanted to carry over and improve was the attention to detail in the mix. We wanted to ensure the experience is seamless for the player from moment to moment whether that’s going between gameplay and cutscenes, dialogue and gameplay, or between different gameplay moments. We craft our mix meticulously to support the emotions we want the player to feel and it was another key aspect we took from Ghost of Tsushima and continued to evolve.

We took a good look at all of our audio systems after shipping ‘Ghost of Tsushima’, brainstormed on ways to improve them, and re-crafted a lot of our systems

At the same time, while Ghost of Tsushima sounded great, a lot of the sound design was rather static. We relied on a lot of looping sounds and events in our ambience that didn’t move around the world. Our combat impacts were a single sound played at the point of the enemy being hit. Sounds were hand-placed in missions and locations, like buildings or bridges, and always played from the same point in space. We really wanted to create a more dynamic soundscape from the perspective of being enveloped by the sounds around the player. We took a good look at all of our audio systems after shipping Ghost of Tsushima, brainstormed on ways to improve them, and re-crafted a lot of our systems to allow us to implement and iterate much quicker, while also providing a much more animated soundscape.

Because the story of Atsu, a scrappy wandering warrior, in 1603 is so much different from Jin, a samurai from a more rigid background in 1274, we also gave ourselves a bit more creative leeway in our design. The soundscape still needed to feel grounded, but we also afforded ourselves to take more risks with our design and introduce elements and layers that were more effective emotionally, but maybe were a bit more designed and less organic.

Josh Lord (JL): Combat in Ghost of Tsushima had a natural rhythm and musicality that we knew we needed to carry forward and build on for Ghost of Yōtei. The combat soundscape also carried an intense sense of physicality in every block and impact, which helped fulfill that fantasy of being in a cinematic samurai experience. The challenge was to take the core elements that worked so well in Tsushima and expand and scale them up to support all of the additional weapons that both enemies and, new with Yōtei, our hero could wield.

Adam Lidbetter (AL): Between Ghost of Tsushima and Ghost of Yōtei, we switched our audio middleware, which gave us a great opportunity to start afresh. Almost every single sound was replaced, but the approach to designing the soundscape was the same – where possible, we wanted to be grounded in historical and environmental accuracy, but to have the freedom to support the emotion and feeling of being in this beautiful and dynamic world. When you have such inspiring visuals to work with, it makes sound design quite easy in many ways!

Can you talk about designing realistic, dynamic environmental sounds for Ghost of Yōtei? Did you capture recordings of ambiences or ambisonic beds of real locations? Or, what were some sources for these sounds?

BDM: I was fortunate enough to spend a couple weeks traveling around Mount Yōtei in April of 2023 recording various wildlife and biomes. Everything was captured with a Telinga parabolic dish with an UsiPro from LOM or with a Sennheiser MKH 8060. The purpose for the recordings in Japan was to get individual species featured throughout the game so I was highly focused on capturing content we could use as point source emitters.

There is a little bit of re-use from Ghost of Tsushima, but most of the wildlife is completely new for Ghost of Yōtei, and most of it was recorded in Hokkaido.

I think the game works so well sonically due to our overlapping systems that blend in concert with each other. We have a system that plays back one shots of bird species, insects, amphibians, wind gusts, etc. procedurally based on sub-biomes around the listener; we have our wind and rain rigs and Sound Scenes mentioned below. All of those systems, coupled with our sound propagation solution for occlusion and obstruction, and some nice convolution reverbs, get everything sitting well in the world and creating this believable space.

There are no ambisonic beds in the game at all. As we’ll talk about below, we use 8-channel cube files (dual quad layers above and below) as our quads for rain and snow, but every other ambient sound is point source from wind to birds to mammals to insects to water flow (with the exception of larger waterfalls being stereo for better spread when up close).

As a grounded game set in 1603 Ezo (modern-day Hokkaido), we were pretty conservative on the amount of processing we did on these files. We did build a unique ambient sound system for locations and missions we call Sound Scenes that Josh can talk more about, and within that we built a 3-tier perspective system where we designed “near” assets and then rendered out “mid” and “far” perspectives with additional reverb, EQ and delay, and blended between the assets based on the player distance from the sound. We could have done this in our middleware, but found the quality of the assets with the effects baked in just sounded better and we were streaming all of the assets in thanks to the speed of the PS5 SSD, so soundbank memory wasn’t really a concern.

The three of us just walked around the stage, picking up, moving, dropping, and nudging objects to simulate the randomness of real life

JL: So much of what makes a believable “lived-in” ambience comes from the small, unintentional sounds that are incredibly difficult to design for. Real soundscapes are made up of countless tiny moments at different distances and perspectives — a dish sliding across a table nearby, a chair being moved a few tables away, or a neighbor closing a window a little too hard. All of these subtle details combine to create a sense of reality that feels organic and alive.

We recorded a lot of props we had on hand, but quickly realized we needed a much larger variety to truly capture that texture. We spent some time at the PlayStation Foley stage in San Diego, recording both structured and unstructured prop performances. The structured sessions were what you’d expect — performance-based movements at various intensities — but the unstructured ones were much looser. The three of us just walked around the stage, picking up, moving, dropping, and nudging objects to simulate the randomness of real life. We even used it as an excuse to clean up the stage a bit and record the sounds along the way.

The real challenge was figuring out how to play these sounds efficiently in-game without spending endless hours hand-placing or individually rigging each emitter. That’s where the new Sound Scene system we built for Ghost of Yōtei comes in. We streamlined the process of playing predefined groups of emitters, either attached to a list of characters or played at random points within a volume that can be drawn directly in our in-game editor.

These predefined groups of assets, called “scenes,” include additional controls such as time-of-day gating, minimum spawn distance from the listener, and delay time constraints. All of these can be set up ahead of time by sound designers and reused across the game. The result is a huge reduction in implementation time for ambient sounds, allowing for much faster iteration and far greater flexibility during production.

What about the weather that’s inspired by the real climate around Mount Yōtei? What was your approach to designing weather sounds — rain, wind, and snow — and building audio systems for the game’s dynamic weather?

AL: The nuts and bolts of our weather systems were mostly carried over from Ghost of Tsushima; our ‘wind rig’ is made up of four mono emitters that surround the player, independently returning what location they’re in and allowing us to continuously blend wind and environment sounds together depending on what biome(s) the player is surrounded by.

This system works really well because the player could be straddling three or more biomes at any one time, enabling them to hear the difference in environment all around them, while also reacting to wind speed and time of day. An extra thing we added for Ghost of Yōtei was to distinguish the three very distinct locations of Ezo that map roughly to the first three chapters of the game. We knew very early on that we wanted to differentiate these locations from each other in terms of weather and ambience, so we added layers to our wind rig that conveyed where in the story you were.

The area around Ishikari Plain is a windy, volatile coastal area, full of Raiders and outlaws, so we added some aggressive, turbulent sounding wind. Teshio Ridge is a mysterious mountain range where the Kitsune and the Nine Tails are hiding, which lends itself to more tonal, whispering abstract layers, and the Yōtei Grasslands and Tokachi Range is a vast plain that connects the valleys together, where you can hear distant gun shots, horse herds, and Ezo outlaws searching for Atsu. These additions, along with our Sound Scene system described above really helped separate these areas from a sonic storytelling point of view.

our rain system […] uses the same system as the wind rig, playing four mono rain surface layers around the player depending on what surface it hits

We simplified our rain system slightly from Ghost of Tsushima and now it uses the same system as the wind rig, playing four mono rain surface layers around the player depending on what surface it hits. We cast a ray down from the sky and whatever collision it hits, it gets the surface material from, and plays the proper sound of rain hitting that surface. We also have unique rain emitter sounds when you’re underneath an awning or inside a building to give a more believable quality to those very characteristic sounds.

On top of the point source sounds, rain and snow both play environment-aware 2D cubic layers (2 quads on top of one another) that help give a sense of space and height when playing in Atmos or in 3D. We decided to author these in cube to give the feeling of it surrounding you without using ambisonic assets, which, after A/Bing, we felt sounded better in all formats, and 8-channels versus 36-channels was a nice performance savings as well.

How were you able to make the most of PS5’s Tempest 3D for Ghost of Yōtei? Any particular sonic elements (environmental sounds, combat sounds, crowds, etc.) that had especially pleasing results?

BDM: We built this game natively for the PS5 and Tempest 3D, so the default output is 5OA (fifth-order ambisonics) with an additional passthrough output at 7.1 or stereo based on the listening environment. This affords us the flexibility of making most sounds point source and letting the hardware do all of the spatial calculations. It also gave us a Dolby Atmos mix ‘for free’ by downmixing the 5OA to 7.1.4.

the systems we’ve built, which are very intentional about placing sounds in 3D space […], are a key component in making the world feel alive whether you’re listening in 3D or not

I think the systems we’ve built, which are very intentional about placing sounds in 3D space (not just in a plane around the player but in full 3D around, above and below them), are a key component in making the world feel alive whether you’re listening in 3D or not. I’ll let Adam talk about the main caveats there to ensure we’re still getting good low-end and a balanced mix in both 3D and non-3D scenarios.

AL: One important thing to consider when designing for Tempest 3D audio is to decide what NOT to render in 3D. While the technology is amazing for immersion, HRTF processing can have a negative effect on the fidelity of sound, so it’s a case of weighing up what’s important to spatialize in 3D and which sounds benefit from higher fidelity.

In Ghost of Yōtei, almost all of Atsu’s foley – footsteps, clothing, weapon sheathes, etc., go through a 3D passthrough buss and are not 3D-spatialized. The same goes for the horse when the player is riding it, some weapon impacts, and combat sweeteners. Low end is an area that really suffers from HRTF processing, so where possible, we try to separate those layers and send them to a passthrough buss. It’s definitely a fine balance, but this, I think, is key to creating a good 3D audio mix.

On the creative side, how did you use sound to make exploration an enjoyable, rewarding experience for the player?

BDM: The world of Ghost of Yōtei is populated with near constant surprises for the player in their interactions, side content, and exploration. We used this game design aesthetic as an inspiration for sound design, too.

The environmental sounds constantly change and evolve based on where Atsu is and what she’s doing. We use subtle audio cues to clue the player towards some content and reward them in other instances. Our Sound Scene system allowed us to very quickly author specific audio scenes that would play at various distances to clue the player into content. So you may hear distant shouts and horse whinnys and impacts and know there’s a subjugated village over the hill. Or you hear some distant music and laughing and walla and know there must be an inn nearby.

JL: One of the core features of the Ghost franchise is the reduction of HUD elements, shifting navigation to exist naturally within the world through the Guiding Wind mechanic. The original pitch: “What if we play more wind on top of an already very windy environment to guide the player toward their objective?” is the kind of idea that gives sound designers and mixers nightmares.

We knew we wanted the guiding sounds to physically exist in the world as part of the environment itself

We knew we wanted the guiding sounds to physically exist in the world as part of the environment itself, rather than feeling like abstract design elements layered on top. Ethereal or synthetic sounds wouldn’t fit the grounded tone of the game or the story we were telling. After a lot of experimentation with effects chains and processing, and taking inspiration from Atsu’s journey, Brad created an impulse response from the shamisen we have in our Foley room. The resonance of the dō — the drum-like body of the shamisen — gave the wind a unique voice and placed it in a subtly different space, allowing it to stand out in the mix and naturally draw the player’s attention in the right direction. In Ghost of Tsushima, I used tonal flute elements, but this time around, I processed a lot of wolf vocalizations as a core element of the Guiding Wind to help tie into Atsu’s relationship with the wolf and her role as a Lone Wolf finding her Wolfpack.

Chris Walasek (CW): I’m a big fan of exploration in games and all the little surprises you can come across while running around. Like Brad had mentioned, we use subtle audio cues to guide the player towards cool content and either reward them with a new activity or some alternative paths to progression within a mission. A lot of this is accomplished with our Sound Scene system, but there’s also a handful of times where we’re hand-authoring events to help push the player along.

we use subtle audio cues to guide the player towards cool content

In more than a few spots in the game, we created triggered effects that follow the path of the quest you’d be on — you would go and interact with something, and then a bush would rustle to your right, guiding you to another interact that would then trigger a bird fly away from the forest in the direction of the next interact and so on. There was nothing so loud as a fairy screaming, “HEY LISTEN!” every few steps or so, but something that might turn the player’s attention to a certain direction where they might spot the next interact they’re looking for.

In another instance, there’s a mission where you have to navigate around this eerie area that’s supposedly being haunted by the Spider Lily General — an old war general that accidentally killed his daughter while sparring with her, and as a result has gone mad with grief. Through the mission, you need to find four keys to get into his residence and duel him.

Naturally, we wanted to accent this whole area with his wails, sobs, and screams, and the Sound Scene system was perfect for this! We could determine how far away these wails should be from the player, so as you get closer to areas where you could grab a key, we could heighten the tension by bringing those effects in closer as if this crazy, maybe-a-ghost guy is getting closer to you. Combining that with trigger events to rustle the bamboo around you, having his screams leading you to the next area, or even just smashing straight into a jump scare really made for a killer spooky feeling throughout that mission, and it ended up being one of my favorite things in the game!

What was your approach to combat sweeteners — like when Atsu sneaks up and assaults an enemy? Or when she delivers a forceful blow?

AL: On Ghost of Tsushima, each assassination attack had a baked in 5.1 sound design pass, whereas on Ghost of Yōtei we decided to utilize our variable controlled animation system that Josh outlines below to give variety, flexibility, and positional accuracy to these combat moves.

Whereas Jin was a samurai with precision and skill, Atsu is a self-taught fighter; it’s a little more improvisational and rougher around the edges, and we wanted to highlight this with the sound of her combat. Tagging each assassination with foley, weapon swings, impacts, haptics, and sweeteners allowed us to incorporate the assets we use in her in-game combat to give a continuation of this theme and tie it into the rest of gameplay. Doing it this way also gives more positional accuracy – the weapon swings and source impacts play on the weapon, the target impacts play on the enemy, and the foley plays on the characters rather than everything baked into a 5.1 asset. We generally took more of this approach for set pieces and special moves compared to the previous game, and it also allowed sound designers to polish specific sweeteners late in the project without having to redo full surround stems, as Pete Hanson did with the assassinations and others.

CW: With all of the possibilities in combat, we also wanted to add a little sweetener for using an “aligned” weapon in combat — a weapon that was effective against the enemy or weapon you could be fighting. What we did was pretty simple, but managed to work really well. Our technical sound designer, Grey Davenport, crafted a little bit of code that would set a variable we could utilize for when we were attacking an enemy with the correct “aligned” weapon type. We set this variable on the sound to branch to a different sound with a send to a reverb that Brad made, which sounds super cool, and may or may not be all over the game. And that was all it needed as a subtle tell for the player to know they were using the “correct” weapon against an enemy.

Grey Davenport crafted a little bit of code that would set a variable we could utilize for when we were attacking an enemy with the correct “aligned” weapon type

Another cool combat sweetener is the pistol parry. Based on the mechanic (and knowing the designer who came up with the idea), I knew this was pretty heavily inspired by Bloodborne. Being a lover of FromSoft titles myself, I know that when you get a parry off, it has to sound like you just did the coolest thing ever. Operating in a more grounded space than a Lovecraftian cosmic horror game, we couldn’t make it sound too crazy, but there are definitely some sweetener layers in there that pay homage to that awesome feeling from the Soulsborne titles.

What about combat reactions? How did you work these into the game so they felt real/appropriate and not overused?

JL: We knew immediately after shipping Ghost of Tsushima that we needed to rethink how we authored and implemented combat impact assets. On Tsushima, we created bespoke assets for each weapon combination that also needed special case implementation. This approach had a few drawbacks. It relied on a single shared asset between two actors, which meant the sounds weren’t positionally accurate. It was also time-consuming to create bespoke variations for every asset type, and even more time-consuming and error-prone to implement within a large monolithic playback script.

That was before Yōtei entered the picture, where the hero can equip five different weapons instead of just the katana, alongside a much greater variety of enemy weapons. The first step was to redesign the playback system to remove the special casing and move to a much simpler table lookup based on the weapon types involved in an impact event. From there, we split each impact into two sounds: the “source” (i.e., the actor initiating the attack), and the “target” (i.e., the actor receiving it).

This change not only made the impacts positionally accurate but also allowed us to create separate data sets for the source and target that complemented each other. The result was a system that naturally produced rhythmic, organic “happy accidents” where the interplay between sounds made each encounter feel alive and unscripted.

Instead of creating combinations for every possible weapon match-up, we shifted the system from ‘Weapon X versus Weapon Y’ to ‘Weapon X versus Impact Base Type’

Now, you’re probably thinking, “Wait, didn’t you just explode your asset count?” And yes, we did — but we quickly realized we could simplify. Instead of creating combinations for every possible weapon match-up, we shifted the system from “Weapon X versus Weapon Y” to “Weapon X versus Impact Base Type” (i.e., metal, chain, shield, wood, or flesh). This approach made recording, design, and implementation far simpler, while still preserving the fidelity and richness you’d expect from the expanded variety of weapons.

Did you capture custom recordings for the game’s weapons and other objects?

BDM: We love to record as much as we can in-house and Ghost of Yōtei was no exception. We recorded tons of content at our studio including various ambient and foley elements. Probably the most iconic thing we recorded was a shamisen that I found at a Japanese art market in Seattle. Josh already mentioned using it for IRs, and he’ll speak more about it later in regards to the more creative uses for it, but we did also record all of the dynamic foley for Atsu’s back with that prop, as well as the string noise heard in the shamisen minigames and cinematics.

We were also fortunate enough to record Rensei, one of the members of Tenshinryu, a 400-year-old martial arts school in Tokyo when they came to visit the studio. She performed all of Atsu’s sheath, unsheath, and chiburi (flicking blood off the blade) moves. The thing I loved about that session, beyond watching a master of her blade do these actions, was Rensei’s sword had this unique rattle to it that worked so well for Atsu. She’s not a prim and proper samurai; she’s a scrappy warrior. That detail from Rensei’s own blade carried over into the game.

But the biggest evolution for recording on this project, compared to Ghost of Tsushima, came in the form of Joanna Fang and Blake Collins — PlayStation’s internal foley team. They’re such an experienced, talented, collaborative team and they really elevated so much of the foley recording.

Using that initial spec sheet, we went down to the PlayStation Foley stage and collaborated with Joanna and Blake to expand on those ideas and capture every weapon type

JL: As mentioned earlier, we completely overhauled the combat sound system for Ghost of Yōtei, which came with a new set of asset specifications designed to achieve the rhythmic “happy accidents” we wanted to create during combat. I recorded and designed prototype assets in our Foley room to identify what worked and what did not in terms of impact timing and performance. Using that initial spec sheet, we went down to the PlayStation Foley stage and collaborated with Joanna and Blake to expand on those ideas and capture every weapon type.

We also built several custom props on the stage that were ergonomically friendly to handle during recording and designed to capture the exact sounds we needed. Joanna even commissioned a set of unique katanas from her armorer that isolated the handle from the blade, allowing the metal to resonate more freely and produce a very distinct and unique tone.

CW: Honestly, the foley room was one of my favorite places to be in the studio. I had the opportunity to record some effects for the katana, the kama (the sickle part of the kusarigama), and the odachi! Did you know you can just buy these things on eBay? It’s crazy. Thankfully, we had PLENTY of weapons around the office (haha) so eBay wasn’t needed, but getting them to sound right when hit was another process.

We found that hanging the weapon from the ceiling of our foley room and hitting it with a handful of random metal objects (e.g., a different sword, a wonky crowbar, a slab of metal, and a League of Legends-branded spatula brought the best results) really resonated the hanging weapon and gave some great results. It also led to a funny video I took for a studio show and tell in which I hit a hanging sword, which then began to spin rapidly, and I had to navigate around a flying weapon while making it not hit the Sanken CO-100K I was recording with while not ruining the recording. Fun times!

Our blood recording session was another fun, albeit messy one. We made a really thick cornstarch and water mixture (oobleck) and shook it up in containers, and flicked it with brushes against various surfaces. We also went through A LOT of grapes and cherry tomatoes, popping them in my hand and capturing that juicy, visceral explosion of gore that we then mixed subtly into the blood visual effects in-game.

Atsu can learn new songs on the shamisen, which allows guiding winds to lead her to new landmarks on the map. What did this require from the sound and music teams?

BDM: We knew very early on that Atsu would have a shamisen and that music, specifically diegetic music, would be very important to her character and her journey. We prototyped what this might look and sound like very early in the project. When we finally got to the place of being able to take this further, we looked at three different avenues to supply the music for Atsu.

We pulled some shamisen tracks directly from the score that Toma Otawa was writing — evocative melodies, beautiful passages and phrases that worked well with the minigame that we built for Atsu learning these songs.

We reached out to our soloists, specifically Yukata Oyama, and he brought some traditional folk songs from Hokkaido that we had him record.

There is a song that Atsu learns from an Ainu musician, and Oki Kano, a tremendous Ainu tonkori player, helped us out there, and then we had Oyama-san play the tonkori melodies on shamisen.

Andrew Woods […] animated most of the shamisen songs, effectively learning the tuning and fingering by listening

And lastly we actually had one of our music team members, Kelvin Yuen, record some unique pieces as well. Amongst other talents, Kelvin is a shansin (an Okinawan shamisen) player and he composed a few of the songs that Atsu plays as well.

Once we had the music, then it was just a matter of chunking up the assets into what we needed and applying the logic we built in our middleware to handle the mechanics of the game. I definitely want to call out our resident animation/music/technology wizard at Sucker Punch, Andrew Woods, who animated most of the shamisen songs, effectively learning the tuning and fingering by listening. Andrew was also responsible for playing AND animating all of the buskers in inFamous Second Son, so he’s no stranger to animating musical parts, and I feel very lucky that we’re able to have our animations match the correct fingering and rhythm of the songs Atsu (and other musicians) play in the game.

Another animator, Ju Li Kaw, took up the mantle as well and did a great job animating the tonkori and another of Atsu’s songs to match the animation to the actual playing.

How did the sound team contribute to the game’s haptic feedback?

BDM: Ghost of Tsushima Director’s Cut was our first foray into haptics. Previously, vibration had always been a systems design-led discipline, not audio, But now that the haptics WERE audio, it shifted so we owned the haptics. We do still work closely with our various systems and mission designers and get their feedback on what’s working, what isn’t, what we may want to improve, etc.

So now our process is we add haptics as we design. Rather than doing it all at the end, we try to design haptics in tandem with sounds. We did work with our systems and combat teams to do an audit of haptics across various areas of the game to get feedback from them and had one of our sound designers on the PlayStation side, Pete Reed, do a polish pass and rework tons of our haptics to make everything feel more responsive and detailed. Like much of the game, the bones were there for most of production, but it wasn’t until the last several months that things started really sounding AND feeling great.

There’s a few ways we approach haptics and each has its benefits and its uses. Mostly, we design bespoke haptic sound effects in our DAW. Sometimes this is crafting them from synths and other times it’s using elements of the original sound, EQ’d and processed. One of the more important aspects of haptics design is matching the feel and envelope of the source sound the haptic is helping convey or emphasize. We do also have a real-time haptics generation synth we can use to design haptics and play them back as a synth rather than as a waveform, though we didn’t use this quite as much on Yōtei. Lastly, we can send an existing sound to an Aux buss that we process, EQ, and route to the haptic motors. There’s instances of all of these across the game used in various places where it made the most sense to choose that specific design approach.

Pete Reed (PR): The main process of the haptics polish pass was to create bespoke authored content. This involved capturing game play and in Reaper designing haptic assets to further enhance the players game play experience. Working in tandem with the combat and systems teams, we were able to overhaul some areas where adaptive triggers and haptics were competing with each other resulting in a much cleaner and clearer experience for the player.

For game play elements like sword play, I found the use of higher frequencies was a great way to mimic holding a real swinging and ringing sword

As Brad has said, the designers had created haptic content and there were a few areas of the game where I was able to expand upon their great work.

One of the main areas I focused on was the frequency range being used. Haptics golden frequency range is roughly 40Hz to 100Hz and this is where commonly, most haptics content will fall. The coil actuators in the DualSense controller will however respond to audio content ranging from 10Hz all the way to 20kHz (it does drop a little around 1k). It’s worth noting that the higher you go the DS5 will resonate, causing it to be audible. For game play elements like sword play, I found the use of higher frequencies was a great way to mimic holding a real swinging and ringing sword.

What went into the sounds for Atsu’s companion wolf?

BDM: Our initial plan was to record at one of the wolf sanctuaries here in the Pacific Northwest. Unfortunately, around 2020, they stopped allowing visitors to protect the wolves. I reached out to them but never got a reply, so we were considering going the library route when I was reminded by someone on the PlayStation team that there were some recording sessions done for both Days Gone and 2018 God of War, so we were able to get that source and Chris [Walasek] turned it into most of the vocalizations for the wolf in-game.

I found some coyote nails on eBay, ordered them, and sewed them into some gardening gloves, which we recorded on various surfaces to get that canine walking

Chris also did the footsteps and all other wolf-related sounds. We recorded the nail layer for the footsteps in-house taking a page from Beau Jiminez when he was a Naughty Dog working on The Last of Us Part II. I found some coyote nails on eBay, ordered them, and sewed them into some gardening gloves, which we recorded on various surfaces to get that canine walking on surface nail layer.

CW: If there’s one thing you can take away from this article, it’s that eBay likely has any prop you might need. I didn’t know that Brad got the claws off of eBay; when he handed me coyote claws sewn onto gardening gloves, I figured it was better not to ask questions.

Getting those source files for the wolf was a godsend! It was a combination of those, some not-so-happy dog vocalizations, and a few bits from my own little guy at home (shoutout to my dog, Heimdall). I was able to throw something together that sounded fierce, but also curiously gentle at times.

If there’s one thing you can take away from this article, it’s that eBay likely has any prop you might need

A big thing that Brad and I talked about when designing for the wolf was that even though it is an ally to the player, it should never sound outright friendly. In the context of the story, it is a wild animal that serves as a mirror of Atsu’s own hunt for revenge. In the opening scenes of the game, you can see it is just as eager to hunt down the Snake. With this in mind, I wanted to design the wolf to reflect what Atsu could be feeling at times, whether that’s barking more the faster you go in a chase, and sounding irritated if you fall behind, or the wolf’s idle breaths becoming stifled growls as you sneak around an enemy camp looking for an assassination target.

Overall, I wanted the wolf to sound more trusting than friendly, like it could turn against you if it ever felt like it. Atsu just plays the role of a temporary ally in the wolf’s own hunt as they slowly build trust between them.

Can you talk more about the game’s foley sounds, and foley system? Did foley also help with sounds for combat? What about the galloping horses, or horse tack?

JL: Foley is one of the most important elements for grounding and immersing the player in the world. Audiences have been trained by decades of cinema to expect detailed, natural sounding foley that perfectly matches character movement. Unlike film, we don’t have the benefit of linear playback, and the situations our foley needs to support are virtually endless. To make things even more complex, the game features a wide range of costumes that can be swapped at any moment, requiring an entirely new set of foley assets to load instantly.

To make things even more complex, the game features a wide range of costumes that can be swapped at any moment, requiring an entirely new set of foley assets to load instantly

Traditionally, games rely on a shared library of foley assets such as jumps, crouches, and turns that are tagged to animations. The challenge is that these generic sounds rarely fit every situation perfectly. As a result, many teams either turn foley down in the mix to hide inconsistencies or spend enormous amounts of time creating one-off assets to preserve immersion. Because players are conditioned to expect perfect foley, anything less can immediately break the sense of realism that every team on the project works so hard to build.

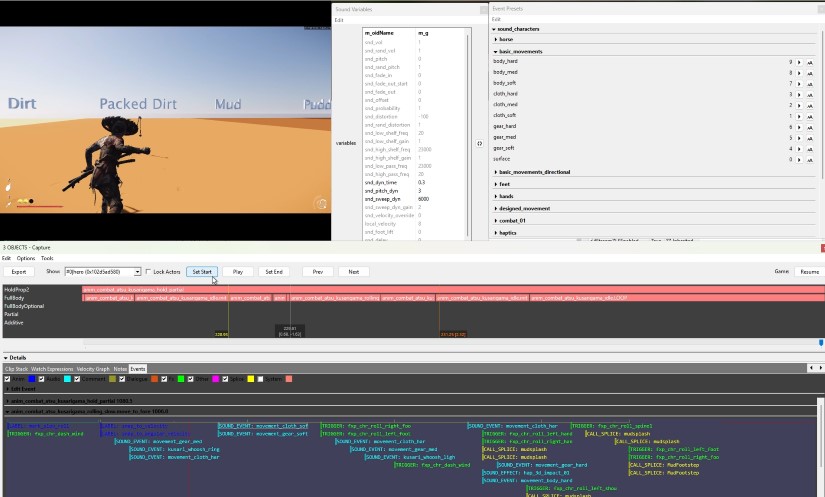

Our solution was to combine the precision of linear editing with the flexibility of a modular system. We built a highly optimized set of modular sound types that could be manipulated with the same kinds of tools you would find in a DAW. Each costume and character in the game uses a set of four core categories: gear, cloth, body, and surface, with hard, medium, and light variations for each. Sound designers then tag with these basic modular sound types to put together a custom edit for each animation to perfectly match the motion and intention.

Sound designers then tag with these basic modular sound types to put together a custom edit for each animation to perfectly match the motion and intention

We then have all of the normal DAW sound editing/processing tools available to use to manipulate each modular sound type to dial in the sound further. At runtime, designers have access to pitch, volume, high and low shelf/pass EQ, fade in/out, asset seeking, dynamic pitching, EQ sweeps, distortion, and more. The system behaves so similarly to working in a DAW that we even built Reaper scripts capable of exporting an entire session’s mix and edit data directly into our in-game format, allowing us to play it back using live game assets.

CW: Foley was actually one of the first things I touched on this project! Joining the team here, I knew that Ghost of Tsushima had EXCELLENT foley, so I was definitely eager to get into the weeds of how the systems worked. As it turned out, we actually ended up completely reworking how the footsteps functioned.

We also added an idle footstep type that was more focused on the texture of the surface rather than on the thump of the heel

Instead of using the already existing way of Tsushima’s walk/jog/run footsteps, we created a system that functioned on speed, blending the footstep types based on the velocity of the character. We also added an idle footstep type that was more focused on the texture of the surface rather than on the thump of the heel, as well as adding a sound for the lift of the toe from the surface that also had its own variations for walk/jog/run. All of these sounds were put together on a blend that added an appropriate delay for the lift. Instead of tagging animations with footstep_walk, footstep_jog, or footstep_run, we could get away with a single footstep event that handled everything by itself!

We also added onto the existing roster of footstep types from Tsushima by adding in foot scuffs, plants, turns, drags, slides, and settles. These events all gave more creative expression to work with when tagging sounds on an animation, and having a more detailed palette to choose from only makes that easier. Joanna and Blake absolutely killed it in getting those assets to sound just as we imagined ’em! (HUGE props to them for going along with my thought that a drag sounds different than a slide, haha)

Another kind of cool thing we ended up doing was adding some sweeteners onto footsteps in combat situations through the footstep event! Atsu’s fighting style is WAY more scrappy than Jin’s was, and I think the sound of the character’s footwork had a chance to help with that. Working with the music system, we were able to get an indication of when the game’s “mood” would change from exploration to combat. When this happens, we could turn on an additional layer in the footstep event that blends in a scuff or plant with a velocity-controlled distortion to feel a bit grittier. All of these things are fairly small changes, but I think the combination of them really helps in how we wanted Atsu to sound when running around.

AL: One of the coolest things about the foley in Ghost of Yōtei is our surface blending system on player and horse footsteps. Josh built this crazy complicated script in our audio middleware, SCREAM, that blends current and previous surfaces together when you traverse from one surface to another. For instance, when you transition from dirt to stone, the dirt footsteps fade out over a second or so while the stone surface is fading in. It’s a subtle detail but sounds so good!

BDM: I think the only thing I can add here is that, for the first time in my career, with Josh’s foley system, tagging foley suddenly became fun! The system is super elegant because it’s very simple (nine non-hand/foot sounds per character), but the power and flexibility we get by tweaking variables at runtime to sculpt those sounds to match every animation made tagging a joy, and we built a preset system, so it also was faster than ever to tag animations, and tweak them to get better fidelity compared to a foley system with five or 10 times as many assets.

the power and flexibility we get by tweaking variables at runtime to sculpt those sounds to match every animation made tagging a joy

Our implementers, Jessie Chang and Chris Bolte, really took to the system and the speed at which they could work through animations, and the quality they got out of it for both gameplay and cinematics is a testament to the quality of the assets and the tagging system itself.

Ghost of Yōtei can be played with English and Japanese dialogue. Can you tell me about the dialogue work for the game?

BDM: We work VERY closely with our Creative Arts partners at PlayStation throughout the project. They are as much a part of the audio team and any of us internal Sucker Punch folks. So all credit is due to the dialogue team for their excellent work on the dialogue across ALL languages and ensuring we have a consistent mix across languages.

When we were doing the final mix at PlayStation in San Mateo, we always had myself and at least one member of each audio sub-team (sound design, music, and dialogue) in the room and more folks listening in online via Evercast. We switched back and forth between languages multiple times throughout the mix process to spot check and ensure consistency and intelligibility.

In narrative-driven games, mission-critical dialogue is almost always the most important thing for players to be hearing at any given time. Similar to Ghost of Tsushima, we used a healthy amount of Dynamic EQ on our sound effects and music busses to carve out space for critical dialogue when it was playing and this has the benefit of fostering a transparent mix.

On the integration side, we treat all of our dialogue lines as external sources rather than have them living as assets in our middleware

On the integration side, we treat all of our dialogue lines as external sources rather than have them living as assets in our middleware. This makes file management a lot easier and rather than each wave needing its own sound or event to play through, we can just craft the sounds we need with the proper parameters, effects, distance modeling, etc. We break this down into mission critical lines for the hero, main characters, NPCs (effective non-main character), enemies, and peds, and do the same for non-critical lines and exerts. Each group of characters has unique parameters and grouping so we can easily mix whatever is or is not important in a given scene.

What was your approach to UI sounds for Ghost of Yōtei?

JL: UI sound design is incredibly similar to music in that it’s one of the few categories of sound that can directly communicate emotion and guide how the player feels. Great UI sounds should directly inform and strongly suggest how the player should feel about something being presented to them. Because of that, I find UI to be one of the most time-consuming and challenging aspects of sound design. It carries a huge responsibility — it has to be functional, emotional, and blend in with the surrounding soundscape all at once.

UI is also constantly evolving throughout development, since it needs to react to story changes, mission updates, and shifts in tone. Early in production, when the story leaned heavily into a revenge arc, our first pass at UI sounds reflected that focus. They were aggressive and weapon-based assets, designed to emphasize intensity and precision. As the narrative grew more nuanced and Atsu’s journey took shape, we shifted the sound palette to reflect that evolution.

You can hear this transformation in the very first menu of the game when starting a playthrough. The UI sounds in the opening settings screen are darker and more forceful, mirroring the tension of the opening scene. As the story unfolds, those sounds evolve with Atsu, reflecting her emotional growth throughout the game. That evolution is deeply tied to her connection with the shamisen, an instrument her mother teaches her to play from an early age and one that becomes a defining part of her identity. Many of the UI sounds are built from processed shamisen recordings we captured in-house, and even sounds that didn’t originate from the instrument were often processed using the same shamisen impulse response that we created for the windicator.

even sounds that didn’t originate from the instrument were often processed using the same shamisen impulse response that we created for the windicator

We were also incredibly fortunate to have access to the scoring stage during the recording sessions for the game’s score. We took the opportunity to capture samples from many of the same instruments and performers, using those recordings as additional source material for the UI sound design. That source material became a key ingredient not only for the UI, but also for many of our stingers and sweeteners. By using the same instrumentation and tonal palette as the score, the UI was able to blend more seamlessly with the music and feel like a natural extension of it.

The game’s score is a huge part of Ghost of Yōtei‘s sonic identity. Can you talk about working with composer Toma Otowa? How did his music influence the choices for sound design?

BDM: When the PlayStation team first suggested Toma as a prospective composer, I think the first thing they said about him was, “He’s really great to work with.” And they were right!

his demo delivery was three cues that all ended up in the game, almost exactly as they appeared in demo form

It’s also a testament to his skills as a composer that his demo delivery was three cues that all ended up in the game, almost exactly as they appeared in demo form. Working with Toma was exceptionally collaborative. We would give him assignments and captures from the game and he would come back with these beautiful melodies. We’d massage them collectively, and ended up with a really incredible demonstration of beauty and talent across so many amazing musicians as well as Toma and our orchestrator, Chad Cannon, who was also instrumental (pun!) on the score for Ghost of Tsushima, as well as the co-composer of Legends and the Iki Island DLC.

We made a lot of key mix decisions in the game that were tied to Toma’s music. Depending on what the player is doing, the music can be lonely, sorrowful, beautiful, tranquil, or epic. It’s such an emotional score, and we were constantly playing around with balancing all of the sounds in the game based on what the narrative and the music were making the player feel.

[SPOILER WARNING] A great example — and there are countless examples — is the cinematic where Atsu realizes the samurai she’s been riding with is her long-thought-dead twin brother, Jubei. The tension of the scene starts to build as they’re sitting by a fire and Jubei recognizes his father’s sword that Atsu is sharpening. As soon as he asks “Where did you get that sword?” a koto strums to signify something is awry and we slowly start to pull down the wind to let the player focus on this tension. Atsu makes a joke, at which point Jubei gets very defensive and says, ‘Don’t lie to me.” The music builds this tension perfectly and to keep the focus on the music and Atsu and Jubei, we bring down all of the songbirds and the fire crackling between them. You’re left with just the music and this stare down. The whole scene is very emotional and it’s not until the very end when Jubei beckons Atsu to sit next to him and catch him up on the last 16 years of her life, that we slowly bring all of the natural ambient sounds back in as the camera cranes up into the sky.

we opted to remove the sound design entirely because the music was doing all the heavy lifting in a more effective way

We were making mix decisions like that throughout production as we were getting new cues from Toma integrated into the game, and even into the final mix.

There were a few other instances where we built sound effects to hit home a big moment, like the title reveal for the game, but we opted to remove the sound design entirely because the music was doing all the heavy lifting in a more effective way.

What was your approach to mixing combat? Mixing exploration? Does the mix change when Atsu is moving stealthily/sneaking up on enemies?

AL: Combat was definitely tricky to mix! There are moments in the game where you’re fighting big groups of enemies with your allies, so there could be 20 or 30 people all in combat at the same time, combined with bo-hiya explosions going off, and buildings on fire in the background. It’s impossible (and undesirable) to hear all that stuff at the same time, so we did a lot of subtraction in those moments through dynamic EQ, listener cone scaling, and instance optimization to allow players to focus on what’s most important.

For example, NPC weapon swings and impacts get attenuated and filtered when they’re outside of the listener cone, meaning action that is happening off-camera will be quieter in favor of the things you can see. We were able to alter the angles and attenuation values of our listener cone as well via our Sound Mix Mod system. So, when in combat, we brought the angles in and increased the attenuation, which helped focus the mix to what you are seeing.

We also significantly reduced the maximum number of sounds that can simultaneously play while in combat. For instance, there’s no need for the quietest foley sounds, or subtle tree creaks to play when there are explosions going off right next to you. We were able to switch these settings seamlessly during runtime, and that helped massively in these big combat moments.

We also made good use of dynamic sidechain EQ to sidechain weapon swings to weapon impacts

We also made good use of dynamic sidechain EQ to sidechain weapon swings to weapon impacts. So when Atsu swings at an enemy, as soon as her weapon makes contact, the swing gets attenuated by a few dB on various bands where we want the impact to really push through. This helped give weapon impacts more space in the mix, and contributed to that satisfying crunch you get when killing an enemy.

BDM: We also have a multi-state mix system tied to enemy awareness when Atsu is sneaking around stealthily, engaging in combat or when enemies are alerted to Atsu’s presence but not actively engaged with her. Depending on which state you’re in, we affect different parts of the mix, so we actually turn down most of our ambience and various other categories of sounds when you’re in combat so the player can focus more on the combat sounds.

As far as sneaking around, we turn up enemy footsteps slightly to give them more presence and give Atsu a bit of an advantage to locate and assassinate them if that’s how the player wants to approach the encounter.

What were some of your biggest mix challenges on this game?

BDM: One of the bigger challenges on most games that I’ve worked on is ensuring that critical dialogue is always audible. At Sucker Punch, we always want to ensure our mix changes are transparent (unless we’re making a creative decision otherwise). As mentioned elsewhere, we rely heavily on dynamic EQ as this is the most transparent way to affect a mix and were EQing both sound effects and music based on mission critical dialogue.

But we also used plenty of other common technologies, like sidechaining and mix snapshots, in the service of keeping the VO intelligible. One simple yet effective thing we built was a mix snapshot that turned various ambient and character sounds down when in a walk-and-talk conversation with an NPC. I then wrote a very simple script that scaled the mix amount based on the player speed, so if you were standing still there was no change to the mix, but if you were, say, galloping on a horse, we would turn down the horse and wind slightly so it wasn’t competing as much with the dialogue.

When we started the final mix for Ghost of Yōtei, we also noticed the game was exceptionally loud (we were clocking around -18LKFS after 6-8 hours of gameplay). Most of the loudness was in combat and UI. We needed to tame the overall loudness without affecting the balance of the game. Fortunately, Josh and Grey built our Sound Sensei tool (which we’ll talk about more below) that allowed us to change the rules of loudness on various categories of sounds, hit a button and those sounds would be re-processed, reintegrated into the middleware with banks built and we were good to go. This was another example where taking some time early to build tools focused on both short-term and long-term needs really paid off.

I think the biggest mix challenge was smoothing out transitions, since it’s such a major point of polish and often requires the most manual work. Whether going from gameplay to cinematics and vice versa, or warping across the map, we want to ensure that the sound transitions are always smooth and never harsh. The other challenge was more specific to hands-off scenes, either in cinematics or dialogue where we had a point source emitter somewhere and quick camera cuts. Static sounds like fires and waterfalls were the worst culprits. We didn’t do anything super elegant, but our solution was effective: in these scenes, we would fade out the positional sound and fade in a 2D version. We also extended the variable controlled system from our animation to allow us to control these 2D sounds throughout a scene over time so we could cheat perspective and the like. We spent a lot of time both in production and in the final mix doing our best to ensure that the mix was smooth and consistent through the entire gameplay experience.

Static sounds like fires and waterfalls were the worst culprits […] in these scenes, we would fade out the positional sound and fade in a 2D version

But all in all, the mix was actually quite painless. We gave ourselves ample time; Sound Sensei effectively pre-mixed the game for us. We pre-emptively built mix frameworks for most of our mission before going into the mix, so it was largely just a matter of playing the game and making subtle adjustments and really tuning transitions.

AL: As Brad mentioned, the mix went remarkably smoothly on this game.

We did have those couple of big challenges to address when we first started, but having a tool like Sound Sensei massively increased our productivity and made big global changes more predictable and easier to manage. We knew going into the mix exactly what loudness each asset was sitting at, and by changing just one line of a script, we were able to re-render thousands of assets in one go, which we did a couple of times in the first week or two of mixing. Having strict loudness rules on assets going into the game also meant we could tune our dynamics processing easily and really dial it in in a predictable way.

Can you talk about ‘Kurosawa Mode’ for Ghost of Yōtei? What went into the ‘old film’ filter?

BDM: We did a complete overhaul on the Kurosawa mode for Ghost of Yōtei.

Previously we used what was effectively a FutzBox clone developed by Nick Ward-Foxton, one of the amazing audio programmers on the Tools and Technology team at PlayStation. This time we did a much simpler effect that is effectively just some EQ and compression, using another internal PlayStation tool called Seismix, which is effectively a modular effect processor useful for building haptics patches or complex effects.

The thing I love about the effect this time is that we actually crafted the mix of the effect much more intentionally. Since we’re trying to emulate that old, tinny 1950s feel without sounding terrible, I opted to fold down the entire mix to mono, and remove the LFE channel entirely. It’s real subtle and I don’t know that anyone has noticed it yet, but I do love how switching over does make the whole thing gel with the visuals in a very subtle, but effective way.

What were your biggest creative challenges on Ghost of Yōtei?

BDM: I think we’ve mentioned a lot of the creative challenges above, but when you’re working on a sequel to a well-received game you want to not screw it up, but also make it sound better.

This game was in every way a sequel, but it was also very different — different time, different place, different hero; so, beyond understanding what a Ghost game sonically is, the team also needed to figure out how to maintain that feel while evolving many of our systems.

a pragmatic approach to understanding scope and assessing features and content to do more with less, enabled us to pull off what we did with the game

Once we figured out things like our foley system and what the framework for those sounds were, or what our metrics and effects chains looked like for our Sound Scene elements, everything clicked in place for each of those systems, and in many ways it made the journey of designing and implementing easier.

We also talked a lot about the combat changes and how going from one weapon to five for the hero had the potential to blow up our asset count and how we avoided that by rethinking our approach to focus on the source impacts against more basic target materials. This kind of thinking, a pragmatic approach to understanding scope and assessing features and content to do more with less, enabled us to pull off what we did with the game. You see it in nearly every system and every facet of the game’s soundscape: making smart decisions to enable the team to do more with less. This allowed us to take the time and really craft those individual sounds with care.

What were your biggest technical challenges? And how did you handle them?

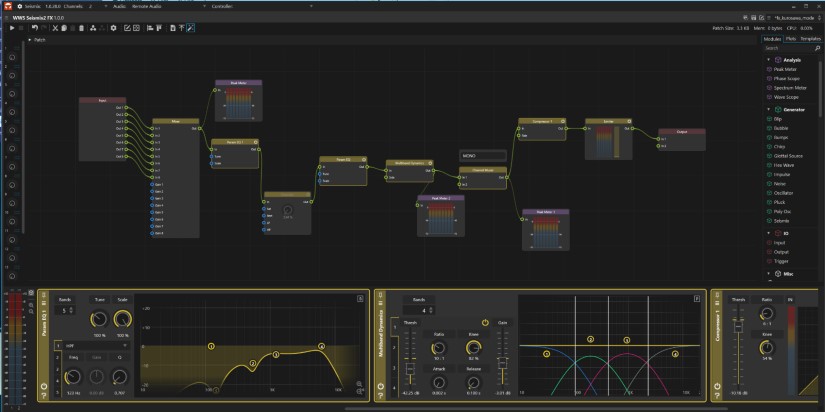

BDM: Our biggest technical challenge was that need to do more (i.e., more content, more biomes, more space to traverse, more weapons, more outfits, more missions, etc.) with less time and a similar-sized team compared to Ghost of Tsushima. We spent a lot of time focusing on and refining our systems to make them do more of the work so we could focus more on creating great content and speeding up the implementation process. Josh built a tool called Sound Sensei (that he can speak about) that effectively pre-mixed the game for us, handled a lot of implementation into our middleware, and kept us diligent on file naming.

Sound Sensei […] effectively pre-mixed the game for us, handled a lot of implementation into our middleware, and kept us diligent on file naming

JL: The challenge with a large open world is learning how to properly scope and control assets so they can be processed, maintained, and iterated on efficiently. We needed a rock-solid mix throughout development so sound designers could confidently create new sounds that already sat naturally within a near-final mix. A common issue on large projects is creeping asset loudness wars where content creators unintentionally compete for space in an unmixed soundscape. It’s not anyone’s fault — it’s just a natural reaction to working without clear mix reference. But, it often leads to over-compressed or overly EQ’d assets that lose their natural dynamics. Once you reach the final mix stage, those sounds are already pushed too far, making it difficult to rebalance them within a more refined mix.

Mixing your own content is also challenging because it’s hard to stay objective when you’re so close to the material. You need an unbiased system to help keep levels consistent across the board. For us, Sound Sensei became that objective mixer. It sits between our DAW and our audio engine, automatically detecting changes in our sound directory and processing those files before implementation or refresh.

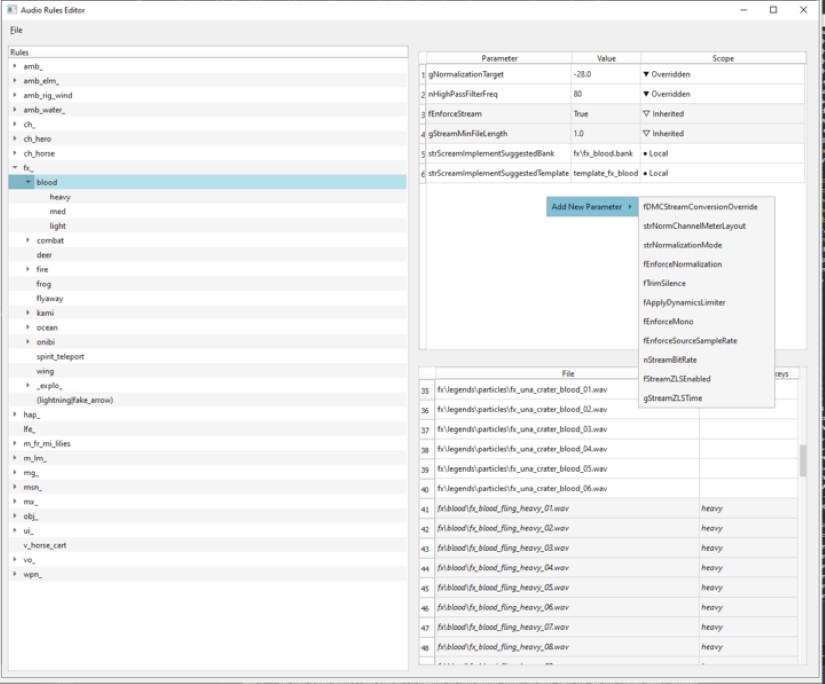

The most important processing Sound Sensei handles is LKFS volume normalization, but it also performs tail-silence removal, dynamic limiting, high-pass filtering, format conversion, channel management, and a range of processes specific to SCREAM. It uses a nested tree of rules that determine how each asset should be processed and implemented based on file naming. By enforcing consistent loudness and processing standards through this system, every asset enters the game correctly mixed, and any revisions maintain the exact same loudness as before.

On a project of this scale, it’s simply not possible to hand-process and mix every file. With Sound Sensei, we can make large-scale mix adjustments to entire categories of sounds just by updating a rule, which keeps the mix stable while allowing rapid iteration. Making a large-scale game’s data feel small and manipulable allows for more iteration and mix control. There’s a lot more happening under the hood, but in short, Sound Sensei dramatically sped up our workflows and helped maintain a consistent, reliable mix across the entire production. For a deeper dive into the technical details, check out Grey Davenport’s upcoming GDC talk this year!

What have you learned while working on the sound of Ghost of Yōtei? How did this game help you to improve your craft?

BDM: Every project is such a great learning experience and Ghost of Yōtei was no different there. The team was operating at a higher level than ever before through a combination of cooperation, teamwork, brainstorming, and some really nice tools. Much in the same way we leveled up our skills in making Ghost of Tsushima, I feel we replicated that even more successfully on Ghost of Yōtei and I look forward to using this as a springboard to whatever we end up working on next.

much of the success we had with the sound in ‘Ghost of Yōtei’ was established early in development

JL: Embrace pre-production. It’s easy for audio teams to fall into a post-production mindset, but much of the success we had with the sound in Ghost of Yōtei was established early in development. Taking the time to simplify systems, reduce asset complexity, and plan intentionally at the start made the final months of production far smoother. I’ve learned that doing less, but doing it smarter, often leads to better decisions that scale well and ultimately sound better than brute force.

AL: The thing that really stood out to me was the amount of collaboration and trust that was evident all the way through development. To make a game of this size, you need to have complete synergy all the way through the team. The team at Sucker Punch are incredible at what they do, and even though I am not technically part of Sucker Punch, I felt fully integrated into their team and felt the trust of Brad, the audio team, and everyone else at the studio. Making games is hard, and the studio has a fantastic process, with clear goals and a strong creative vision that everyone buys into.

CW: Honestly, way too much to answer here!

I think something super interesting for me that was different from other projects I’ve worked on was practicing historical accuracy when it comes to designing sounds, rather than trying to make everything sound cool. Having restraint in that led to making some of my favorite sounds I’ve made for a game. I’ve learned more about dogs in 1600s Japan and the inner workings of a tanegashima rifle than I ever thought I would. I even learned some Wabun code (Japanese Morse code) for a cool easter egg I added to the Undying Shogun mythic mission. This game was so fun to work on and I’m so stoked I got to do it with all the super cool people on this team!

A big thanks to Rev. Dr. Bradley D. Meyer, Josh Lord, Chris Walasek, Adam Lidbetter, and Pete Reed for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at the sound of Ghost of Yōtei and to Jennifer Walden for the interview!