DS = Doug Siebum

DB = David Barber

DS: Can you tell me about how you got your start in film sound and how you found your way into dialogue editing?

DB: My love of cinema goes all the way back to that first Star Destroyer flying over my head in 1977. I was blown away! That started a love of going to the movies. And it wasn’t necessarily the sound at that point, but the whole movie-going experience – even though we all did make the lightsaber and “pew pew” sounds when playing. Everything from Raiders of the Lost Ark, to Amadeus, to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, to The Untouchables, the idea of cinema was magical.

As a kid, teen, and on into college, my focus was more on playing music. At UCSB, I met and played in bands with a great singer/songwriter named Jeremy Kay and a few years after we graduated, he got signed to Surfdog Records (Brian Setzer Orchestra, Pato Banton, Butthole Surfers.) We released a few records, had some songs in movies and on TV shows, and toured the country a couple times into the early 2000’s. We’re still good friends and do projects together from time to time. During the whole experience of pursuing music in L.A., I worked in the mail room and operations department at Saban Entertainment. I made a lot of good friends there and when music came to a close, one of those friends suggested that sound for film or television might be a good fit for me. I started to talk with people in the business and tried to get on to any stages I could, to see what people were doing. I thought it was fascinating!

The best advice someone gave me early on was, “Read David Yewdall’s book “Practical Art of Motion Picture Sound.” I read it cover to cover several times. I took out a big loan against a credit card to buy some equipment, pay off my car, and keep a little in the bank to live off for at least a year. Someone steered me toward the website mandy.com where there were a lot of ads that said “do sound for our film for $500.” I was answering anybody and everybody that would let me work on their film. One of those random calls connected me with a guy who wanted me to do the sound, but he wanted to mix up at a place called Juniper Post in Burbank. Early in the post process, he literally walked me in their door. I took the opportunity to ask someone there on the side, “Hey, are you guys hiring?” They said no and I said thank you, and that was that. About a week later I got a call from them and they had an influx of M&E’s (music and effects mixes) that they needed to create. They asked if I had been hired yet and I said “no” so they said “come work for us!” That’s were I’ve been for the past 18 years.

DS: How did you get into the dialogue side of things or were you just doing everything?

DB: At that time it was everything. Very early on I was doing a lot of AFI shorts. We’d be overseen by an experienced designer/mixer but it was a great training tool for me. I got to do everything. I’d get a film and cut the dialogue, shoot the ADR, cut the ADR, step the foley, cut the foley, cut design and backgrounds, then mix. Everything. Soup to nuts, you were in charge of these projects. In the music world, I really loved being in the studio. I loved tracking and mixing. And that’s what I wanted to do at Juniper, get into the mix chair somehow. It was really a “put me in coach!” kind of mentality, whether I was ready for it or not.

Every single project to date, 17 or 18 years later, is a brand new puzzle.

It became clear very quickly, especially after reading all those books and talking to people, that dialogue is king, and that it was something I really needed to get a handle on. I would cut dialogue as often as I could. I love it. I love puzzles and challenges. Every single project to date, 17 or 18 years later, is a brand new puzzle. You definitely develop some shortcuts and tricks based on previous experiences, but with each project, the material is new and different every time. There are different actors, different performances, different locations, different mic setups, etc. etc. I find it to be a very fun and challenging aspect of sound.

DS: How do you lay out your session for editing dialogue?

Very, very recently, like over the past 18 months, I’ve expanded that due to Auto Align Post (now Auto Align Post 2) by Sound Radix, which gives you the ability to phase match the lavs to the booms, really helping to sweeten the dialogue sound itself.

DB: That’s kind of evolved for me over time. My basic layout is: Dialogue tracks 1 through 8, a couple of Futz tracks, a couple of PFX (production effects) tracks, and then your X tracks. Very, very recently, like over the past 18 months, I’ve expanded that due to Auto Align Post (now Auto Align Post 2) by Sound Radix, which gives you the ability to phase match the lavs to the booms, really helping to sweeten the dialogue sound itself. Now I find myself cutting both quite a bit. I cut the boom track, cut the lavs in support, and then pick and choose one, the other, or both as I go through the show. A lot of times, with the production sound, one mic or the other isn’t 100% of what I want. Auto Align Post giving us the ability to use both of them together has really been a blessing. It’s really cool. It does double up your work though!

DS: Right, so you’re double cutting everything?

DB: Pretty much and double filling too. You can’t exactly fill the lav the same as you fill the boom, because there might be scratches or movement in the fill. So you have to find different fill for each element. Going back to track layout, I now find myself splitting the dialogue by source – Dialogue Boom 1-6 and Dialogue Lav 1-8.

DS: What software and plugins do you use?

DB: I’m working in Pro Tools. As far as plugins, Izotope RX is my go to, because you can do so much in one tool and it’s very effective on just about everything. They do set up the defaults to be impressive, but for general dialogue cleanup, they’re too much for what you need. You need to explore what the tools can do and then back it off to your specific needs. Absentia DX is a very handy tool and I use it quite often. Another one that I’ve really become a fan of, is Acon Digital Extract: Dialogue. Thomas Boykin did an Izotope RX, Acon Digital Extract: Dialogue, and Cedar comparison that I thought was very interesting. The price point on the Acon Extract: Dialogue was so reasonable, I couldn’t not add it to the toolkit! I’ve found a setting I really like on it for de-hissing or getting out RF noise. That’s one thing that you learn about all of the tools is that each one handles a certain something really well. For example, I still use Waves X-Crackle to get the “dust” off the top of some dialogue. It’s not necessarily De-Clicking, but it does a nice job just getting the very top little spittle or top little hiss issue out on the very high end transparently. I also have the Waves W-43 inline on my tracks to handle any final noise suppression as I’m playing through a mix.

DS: And of course, you use Auto Align Post.

DB: Yes.

David Barber’s masterclass on using Izotope RX

DS: When it comes to mixing, do you have any favorites for dealing with dialogue? Like compressors, EQs, etc, that work well for dialogue?

DB: I’m a big fan of the Fab Filter stuff. I use the Fab Filter Pro-C 2, Pro-Q 3, and just on my master bus I have the Pro-MB that does a nice little touch at the end. Those are all great. I mentioned the W-43 just to catch a little noise here and there. Also, the McDSP SA-2 is wonderful.

DS: Can you tell me about your process for editing dialogue from start to finish?

DB: Sure. I’ll put a little asterisk by this one and say that it’s always budget and time dependent. We know as dialogue editors, we’re often asked to do the unreal. If that means batch crossfading the entire AAF, hitting play, seeing where it bumps you and fixing it, then so be it. That sounds ridiculous, but sometimes that is the process due to their budget and time constraints. Of course this is undesirable and hopefully producers and directors understand the importance of sound and budget adequately.

I’ll go through and smooth and fill the entire film, but I do it without processing. I’ll edit out the bumps, ticks, and clicks but won’t do so by processing just yet, and just fill and smooth the entire show. Once I have the entire show filled and smoothed, I duplicate and hide all of those tracks before I start any processing.

If time and budget are substantial (or even modest), my first step is to rebuild the dialogue track using the polywavs from production. I use the EdiLoad software from Sound In Sync for rebuilding. Then I’ll go through and make mic choices. After I’ve made mic choices on the entire show, I pull up the mic choices to my dialogue tracks and organize each scene, depending on what the scene requires or presents to you. That could be separating the tracks by ambient noise (same noise on same track), or by camera angle, or by character, based on the material. Usually, organizing by ambient noise mirrors the camera angles – master, single, single, etc, and this allows the mixer to more easily work their de-noising or noise suppression by track. Next I’ll go through and smooth and fill the entire film, but I do it without processing. I’ll edit out the bumps, ticks, and clicks but won’t do so by processing just yet, and just fill and smooth the entire show. Once I have the entire show filled and smoothed, I duplicate and hide all of those tracks before I start any processing. Now there’s a raw but edited version that exists to go back to when needed. Then I go back and start my processing cleanup of the dialogue – bumps and ticks and so on. The final thing that I do is go back and check my edit against the scratch track that came from editorial. Every once in a while you catch an alternate take or a wild line that you missed. It’s very important to go back and check it. It’s really bad to get into the mix and the client says “what happened to that line?” and you not knowing about it.

DS: Do you have any tips or tricks that you can share?

DB: I don’t know how much of a tip or a trick it is, but I use Izotope RX extensively in creating fill. You have pieces that used to be unusable, because you had to chop them up so much to get the little anomalies out, but now you can just process them out and end up with a larger piece of audio. Then I like the rule of 3. I take that new piece of fill that I’ve cleaned up and duplicate it twice so there’s 3 of them. Take the middle one and reverse it and consolidate the 3 clips. Then I throw that into Izotope to see where the edges are, or if it bumps at all. Generally, using that rule of 3, taking one piece of fill, duplicating it twice, and reversing the middle one, gives me everything I need to get in and out of a line of dialogue or to cross noise floors smoothly between lines of dialogue. You can even double or triple that new piece of fill to extend it.

The other tip I would say is just listen a lot. If you can listen in a theatrical environment, great. If you can listen in a studio, great. Take your favorite soundtracks over the last however many years and listen. Sometimes I’ll sit in my room and I’ll solo the center channel and listen to entire scenes or even an entire movie. Just monitoring the center channel to see what they put in there, how the dialogue is, and how much noise is left in or taken out, what foley or ambiences are there, is any music leaking in to the center channel, etc. Flip flop that and mute the center channel to hear how verbs and delays are used on the dialogue around the room.

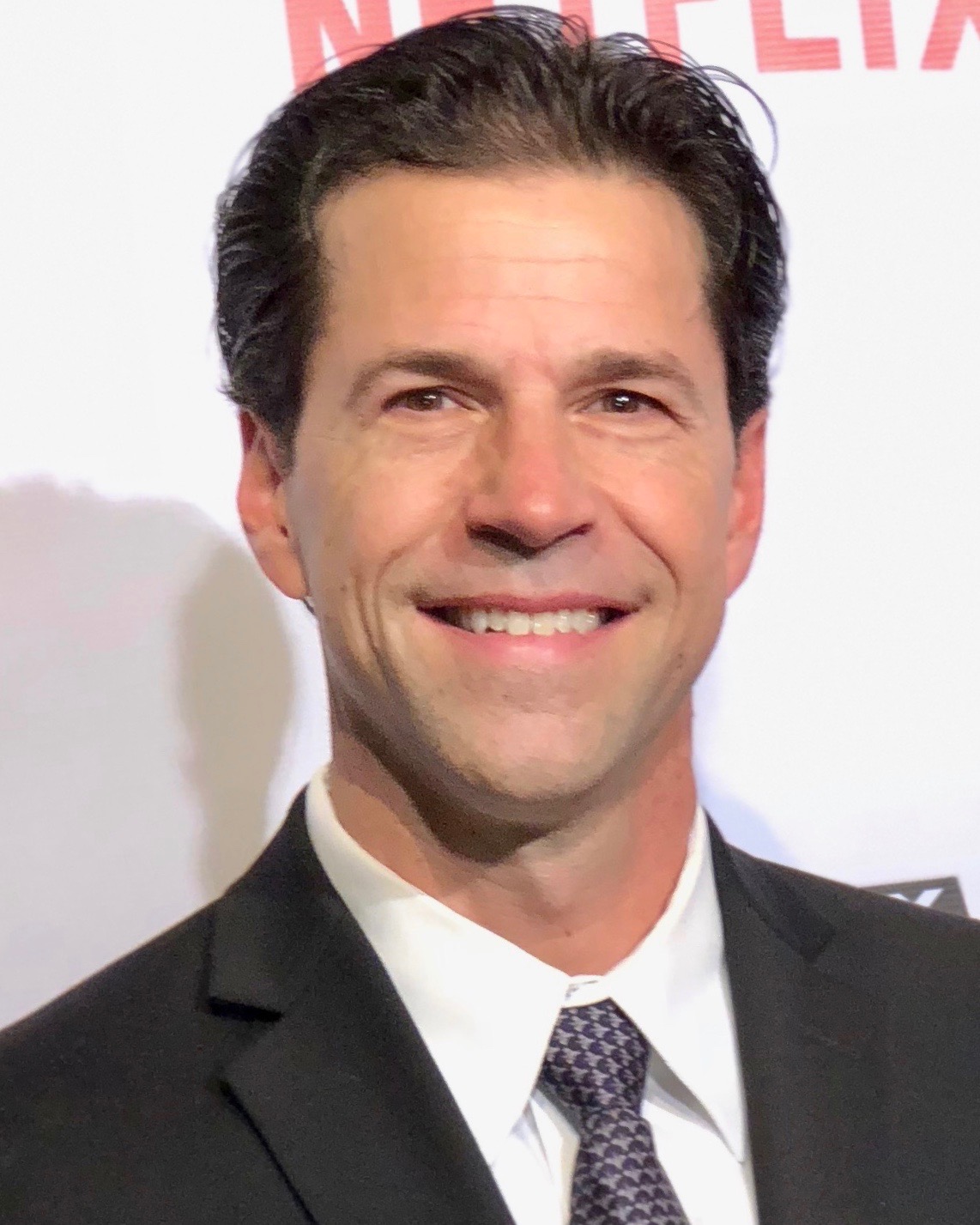

Peter Albrechtsen and David Barber in Copenhagen, photo by Robert Machoian.

DS: What’s your favorite software for generating room tone?

DB: I like to get room tone from the tracks themselves. With the rule of three, I can usually get the fill I need out of that or even create a nice room tone to lay as a bed if I need to. The newest version of RX 9 Advanced has a much improved Ambience Match. You need to have a pretty good size sample. Recently I was able to generate the feel of a church using the RX Ambience Match, which was great. I was able to grab a good chunk of production room tone with pew and people movement, pop it into Ambience Match and the algorithm randomly varied where the noises ended up so it didn’t sound “looped” while keeping the room tone constant. It ended up being a very nice bed for a church scene. I haven’t explored too many other software options to generate room tone from scratch. I still like to find it in the dialogue itself.

DS: Is there ever a time when you say “I can’t fix this”?

DB: Yes. That has become less and less and less over the past decade because of technology. There are still things that just can’t be fixed. Proximity is one of them. If the actors are too far from the mic or the noise floor is too high or there’s a really bad signal to noise ratio, those challenges continue to be difficult to overcome. Extensive dialogue overlap is also something that you can’t really get rid of yet. Even though you can do a lot with Izotope RX, digging in between the frequencies and pulling out parts of another person’s voice, at a certain point it’s too much surgery and you’re just ruining things. You just have to find an alternate take or loop it.

DS: Do you coordinate to get lines covered by ADR?

DB: Yes. I cue a lot of the ADR myself. I try to keep the ADR line counts to a minimum. There are times when ADR can really elevate the sound – creative adds, adding breaths and efforts, and sometimes a really, really good actor can change or elevate their performance, while maintaining sync. For the most part, the directors, and editors, and producers, are very tied to the performances that they chose in the edit. They chose those takes not only for visual reasons, but also for performance reasons. With all the tools available now, I try to respect those decisions as much as humanly possible, and cue only what is needed. And usually even that just ends up being a safety net.

[tweet_box]David Barber shares tips and tricks on dialogue editing and mixing[/tweet_box]

DS: What do you do to help ADR fit into a scene or match the other location sound? That can be a little tricky sometimes.

DB: It can be. I think the rule on that is – do what you have to do to get it to match. For example, to mimic noise tied to dialogue in production, I’ve used the stock LoFi plugin, adding like, .1 distortion or .1 or .2 percent of noise. Sometimes you have to dirty up your ADR to make it fit in. Otherwise you have this clean piece of audio that just sticks out. The main barometer I use when choosing between ADR or production is, which one doesn’t take me out of the experience the most. 80-90% of the time we end up living with a little noise in the production sound.

When blending in ADR, my go-to first step is to use EQ Match in RX. I set it at about 95%, and that usually gets me most of the way home. It’s really nice tool. It’s not just a straight EQ of the frequencies, it actually brings over timbre a little bit. It affects not just the voices, but the background of the ADR recording as well, and that seems to make it sit a little bit better.

DS: Since you’re a mixer as well, do you have any tips on mixing dialogue?

DB: Don’t over process during the predub. During the final mix, it’s really hard to unravel and go backwards, but it’s really easy to take it a step or two further if you need to.

Listen to great mixers. Listen to Tom Fleischman, Onnalee Blank, Gary Rizzo, Ron Bochar and so many others! Listen to what they do and listen to what they didn’t do!

I would also say, listen to great mixers. Listen to Tom Fleischman, Onnalee Blank, Gary Rizzo, Ron Bochar and so many others! Listen to what they do and listen to what they didn’t do! If picture goes to a wide shot, did they play the perspective on the dialogue or did they not? If they did one time and not another, why? How does it serve the film and the story?

When mixing a scene, a reel, a film, I sit back and try to be a viewer. That’s really hard because when you’re mixing, you’ve made a bunch of decisions (levels, EQs, Verbs, Delays, etc.) and you’re conscious of those decisions. So it’s hard to sit back and watch a scene as a member of the audience, but it’s important to do. If you get sucked into the scene, then you did your job. If you’re not sucked in, you might have a little more work to do.

The Killing of Two Lovers

DS: Continuing with mixing, do you have any tips for pushing dialogue further back in a scene like it’s across the street for example? And then conversely, how do you bring dialogue forward?

DB: In terms of pushing it farther back, your first line of defense on that would be volume. Reducing volume can make things sound like they’re a little farther away by just being a little softer. Beyond that, attend to the quality of the voice. Think in terms of frequencies and resonances from that perspective. If you were standing across the street from someone, would they have a lot of low end in their voice? Would it be resonating like they were in close quarters? How loud are they speaking? If they’re yelling, do you need to put a little slap back delay on it to give it some of that distance and put it in that environment? If they’re just talking normal level, would their voice be reverberating much or at all? To bring dialogue forward, again, volume would be your first step, then working with the environment and frequencies. It’s tough to bring off-mic dialogue forward or more present because it is, by it’s very nature, distant.

DS: Yeah, that’s one of those things where you go looking for the frequencies like “can I put more bass in there,” but there’s not bass there because it’s off mic.

DB: Correct. Or if you do that, you might be bringing up the boominess of the room or the low end of the ambiences but not necessarily in the quality of the voice.

DS: With technology being what it is and so many software options, how do you preserve some of the natural sound of the dialogue?

DB: That is very important. I like the dialogue to remain as natural as possible by peeling off the smallest of layers at a time. Also, I don’t like to ask any one tool to do too much. After each step, you A/B it. Ask yourself “Have I gone too far?” As far as knowing what the natural sound of the dialogue is, keep referencing back to the audio at its initial state. It should become pretty clear when you’ve taken it too far. I try to stop two steps short of that during the predub. If I do need to do a little more de-noising in the mix, I can do a little bit more at that time.

DS: Right. To me it’s one of those things where I’d rather have a tiny bit of noise in it than have it be over processed. You can live with a little noise and you can’t live with over processing, right?

DB: Absolutely. And we’ve all over processed. We thought we did a good job, and then you listen to it a week later, and you think “oh my goodness, what was I thinking?!”

DS: You were working too long that day, right?

DB: Ha! Yes, or you obsessed over one small thing for too long a time. It’s definitely a trap you can fall into. Knowing when to stop is very important.

Pen15 Season 2, Part 2

DS: How do you deal with internal dialogue, like it’s supposed to be in the character’s head?

DB: That’s going to be situational. If it’s dreamy, I like to add a nice designy reverb to it or some delays. I really like using Slapper. That’s a fun tool. Sometimes if it’s comedy and they’re having a conversation with themselves, going drier can be equally as effective. So it really is situational depending on what the story’s calling for.

DS: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

DB: Yes. Thanks for doing an article on dialogue editing itself! I think it’s an under-appreciated aspect of audio post. A friend of mine, dialogue editor Ryan Cota, recently said “there’s more magic that goes on in dialogue editing than in Fantasia!”

DS: I love that quote.

DB: It’s a fun quote because it is true. There’s a lot of work, a lot of skill and artistry, and a lot of magic, that goes into making a production dialogue track sound “normal”. So I think it’s great that you’re highlighting dialogue editing.

DS: Thank you. I’ve wanted to do this topic for a long time. I get a lot of indie films. For low budget indie films, I feel like the dialogue editing is the most important part, because if the dialogue is off, the whole thing is going to feel off. I could mix the film as is, and the levels are right and everything, but if the dialogue is off, it’s not going to be good.

DB: You’re absolutely correct. The easiest way to make a low budget film sound of a higher quality than its budget, is getting the dialogue right.

One other thing I’d like to mention to dialogue editors that are coming up is to not get caught up too much in the de-noising world, especially in terms of ambient or broadband noise. It’s about making a smooth dialogue track where noise floors hand off to each other so smoothly that the listener doesn’t perceive the change. It can be a noisy dialogue track, a moderately noisy track, or a quiet track, as long as it’s smooth and level and free of defects (ticks, pops, bumps.) When you give it to the mixer, they can now de-noise the smooth track. All of the noise should come down relative to the neighboring noise. Conversely, if you have a quiet lav, then a noisy boom, then a quiet lav, you’re going to have your sound jumping all over the place. It really, really is about creating a smooth track.

A great big thank you to David Barber. You can find David Barber on IMDb here.