The Midnight Walk — available on PS5 and Steam (fully playable in both standard and VR modes) — is a first-person dark fantasy adventure game developed by MoonHood and published by Fast Travel Games. Over 700 clay models, 3D-scanned into the game, were used for creating the characters’ stop-motion animation. The style is reminiscent of The Nightmare Before Christmas — dark yet endearing. The player takes on the role of “The Burnt One,” whose mission is to help a creature called “Potboy” safely reach the summit of Moon Mountain.

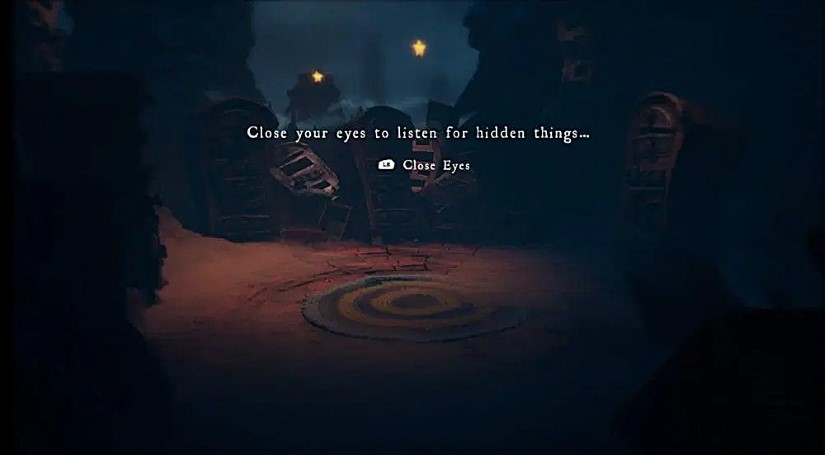

One key mechanic to solving the game’s puzzles requires the player character to close their eyes and listen for audio cues that will direct the player to their objectives. This mechanic can also reveal secrets of the game’s world, remove obstacles, and even stop hostile attacks.

Here, Lead Audio Designer/Lead Programmer Ola Sivefäldt and Senior Sound Designer Christian Björklund talk about matching the organic sonic aesthetic to the visuals, creating sounds for the VR and flatscreen game simultaneously (it’s the same audio for both game experiences!), the challenges of working within Unreal Engine 5’s audio pipeline, designing sounds for specific characters like Potboy and the Molgrim, building spooky ambiences, working with composer Joel Bille, making the most of the Heightened Sense mechanic, crafting a coherent final mix without actually final mixing, and so much more!

The Midnight Walk – Official Launch Trailer

What were some of your goals/ideas for sound when you first started working on The Midnight Walk? How did that list of ideas/goals evolve as your work on the game progressed?

Ola Sivefäldt (OS): When I first saw the mockups and concept sketches for The Midnight Walk, my immediate thought was to keep the sound design as organic as possible — nothing should feel synthetic.

Also, working with samples and recordings as a baselayer is what I feel most comfortable with. The aesthetic — clay models, cardboard houses, a stop-motion feel, and entirely handmade assets — gave the world a very tactile, physical quality. I felt the audio needed to reflect that somehow.

Early on, we even considered designing all the sounds to stay within the world of clay — using only clay, stone, and similar materials as source elements. But we quickly realized that approach was too limiting. There’s only so much variation you can get from those textures. After a while, everything started to sound too similar, and we had to expand our palette to introduce new sonic elements and keep things interesting.

Another core goal was immersion. I didn’t want the sound to just follow the visuals — to simply tell the player what’s happening on screen. I wanted it to root the player in the world. The sound had to be an active part of the experience, reinforcing the mood and making the environment feel alive.

Christian Björklund (CB): Yeah, I visited the studio to see an early version of the world in VR. It was all sort of still, almost rigid, and totally quiet. In my mind, I could imagine something very suggestive, like an abstract walking simulator with some sort of dark ambience soundtrack where you couldn’t separate what’s sound design and what’s music, like some sort of weird ASMR vibe to match the highly detailed textures, but more eerie than comforting.

Well, that didn’t happen. The next time I saw the game to work with it, it was already quite full of life and roaring monsters. Music and dialogue were present everywhere, and with time, the environment also got more and more animated. As I came in for the last six months or so, all I had to do was follow Ola’s lead and adapt to what I heard. As a freelancer, I’ve gotten pretty used to jumping on a project towards the end phase, as this is usually when the panic sets in. In a way, I enjoy that — even though it’s a bit much, there often isn’t time to overthink anything. You just go in head-on and go for it. Pretty much all existing sound design kept a very high level of quality and detail, which was nice. It makes things easier, but, of course, you also want to try to match that.

How does the sound of the VR game compare to the standard console/PC version of the game? Did you have to do anything different with the spatial audio to make the sound translate to the VR game?

OS: Since we developed The Midnight Walk for both VR and flat screen (console/PC) from the start, VR was always part of the plan. That meant that early on we had to think about how interactions would differ — especially how sound would need to respond in a more procedural way.

Take something simple like a rusty hatch. On a flat screen, you just press a button and it opens or closes with a fixed animation and sound. But in VR, the player actually grabs the handle and can move it slowly, quickly, or swing it back and forth. So sounds like that had to support a wide range of motion and feel responsive to the player’s actions.

in VR, the player actually grabs the handle and can move it slowly, quickly, or swing it back and forth. So sounds […] had to support a wide range of motion and feel responsive

Early on, I spent a lot of time designing sounds to support that kind of detailed interaction. One example was the lock-and-key mechanic. In VR, when you insert the key, you could nudge it around, slowly turn it, and so on — and I designed all the subtle audio feedback to match. I’m a sucker for those small details. It felt great in VR. But later in development, a lot of those interactions had to be simplified or removed to keep things compatible with the flat screen version. That was a bit sad to let go of.

One sound that worked really well in VR, though, was the matchstick. Since it’s more like a torch and you can wield it around, we made the sound react dynamically to things like wind drag and motion. It ended up feeling really nice and added a lot to the immersion.

a lot of sounds just don’t translate well using real-time binaural algorithms — it can feel more gimmicky than immersive unless you spend a lot of time fine-tuning

As for spatial audio, we had a long internal debate about using binaural audio. Personally, I’m not a huge fan. In my experience, a lot of sounds just don’t translate well using real-time binaural algorithms — it can feel more gimmicky than immersive unless you spend a lot of time fine-tuning. That said, I lost that battle! We did end up using binaural audio, but made it optional for the player to turn it off.

In the end, I think it worked out pretty well. We took more of a hybrid approach. For sounds that didn’t translate well to binaural, we used wide stereo recordings, multiple sound sources, and real-time filtering using Unreal Engine 5’s MetaSounds to make them feel spatial and immersive without relying entirely on binaural tech.

Can you talk about your use of ambisonics, and using this multichannel spatial audio format to create a three-dimensional soundfield?

OS: The Midnight Walk was actually the first game where I used ambisonic audio — and also my first VR project. Early in development, I realized that ambisonics could really enhance the ambience in VR. It’s especially effective for creating immersive room tones or environmental beds that feel natural as the player turns their head.

It’s especially effective for creating immersive room tones or environmental beds that feel natural as the player turns their head

We ended up using ambisonics, which we created ourselves in Reaper, mostly for ambient backgrounds layers and room tones. If not using headphones, the effect is really subtle, almost unnoticeable. But in VR and especially with headphones it makes a big difference. I don’t think many players will notice it consciously, or think about it, but it adds that extra depth that makes the world feel more believable. It’s one of those things you only notice when it’s gone.

I’m a big fan of those kinds of small audio details that you don’t necessarily pick up on, but that contribute to the overall sense of presence. Ambisonics was a great tool for that, especially in a game where atmosphere is such a big part of the experience.

There were a few occasions where I wasn’t happy with the result […] It worked, but it’s as though the positioning of sounds gets a little blurred once imported into Unreal Engine

CB: There were a few occasions where I wasn’t happy with the result. As mentioned, the effect is subtle. It worked, but it’s as though the positioning of sounds gets a little blurred once imported into Unreal Engine. So for certain elements, especially the darker ambient pads under bridges, I ended up simply making a stereo sound, exporting separate files for the left and right channels, and placing these with a reasonable distance in the world. I guess it’s more similar to a stereo sound source with 3D Stereo Spread (at least I think that’s what they call it in Unreal) but with defined positions. This sort of gives you a similar result to what you can get with ambisonics especially as an addition to the rest of the ambience.

What about the Binaural Audio option for people with headphones and VR? What went into achieving that?

OS: We used a plugin in Unreal Engine called Resonance. It’s pretty lightweight, but it got the job done. We tested a few different options, and this one ended up sounding the best to me. The challenge with a lot of binaural plugins is that they often sound a bit unnatural. Many of them make the audio feel harsh or “phasy,” and they tend to lose the low-end — so deep, punchy sounds or impacts sometimes just don’t translate well.

One of the hardest parts was creating a sound you really liked and then importing it into the engine only to hear it end up completely different when processed through the binaural system

One of the hardest parts was creating a sound you really liked and then importing it into the engine only to hear it end up completely different when processed through the binaural system. Getting the same sound to work both with and without binaural filtering took a lot of back-and-forth. It was a time-consuming process, especially with such a small team.

For most of development, it was just me handling audio on top of being lead programmer and team lead. Later on, we got an intern, Joar Andersen, who I threw straight into the fire (sorry, Joar!). He did a great job and helped a lot. When his internship ended, the audio workload kept growing, and I quickly realized I couldn’t keep up alone. That’s when Christian Björklund joined the project and saved the day. He did a fantastic job and really helped bring the sound design together toward the end.

to compensate for the loss of low-end […] we sometimes layered in a low-frequency element in 2D to keep the punch

Anyway, back to binaural. One thing we ended up doing to compensate for the loss of low-end was adding sweeteners. For example, we sometimes layered in a low-frequency element in 2D to keep the punch. That way, we could still preserve the impact and weight of the sound.

CB: I understand where the gravitation towards binaural audio comes from. If you listen to good recordings from, for example, the classic Neumann head (KU100) in proper headphones, it’s mindblowing how realistic it can sound. I still haven’t heard anything even near that in a virtual environment, and most of the VR projects I’ve worked on haven’t used it for the reasons Ola mentions above.

I suspect most players didn’t even activate it. To me, this is just proof that these things are more about sound design than the tech behind it

I was told that another reason why people want it was the softer panning. Most of us don’t like hearing something 100% in one ear as that can feel quite unpleasant. To me, that’s a non-issue since you normally use a combination of reverb for distant sounds and 2D/3D mixing when sounds get nearer. On top of that, there’s the possibility to use filtering and EQ based on angle to soften sounds behind one’s back or out of sight, etc., so there are many ways to get credible positioning without resorting to plugins.

I think we should take pride in many people mentioning the immersiveness in the game, since just like Ola said, not all sounds use binaural panning, and it’s off by default unless you play VR. I suspect most players didn’t even activate it. To me, this is just proof that these things are more about sound design than the tech behind it.

Can you talk about your use of procedural sounds? What sounds were created at runtime or generated on the fly?

OS: We used procedural audio quite a bit in the game, especially for elements like wind and fire.

we created a MetaSound that combines noise generators, filters, and looping samples. That way, we could control the wind in real time using parameters like intensity, howling, and other textures

For the wind puzzles, we created a MetaSound that combines noise generators, filters, and looping samples. That way, we could control the wind in real time using parameters like intensity, howling, and other textures. It made the wind feel more alive and reactive, instead of just relying on pre-baked loops.

For fire, I started by designing a MetaSound for the matches, which, in our case, is more like a torch. Since it’s one of the main mechanics and something the player interacts with a lot, I wanted it to feel responsive and satisfying when lighting them up and wielding them around. You might not notice it as much on a flat screen, but in VR, it’s a great feeling to strike a match and move it around. Hearing it react to wind drag, movement, and speed adds a lot of immersion.

in VR, it’s a great feeling to strike a match and move it around. Hearing it react to wind drag, movement, and speed adds a lot of immersion

The great thing about building it procedurally is that you can reuse the same sound for different fire sources just by tweaking the parameters. So that torch sound actually became the basis for all our fire in the game. By adjusting things like size, intensity, and crackling, we could easily create everything from a small candle to a large bonfire, all from the same MetaSound.

Can you talk about how you used sound/audio cues for puzzle solving? What were some of your challenges and revelations in taking this approach?

OS: One of our core mechanics in The Midnight Walk is called Heightened Senses, and it ended up being a key part of how players solve puzzles. Originally, it was only meant to help the player listen for enemies — you close your eyes (literally in PSVR2, thanks to eye tracking), and all sounds get filtered and fade out while enemy sounds are enhanced. So you can rotate your head and pinpoint where enemies are hiding, how far away they are, and in which direction.

you close your eyes (literally in PSVR2, thanks to eye tracking), and all sounds get filtered and fade out while enemy sounds are enhanced

But as development progressed, we started using the system for more than just enemies. We added hidden objects, collectibles, shellphones, and other important environmental clues, and that’s when things got tricky.

Once we started layering in more sound sources, the big challenge became how to sort and prioritize everything the player might hear in Heightened Senses. Some sounds needed to be heard from a long distance, while others were close by, but in dense areas, that could quickly turn into a mess of overlapping sounds. I had to build a kind of priority system to make sure players weren’t overwhelmed. The whole point of Heightened Senses is to help the player focus — not the other way around!

the rest of the team started to realize just how powerful sound can be

What I liked most about working on this feature was seeing how the rest of the team started to realize just how powerful sound can be. When you strip away the visuals and rely only on audio, it becomes clear how much you can communicate through sound alone. It was a cool moment when other designers started saying things like, “Hey, could we solve this puzzle with audio instead?”

What was your approach to UI sounds for the game?

OS: Pretty early in development, I knew I wanted to keep UI sounds, or “informational” sounds, to an absolute minimum, or ideally, none at all. I wanted to avoid anything too “gamey” and instead tell the player what’s happening through natural, in-world sound.

The idea was to have all these “informational” sounds come naturally from the gameworld itself, not from a UI or HUD or similar.

I wanted to keep UI sounds […] to an absolute minimum, or ideally, none at all

So instead of a notification or “UI beep,” you can hear from the enemy’s own sounds whether they’re in patrol mode or searching for you and so on. It helps keep the player grounded and reminds them as little as possible that they’re in a game.

For a while, we did experiment with more classic “notification” sounds, like audio cues for when enemies spotted you or lost track of you, but for me, that completely broke the immersion. It felt too artificial and didn’t fit the aesthetics of the game in my opinion.

That said, we did keep a few of those sounds, like when you move in or out of cover, just to give the player a bit of feedback without pulling them out of the experience. But overall, the goal was always to make information feel like part of the world, not something layered on top of it.

CB: Yeah, I made one or two sounds, like when you pick up hints or collectibles from behind the little hatches. At first, there was a plan to do something when you move and look at the object in the air. I had started with a paper loop for the hints with the notion that eventually you’d be able to move it around more controlled and realistically, but that never happened, so adding some movement sound to that rotation wouldn’t work.

It’s more about trying to figure out all the parameters and limitations and then throw stuff at the wall until something sticks

Instead, it was decided to have a one-shot for when you start to get the item, and let it be pretty long so that it isn’t too quiet when you look at the item. This is (again with me) another one of those very practical solutions. I often don’t think very conceptually about these things. It’s more about trying to figure out all the parameters and limitations and then throw stuff at the wall until something sticks, then iterate from that.

Sometimes you can imagine a sound in your head and then try to make it, but here I just started with whooshes and stuff, and that just felt wrong. I ended up with an effect chain ending with reverb+delay and then tried sounds in it. I probably thought about the Coalhaven bone sounds a little bit, that we know fits into the world, so maybe something like bamboo wind chimes.

I doubt this sound would have been ok in the earlier stages, as it definitely is gamey, but as the whole event, the way it looks sort of is, too. It’s one of those “late in the production” things — something was missing and now it’s better than before, so everyone says, “Ok, that works. Great!”

Now that I think of it, it’s exactly the same with the furnace chains in Coalhaven. I can’t say it’s the best thing I’ve heard, but it works. In that case, it definitely would have been preferable with a custom music stinger, but there just wasn’t time for that. I used a few seconds from some of Joel’s music, messed around with reversed reverb, and added some metal content. That’s that. On another project, I probably would have tried to do something musical, but here, it just wouldn’t blend with the sound from Joel’s band.

What went into the character sounds and/or voice and vocal processing for:

Potboy?

OS: Potboy’s voice is actually performed by Olov Redmalm, our game director and writer. Not much processing goes into it! Just a bit of EQ, compression, and pitch-shifting sometimes. What can I say, Olov just sounds like that :)

Potboy had a lot of different moods and emotional states, and his voice library kept growing throughout development, so we eventually had to cut some of them. And the way Olov recorded was kind of chaotic. He’d just sit down and record these super long, unbroken takes of Potboy sounds, either at the office or at home, and then send them to me like: “You can probably make something out of this for Potboy’s happy state.”

That’s how it went for every mood or state he came up with.

It was a tedious but also sometimes funny part of the project, especially hearing Olov […] making Potboy say dirty words when running out of inspiration

My job was to go through all of that — cut, sort, clean up, sweeten, and finally puzzle the takes into usable voice assets. It was a tedious but also sometimes funny part of the project, especially hearing Olov nearly throw up mid-recording while doing the Potboy voice or making Potboy say dirty words when running out of inspiration. I’m honestly tempted to release some of those takes as a fan bonus someday.

For Potboy’s movement sounds, we used a procedural MetaSounds setup. It combines clay and stone textures, triggered from animation events using parameters like velocity and intensity. I also added some random porcelain rattles while he moves — I don’t know why, but it just felt right. It kind of added to his awkward charm.

I wanted the audio to somewhat mimic how sound actually travels through a pipe, becoming more muffled or clearer depending on where Potboy is

One other fun part was designing the Potboy Pipes. In the game, you can send Potboy through these long, winding pipes to reach areas the player can’t get to. You see and hear him tumbling through them, screaming the whole way. It was a bit of a challenge to get the sound to feel right, especially as he travels above your head, through walls, or into other rooms.

I wanted the audio to somewhat mimic how sound actually travels through a pipe, becoming more muffled or clearer depending on where Potboy is. That approach didn’t work well at all with the binaural system, so this is where MetaSounds really shone. By sending a normalized distance value from the Potboy Pipe Blueprint into the MetaSound, I could dynamically adjust filters, reverb, delays, and so on, based on his position in the pipe and relative to the listener position.

It’s just simple math — not physically accurate or anything — but it gave us a sound that felt right. I’m really happy with how it turned out.

Housy?

CB: As I recall, this was a pretty basic approach. I looked at it, how it feels and moves, and just made something and see how it works, then iterated from that. It needed to feel larger than you but still pretty agile, and, obviously, friendly. Even though it’s mostly cardboard when looking at it, I believe there’s quite a lot of leather sounds to get the squeakiness, and wood planks debris.

When I think back on how it sounds, all I hear is the music theme. If there’s a sonic identity to Housy, it’s that horn phrase that makes it feel a bit like an elephant so that cred goes to Joel.

The Soothsayers?

OS: The Soothsayers were added just a few weeks before release — so, as you can imagine, I wasn’t exactly thrilled at first. Both Christian and I were already knee-deep in unfinished audio tasks, and suddenly we had to make room for a whole new character.

The idea came from Olov Redmalm, our writer and game director. He also voiced the Soothsayers and really wanted to include them to expand the lore he had written. We had a heated discussion about it — me saying, “There’s no time to do this.” But in the end, we somehow managed to pull it off. And looking back now… I’ll admit it: I’m glad we did. It adds so much to the world and the story. (I stand corrected, Olov!)

as with most voice work, Olov did his thing and just sent it over. He had used pitch shifting to double his voice to create a feeling of two voices

Since the character has two heads, I originally wanted to give them two completely different voices — maybe one male, one female — but still have them speak in unison. I thought that contrast could be cool. But there just wasn’t enough time to explore that idea.

That said, I think Christian did a great job with the sound design in such a short amount of time. And if you listen closely, you might notice a little Star Wars influence in there — Olov’s a huge fan.

CB: This one got thrown in very late in the process, and as with most voice work, Olov did his thing and just sent it over. He had used pitch shifting to double his voice to create a feeling of two voices. I had some ideas I wanted to try, and I remember Ola talked about making it into a male and a female voice, but there was simply no time to design anything properly, so I just ended up recreating a variation of what Olov had done, but in a little bit fancier way.

The Thief?

OS: The Thief (or The Ghost), was a fun one. When she charges at the player, all she does is scream hysterically. Constantly. It’s pretty intense and stressful. It was pretty fun to make that sound. I chose that approach for two reasons. First, it ties into her lore and background — I wanted her scream to express all this frustration and hatred rooted in what happened to her. And second, I just loved the dynamic contrast. When you go from this eerie silence in the mines to her suddenly spawning in front of you, screaming at full volume. That kind of jarring shift added to the tension and gets your adrenaline pumping a little extra.

I created a MetaSound that functions like a granular synth. I made a screaming loop from various female screams […] And then the MetaSound samples grains from it in real time.

For this sound, I created a MetaSound that functions like a granular synth. I made a screaming loop from various female screams I found in my libraries, that slowly ramps up from screaming to hysterical. And then the MetaSound samples grains from it in real time. That allowed me to control filters, pitch, and intensity based on how close she is to the player. So when she’s chasing you, the scream ramps up the closer she gets, which makes it feel like she’s right on top of you.

I also added an ambisonic background layer that plays whenever a ghost is in the room. It’s a subtle, low-frequency drone mixed with whispers — like a supernatural room tone. It gives the ghost a kind of signature presence, even when you can’t see her.

I added a weird, granular, almost electrified transition sound for when she passes through solid objects

And since she can move through walls and solid matter, I added a weird, granular, almost electrified transition sound for when she passes through solid objects. So when you can’t see her and hear that sound, you know she will probably pop out from a wall nearby.

That sound was made from recordings of crumpling paper bags and rumbling stones, which I then processed through an almost maxed-out compander and MeldaProduction MGranularMB to give it that unnatural, crackling quality.

The Craftsman?

CB: That one is big. It was definitely a challenge, especially since he actually moves around and does his thing while you’re playing. I wanted it to be as bassy and massive as possible, but there still has to be some room left for everything else. There’s a lot of long, pre-delayed reverbs and echoes on the sounds he makes. For vocalising, I probably tested to pitch shift down anything I can think of and see what matches. I have some high-frequency recordings of my own, and I like the fact that you can get some really good library content done with 100kHz microphones today.

The heart has […] some liquid movement coming from what I assume is a water dispenser or fuel tank being tilted

The heart has all kinds of sound sources in it. I find it tricky to make something organic and gooey but also big, and of course, the clay thing. There’s some liquid movement coming from what I assume is a water dispenser or fuel tank being tilted. Someone in the team said he always gets a bit nauseated by the heart sounds, so mission accomplished, I suppose.

The Moonbird?

OS: Overall, there’s not a ton of processing on her voice — mostly reversed reverb and some pitch shifting. But there was a lot of work that went into processing her lines, since most of them were tailored specifically for each cutscene, and often varied from line to line.

I wanted her voice to follow her movement and expressions closely throughout every scene, to let the sound design add something extra to the visuals and make the cutscenes feel more vivid and dramatic.

There’s also always a subtle layer of fire behind her voice. Occasionally, it bursts into wooshes or small fireball-like explosions to underline certain words or movements.

Sometimes she appears huge and evil, sometimes cunning or mysterious, and at the same time, there are lots of small details happening in the background, like pipes bending, rumbling stones, or sudden motion. I tried to use sound to emphasize those things. For me, details like that are super important to make a scene feel alive.

There’s also always a subtle layer of fire behind her voice. Occasionally, it bursts into wooshes or small fireball-like explosions to underline certain words or movements. It’s not in-your-face, but it gives her presence this elemental, powerful feel that builds her character.

The Molgrim?

OS: The Molgrim was a little bit tricky since she was supposed to sound like an old lady, but finding the right tone for that was hard. It was important that she didn’t come off as goofy or cartoonish — we still wanted her to feel serious and like a real threat. She will kill you, after all.

I experimented a lot and eventually landed on a blend of her voice, ice crackling, and stone textures — all run through a vocoder. That helped give her this layered, unnatural quality that still felt grounded and menacing.

I built a MetaSound to handle all of that procedurally — everything from her “walking” to smaller body movements.

For her movement sounds, I imagined her like a giant snail dragging itself slowly across the ground. I built a MetaSound to handle all of that procedurally — everything from her “walking” to smaller body movements. That system gave us a lot of flexibility, since we could trigger sounds not just for her locomotion, but also for things like head turns or subtle body shifts, all without having to manually author unique sound clips for every single animation.

The ‘Shellphones’?

OS: The shellphones were actually one of the very first interactable objects we implemented in the game. Back then, we only had three or four of them, each with different recordings. The idea was that they would act like strange, old recording devices the player could pick up — delivering lore, cryptic hints, or eerie echoes of the past. We wanted them to feel a bit unsettling, like they were witnesses or echoes from another time.

One cool feature I built specifically for VR was a distance-based filter; the closer you held the shellphone to your actual ear, the clearer and less distorted the audio became.

We went for a vintage, lo-fi gramophone sound, layered with a bit of tape wobble and a distorted impulse response to make it sound as if the audio was actually being played through the shell itself. That gave them a tone that turned out really nice.

One cool feature I built specifically for VR was a distance-based filter; the closer you held the shellphone to your actual ear, the clearer and less distorted the audio became. It worked well technically, but when we started testing the game with players, no one really understood the mechanic. Most people just held it in their hand and couldn’t make out what the shellphones were saying at all. So unfortunately, we had to cut that feature.

I actually experimented with the MetaSound effects. Instead of redesigning it, I used amplitude modulation and some phasing to distort it a bit and thin it out

CB: They were already in when I joined, but I had to make a new idle-sound for them. They have this radio-tuning noise, and at one point, I even asked if we could have something more discrete and with shorter attenuation, then just use a bit of spot light to find them instead. But everyone was so set on using sound to locate stuff, so what can you do? This was one of the few places I actually experimented with the MetaSound effects. Instead of redesigning it, I used amplitude modulation and some phasing to distort it a bit and thin it out.

I did re-process all the voices, but they already had a good feel to them, so I recreated a similar effect. There was some feedback about how much tape wobble and stuff like that to address. It’s fun to process and distort voices as much as possible, but there’s that point where it becomes a distraction from the storytelling.

Can you talk about your collaboration with composer Joel Bille? The score lends so much to the horror, unease, and feeling of gloom in the game!

OS: Joel Bille and his band Bortre Rymden (which roughly translates to Beyond Space or The Outer Space) did a fantastic job with the music. It was super nice and smooth to work with Joel.

We worked closely throughout the whole project, constantly sharing ideas back and forth about music and sound design, how the music should sit in the mix, when there should be music versus just sound effects, how and when to leave space for each other in the mix, and how to transition between the two.

Since I handled all the technical implementation and audio systems, Joel could just ping me on Discord with ideas or feature requests, things he wanted the music system to be able to do.

Whenever we were working on a new cutscene or a specific area, we’d often just call each other and say, “Hey, what are you thinking for this part?”

We’d talk about the mood, in what key the music would be in, and the atmosphere. From there, we’d try to weave our work together in a natural way. It was super easy to adapt to each other’s work.

Since I handled all the technical implementation and audio systems, Joel could just ping me on Discord with ideas or feature requests, things he wanted the music system to be able to do. That led to a setup where he could shape and implement the music the way he wanted, directly in the game.

that tight integration between music and sound really helped shape the mood and atmosphere of the game

We also tried to keep the music system as simple as possible, so I built a priority-based system. That way we could easily manage different layers like exploration music, danger zones, chase themes, stingers, and so on, without it getting overly complex. It gave Joel creative freedom without us having to micromanage transitions or logic.

It was a great creative partnership, and I think that tight integration between music and sound really helped shape the mood and atmosphere of the game.

What went into the sounds for the ambience/backgrounds, for the sounds for the scary things you hear in the dark? (Any helpful indie sound libraries? Custom recordings?)

OS: From a technical side, most of our ambient sounds were handled using a UE5 plugin called Soundscape. It manages and triggers layered ambiences based on Gameplay Tags, which made the system flexible and decoupled since we could trigger sounds from anywhere in the game logic.

most of our ambient sounds were handled using a UE5 plugin called Soundscape. It manages and triggers layered ambiences based on Gameplay Tags

The nice thing about Soundscape is that it’s pretty modular. You can build out palettes and layers and then let the system respond dynamically to the game state. But I’d say the downside is that it can be a bit tedious to work with, especially in a game like ours. It seems better suited for large open-world environments, so we definitely had to work around some limitations to make it work for our game.

CB: It was a bit different depending on locations. For more room tone type of stuff, or base layers, there’s just so many ways to design, I usually just combine recordings with all sorts of effect chains and see what happens, then pick out the gems. Usually I want to throw things in the game and just play with it like that for a while to see how it works.

I like to use quite busy recordings, typically field recordings, and then use iZotope RX to extract the softer, far away sounds and clean out the rest.

Then there are oneshots like animals/creatures in the forests and swamps that are triggered on random positions. I like to use quite busy recordings, typically field recordings, and then use iZotope RX to extract the softer, far away sounds and clean out the rest. This way, you can get material that already sounds distant. Even with some bad noise reduction artifacts, it’s often just fine once you add them on top of an ambience. They just blend in.

For other sounds, I just cut apart animal sounds, pitch, blend, and add several types of reverb to get it to just be something more abstract. For the forest, we accepted more “real” bird sounds, but the swamp got to be a bit more fantastic.

Speaking of sound libraries for this project, I mostly use the Soundly Pro material and sometimes the old Sound Ideas 6000. I just got to browse through Mattia Cellotto’s Animal Hyperrealism series through another project. I have to give that a mention as it’s very impressive and useful stuff!

What was your favorite location in the game to sound design? And what do you like most about your sound work for there?

CB: Maybe the passage with the Dark before entering Headville, when you get sort of stuck in that state with the dark noises for a while to figure out the puzzle. It has a little bit of that more abstractness I mentioned in the beginning.

I like how the mechanics of the puzzle turned out and the loud noise as her bullets whiz by and hit the cardboard figures.

OS: It’s hard to pick one, but I would say the Craftsman’s Heart. I think that level is the one that both aesthetically and soundwise sits best together. I liked how the part with the cardboard puzzle turned out, at the square where the witch is trying to shoot you. I like how the mechanics of the puzzle turned out and the loud noise as her bullets whiz by and hit the cardboard figures.

Another highlight was the end scene of the whole game. That was a lot of fun to work on too, even though it was super rushed. I wish we had more time to polish it properly. It came together in the end, but I would’ve loved the chance to give Kenneth Bakkelund’s amazing artwork and animations the full treatment they deserved.

What went into the ambience inside Housy?

CB: That would mostly just be Ola’s procedural fire and some generic roomtone with some muffled “wind from the outside” elements. And of course, the records or movie sound on top if you activate them.

What was your favorite single sound to design? What went into it?

CB: I like the flying machine. It’s just a little inconspicuous creature/machine in between levels that I don’t think most people take much notice of, but I enjoyed trying to give it a little voice, and I think it was the first sound I made if you don’t count ambiences.

OS: I’d say the Grinners. I really liked how their alien, animal-like behavior came through in the final sound design. The way they react in their different states: waking up, noticing the player, or charging, combined with their hysterical screams and galloping footsteps, just felt very organic and scary. Even the subtle mechanical sounds of their masks opening and closing helped sell the creepiness.

I also really liked their idle sounds — that unsettling vocalization they make when they’re just lurking around. You can hear it echoing between the walls even when you don’t see them. That eerie feeling that they’re always nearby, just out of sight. That kind of builds up psychological tension.

I stumbled upon this whale grunt in one of the BOOM libraries we use […] I felt like I’d found the base voice of the Grinners

But getting there was tough. I actually tried a lot of different approaches, and none of them worked. With time running out, I was seriously stressed and pretty close to giving up. Then I stumbled upon this whale grunt in one of the BOOM libraries we use. I started messing around with it, and suddenly it just clicked — I felt like I’d found the base voice of the Grinners.

From there, I built it up with more layers: whale grunts, Tasmanian devils, and probably a bunch of other stuff I’ve forgotten. It was a lot of experimenting and processing and honestly a bit of a lucky shot.

When they charge the player, I also wanted to emphasize their size and weight, like something massive is coming at you. So I added an extra heavy footstep/body movement layer to really sell that. The idea was that you hear this huge rumble and screaming coming at you and you just know there’s no way out; it’s already too late.

What were your biggest creative challenges on The Midnight Walk ?

CB: I got to do all the easy stuff. Ola already had a good handle on the monsters, for example. Otherwise, that definitely would have been it. I don’t think people realise how difficult that can be if you want to avoid the usual pitched-down, growling orc thing.

I did the Dark (the eyes) and that took some work and iterations before landing on something that felt right.

I did the Dark (the eyes) and that took some work and iterations before landing on something that felt right. It starts off pretty harsh sounding, and then it gets a little nicer and lighter every time it shows up. Actually, the first encounter was much worse for a while. I don’t know how many layers of screeching and screaming it had but it was very loud. I needed to take it down a bit, mostly for the way it works in context with what’s happening before or after, if I remember correctly.

In a more general term, that organic aesthetic is challenging. I’ve been working quite a lot with Tarsier studios and it’s the same thing there; you can’t just do the simple tricks. Anything that starts to sound remotely like sci-fi, fantasy, magic, gamey, or just too “unnatural” breaks the illusion. It needs to feel organic and sit in the world, but at the same time, you can’t go for realism either. So yeah, it’s a narrow road to wonder.

OS: As Christian already mentioned, we really tried to keep things as organic as possible. Coming up with something that felt fresh, that hadn’t already been done a hundred times before, trying to avoid the classic “pitched-down orc growl” trap takes a lot of effort. It’s such a well-worn path in creature design, and falling into it —even accidentally— felt like a failure, haha. And that was honestly one of the hardest challenges for me.

I guess that’s part of the process — failing your way forward until something finally clicks.

I’s spend a ton of time and effort crafting a unique voice for a creature, only to step back and realize: “Damn. That just sounds like another pitched-down tiger / orc.” It’s kind of heartbreaking when that happens, like you took this long creative detour and somehow ended up right back where everyone else already went. But I guess that’s part of the process — failing your way forward until something finally clicks.

I don’t say that the creature sounds in The Midnight Walk are unique. I really don’t. But that was at least the end goal, and that takes lots of effort and time. It’s super easy to tip over to something that just sounds artificial and not organic at all.

What were your biggest technical challenges?

CB: So, MoonHood is a fascinating bunch. Their game is very creative, organic, and full of life. Well, I felt that the Unreal project and the team structure were just the same. I got the feeling that they used Unreal more as a sandbox than I’ve seen before. I honestly didn’t think you could work like this and still get it together in time. At the same time, it’s also one of the few projects I’ve worked on that kept its original timeplan for release, so who am I to judge? I’m excited to see what kind of means Ola will use in the future to try to enforce things like naming conventions and defined pipelines on these wildlings, if it’s even possible.

they used Unreal more as a sandbox than I’ve seen before

What I’m saying is that it was a bit of a challenge to navigate the project. Often to get somewhere to work on a specific sound I had to ask around and eventually have a bunch of notes like, “Place this thing there, find that rock, start the game a few meters behind it, walk through there, pick up the thing.” Similarly, just to find the right assets, sometimes you could almost follow the creative process by their different names throughout the project structure.

we were developing VR and flatscreen versions simultaneously; it’s actually the same game, not separate builds.

OS: One of the biggest technical challenges was that we were developing VR and flatscreen versions simultaneously; it’s actually the same game, not separate builds. You can switch between them at any time. That meant every sound we created had to work in both contexts — and that’s not as simple as it sounds. Some interactions worked very differently depending on whether you were in VR or not, and yet the same sounds had to make sense and feel right in both versions. It added a whole extra layer of complexity to every decision.

Another major challenge, as Christian mentioned, was naming conventions and the overall inconsistency in how things were implemented. Every time we had to add a new sound, it turned into a kind of detective mission: figuring out how to trigger it, where it should happen, and what exactly was going on in the code or blueprint.

the same sounds had to make sense and feel right in both versions. It added a whole extra layer of complexity to every decision

As team lead, I was constantly nagging about this throughout the entire development: writing naming convention docs and reminding people in meetings… and I think it eventually got through, but probably a bit too late to save us from the chaos.

Kudos to all my wonderful and super creative teammates that made this wonderful game, but naming conventions and consistency is not their game, haha!

Can you talk about your approach to mixing The Midnight Walk?

CB: From my perspective, the sound design was in a good state early on, so it was quite easy to just make sure things are reasonably mixed at once there. It took a bunch of custom attenuations and tinkering to get some things right. There is always the occasional sound that needs extra attention to blend in while still being audible all the way.

Some of the assets had a pretty quick trip from microphone into the game during the process, so it took some detective work to […] find the correct original take

The dialogue took some work as it was recorded on many different sessions and locations. I decided to collect everything, sort through it, and get it all in one big Reaper project so that I could listen and process everything coherently. Some of the assets had a pretty quick trip from microphone into the game during the process, so it took some detective work to figure out what was what and where to find the correct original take. The nice thing was as soon as that was done I could just export everything for a character and replace it in one go. It’s one of those things where you start to wonder in the middle of it all if it’s actually worth it, but then when it’s just so quick and easy to work with, it simply makes the actual mixing a breeze and therefore lifts the overall quality.

OS: Early in development, I put together a document with general mixing guidelines, basically target dB and LUFS levels for different sound categories like music, narration, NPCs, explosions, and so on. It was never super strict, more like pointers to make sure we were all aiming in the same direction. I think both Christian and I stuck to those levels pretty well, and the mix kind of held together naturally over time.

The last thing I did before release was just to throw a light compressor and limiter on the master, and I added a subtle ducking system for the narrator

That said, we were always paying attention. We regularly discussed the mix — what was too loud or too quiet in certain areas — and made adjustments weekly. So we kept things under control as we went, instead of trying to fix everything at the end.

We had planned to do a full final mix pass across the whole game, but to be honest, by the end, we were just trying to get everything in before shipping. So that didn’t really happen. The last thing I did before release was just to throw a light compressor and limiter on the master, and I added a subtle ducking system for the narrator to help him cut through the mix a bit better.

In the end, I think the overall mix holds up well, especially considering this wasn’t a big AAA production. It’s a small indie game, made on a tight budget with a short timeline. And with that in mind, I think we managed to hit a really solid level of quality.

Your sound team used Unreal Engine MetaSounds, and the UE5 audio pipeline. How did this benefit the audio on The Midnight Walk? What were some advantages of working this way? What were some challenges?

CB: Ok, here we go… Well, there’s definitely an advantage to having a built-in, totally integrated sound system. With third-party sound engines, there’s always an extra step or two, none of them are perfect, and there’s, of course, the extra cost involved. Other than that, let’s just say I don’t get the hype. When MetaSounds was introduced with UE5, I was curious. But as soon as I got to look at it, I had a hard time seeing in what way this would make my life any easier. Maybe it’s unfair to compare it with something like Wwise, which is quite expensive, but it was actually announced together with Nanite (UE5’s virtualized geometry system) and Lumen (UE5’s dynamic global illumination and reflections system). Above all, I’ve noticed how studios see this as a way to cut back on that cost. Sure, you can technically achieve quite a lot, but as a tool, it’s not nearly as refined as the alternatives, especially when it comes to the user experience.

I’ve noticed how studios see this as a way to cut back on that cost. Sure, you can technically achieve quite a lot, but as a tool, it’s not nearly as refined as the alternatives

This project was the first time I actually got to try it out properly. And I had the advantage of someone smart doing all the setup and preparations before I got started. Even then, I had a hard time following how all the buses, groups, classes, effects, etc. go together, not to mention parent/child overrides. Nothing is easily readable. I really miss the visual overview. The actual MetaSounds editor is ok, I guess, but I just hoped for a more coherent system to handle all audio.

In my view, when I first saw Wwise many years ago, I remember thinking, “Ah yes, there it is!” Someone just cracked how it should be designed with the containers in a tree system, one for sounds and one for the mix setup. You throw things around with ease without having to deal with the fact that every little detail is in its own .uasset that needs to be created, placed, and named, and then deal with redirectors should you actually want to move or rename something.

when it comes to node-based editors, I like building relatively complex things in Max/MSP. Compared to that, this feels ten years behind

Issues I can have with Wwise are generally about the Unreal integration, but as long as I work in the standalone editor, it’s just great. Not to mention the profiler is fantastic, and there was just nothing like that in Unreal at that time. (To be fair, we didn’t have the very latest version. I know there should be some tool like that now, though). I’m not saying they should have made it just like Wwise, but why not learn from what actually works great already?

And yes, the actual MetaSounds editor, sure, it’s flexible. I’m just not sure I did anything in there I couldn’t have done in Wwise with a little occasional help from Blueprints. Also, when it comes to node-based editors, I like building relatively complex things in Max/MSP. Compared to that, this feels ten years behind. Anyway, I get it. Everything is based on the Unreal Editor workspace. I’m sure it made sense to build it like that> And yes, those more procedural sounds that Ola set up at the beginning of the project were cool to see. To end this rant on a positive note, I can only hope that this leads to Audiokinetic (Wwise) and Firelight (FMOD) stepping up their game to keep offering affordable alternatives.

The benefits were clear: no third-party licenses, and everything just ‘works’ within the engine.

OS: Yeah, that’s true. It was a decision I made early that we should go with UE5’s audio engine and MetaSounds only for this project — partly because I wanted to explore what MetaSounds could do on their own, but also because we were on a tight budget.

The benefits were clear: no third-party licenses, and everything just works within the engine. That meant fewer surprises across platforms, and more predictable performance. Plus, from a technical and programming point of view, I really liked the level of control MetaSounds gave me.

The flip side is that you have to build a lot of systems yourself — stuff that FMOD or Wwise just give you out of the box. Unreal’s audio tools still lag behind in some areas. For example, like Christian mentioned, the audio workflow in UE5 can be kind of a mess. Assets are scattered, there’s no great overview of your mix or signal chain, and it’s easy to break things without realizing it which makes it pretty error prone.

the audio workflow in UE5 can be kind of a mess. Assets are scattered, there’s no great overview of your mix or signal chain, and it’s easy to break things without realizing it

Honestly, I could probably rant for a while about what could be better in UE’s audio tools. But overall, I think the decision worked out. I don’t regret it, and I’d probably make the same choice again for our next project. (Sorry, Christian.)

That said, I do think MetaSounds are a bit overhyped right now. It seems they’re more focused on sound synthesis, which I don’t really understand. But for gameplay audio, it’s not always what you need. Still, I like the direction it’s going, and I think it’s going to become a really powerful system.

What have you learned while working on the sound of The Midnight Walk?

OS: First of all, I think you learn something from every project you work on — not just in terms of skill, but also about yourself and the people you work with. I’m a perfectionist, and while that can be helpful, it’s also something I struggle with, because it often gets in the way.

If you’re open and generous with what you know, you’ll always get something valuable back in return.

The Midnight Walk taught me to let go a little, to focus less on perfection and more on what makes the game feel alive and just do the job. That the “crappy” sound you just threw in as a placeholder might actually be the one that works best. That imperfection can add personality and uniqueness.

I also learned a lot from Christian and Joar — and that’s the beauty of collaboration. If you’re open and generous with what you know, you’ll always get something valuable back in return.

CB: I learned Reaper! I actually never worked with it before more than the occasional experiment or specific batch job. There wasn’t any particular reason, but I’ve been wanting to give it a real chance for a long time, so I skipped Ableton for this project (for the most part). I managed to get some useful scripts done using AI and got a reasonably fluent workflow.

I learned Reaper! […] I managed to get some useful scripts done using AI and got a reasonably fluent workflow.

The timing was perfect as I got to process almost all of the dialogue and did a big portion of the footsteps. I really enjoyed being able to do that all without any custom tools, but instead be able to automate all the tedious steps.

Other than that, there’s always a bunch of new knowledge gained with each project. You pick up little things here and there just by having to design new sounds and also listening and dissecting what the others have done. I think I’m a little bit better at handling sub bass than before.

Then, of course, all the Unreal audio stuff would have been extremely difficult without Ola to guide me through it and answer the same questions over and over.

A big thanks to Ola Sivefäldt and Christian Björklund for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at the sound of The Midnight Walk and to Jennifer Walden for the interview!