Only a handful of film franchises have hit the 10+ films mark. There’s Star Wars (including Rouge One and Solo), James Bond, Star Trek, all the Marvel Cinematic Universe films that tie into each other, X-Men, Batman, the Wizarding World franchise that includes the Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts films, and of course The Fast Saga (including Hobbs & Shaw).

Not an easy feat to sustain a storyline over decades. In fact, the first film in The Fast Saga, The Fast and the Furious, was released 20 years ago!

Formosa Group‘s MPSE and 2x Emmy Award-winning supervising sound editor Peter Brown, 2x-Emmy and MPSE Award-winning sound recordist Paul Aulicino, and 2x-MPSE Award-winning sound recordist Charlie Campagna talk about their on-going experience of recording and editing for The Fast Saga, the new vehicles they captured for F9, their go-to gear, their effects mastering and editing process, and much more!

F9 – Official Trailer [HD

Peter, you’ve been working on The Fast and the Furious franchise for seven films now? Or has it been all nine of them?

Peter Brown (PB): If you think about The Fast and the Furious films, you may think they’re about cars but they’re really about family. And if you look at our sound team, you’ll see it’s also a family. Paul [Aulicino] was on the first film, and our mix recordist/mix tech Bill Meadows was on the second film through to the current one. So in our sound family, every single film is represented.

Paul Aulicino (PA): Including Hobbs & Shaw, which was a spinoff.

It’s great that you were able to keep this franchise in the family! What are some of the key aspects of the sound that have carried through this franchise from film to film?

PB: Dodge Chargers. Dom (Vin Diesel) is always driving a Dodge Charger.

Traditionally, it has been supercharged with some kind of 8-71 blower on the front with the three round butterflies. That was such an iconic part of the first The Fast and the Furious.

And now in this latest one, he’s driving a twin-turbocharged version. So that’s kind of the main through-line in terms of cars.

PA: He has to have a domestic car, except in the first film though. Didn’t he drive a Mazda RX-7 in the first film? He had a Mazda, but he was always talking about, “I got to have American muscle.”

PB: And he usually destroys his Charger. He didn’t get a chance in the third film, but he sacrificed it in the fourth. It died in a cave. It gets sacrificed for the good of humanity. That’s the big through-line.

PA: In this film, he has two classic Chargers. I believe he drives one and he has one in his barn that he’s always working on. That’s the original Dodge Charger.

We went out and recorded this Dodge Tantrum, which is a famous 1650-horsepower custom-built Charger. It’s allegedly valued at $600,000. Or somebody tried to sell it for that.

It has a twin-turbo boat engine in it. It’s crazy sounding. Jay Leno, years ago, drove it around Burbank.

So you recorded a Dodge Tantrum? Did you record any other cars from the film? Or did you find other cars to record to create the sound of the cars that we see on screen?

PB: Nothing gets recorded on-set other than the dialogue. That’s the only usable production sound in the movie.

PA: What’s funny is that a lot of the cars you see in the film are custom-built and they all have the exact same engine in them: the LS3 engine. So they all sound exactly the same. So even though there’s the Mercedes-Benz G-Klasse W460 in Fast & Furious 6, it has an LS3 engine in it. Or there’s that cool Camaro in 2 Fast 2 Furious; it has the same engine.

So we have to go out and find the actual engine or else all of the gearheads who are watching the films are going to think we didn’t do a good job.

Can you tell me about some of the cars that you tracked down for F9 and how you recorded them?

PB: There was the Tantrum we mentioned earlier. And that was used for the car in the film. That’s kind of a rare situation, but it was a special car and defies the rule that we just said. But it wasn’t used that much in the film.

We would use the sound of that car in other places when Dom drives a similar kind of Charger.

The opening of F9 is an entirely vintage scene that takes place in 1989 at an old NASCAR race. So we had to dig up old NASCAR cars to record and get those engine sounds correct. We went out to the Irwindale Speedway and miked up two of those and drove them around for an afternoon and recorded the sound.

Recording 1980’s NASCAR for ‘F9’

Another one that was difficult to get was the Nobel M600 that Queenie (Helen Mirren) drives Dom around while he’s in England. It’s this super-fast, really cool supercar that only exists in England.

There wasn’t one anywhere in the United States that we could find. We’ve had that problem in the past with a Koenigsegg in one of the films. We had to get the only one that existed, which was in Miami. And then there was the Lykan Hypersport that they jumped between buildings; that car doesn’t exist anywhere except maybe in the United Arab Emirates. It’s a million-dollar car.

Recording the Toyota Supra doing a power slide for ‘F9’

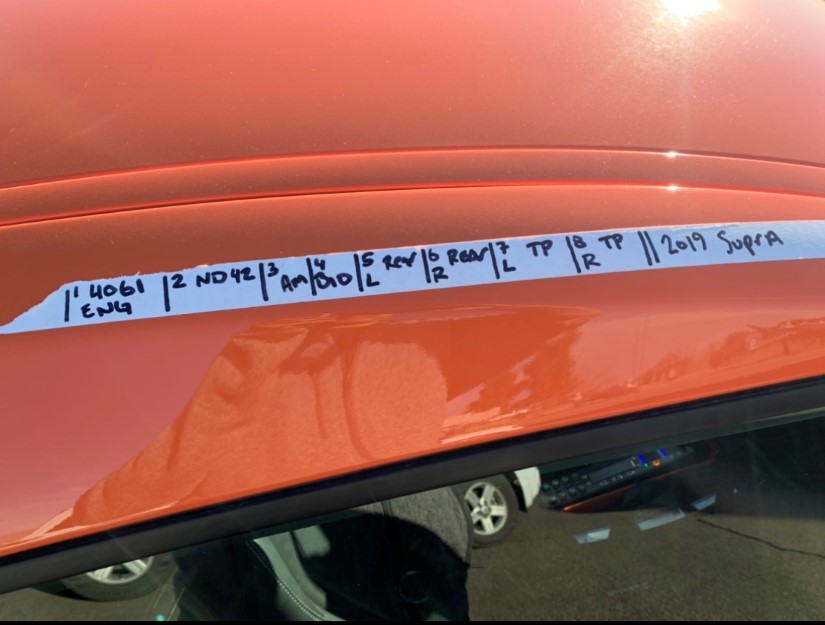

PA: For F9, we recorded the new Toyota GR Supra, which hadn’t been out for years. When we recorded that in 2019, it was going to be a big surprise because the film was originally going to be released in 2020. So no one had seen the new Supra.

Now, two-and-a-half years later, it’s not a big surprise to anybody. But it was really cool that we saw it before it actually came out.

Charlie Campagna (CC): It was really cool to see that car come back and it was fun to record because it was sporty and tight sounding.

CC: Some of the vehicles are so hard to find that we can’t get our hands on them, like the Mercedes-Benz Unimog-based truck/double trailer thing called “The Armadillo” in the film.

PA: The guy who builds the production cars, Dennis McCarthy, he builds all the cars (for just about every film now it seems). He’s also heavily involved in desert racing/off-road racing Trophy Trucks.

Charlie and I actually went out to a muddy racetrack where he drove a Turbo Off-Road Mud Racer into the ground for us, which is really cool. It’s capable of jumping 15-feet high. We put the mics on board and by the time we were done, the recorder was caked in mud. We were surprised that anything was recorded.

Turbo Off-Road Mud Racer recording for ‘F9’

CC: It was literally layered in red mud and when we took the layer of mud off, I was able to press stop to turn the recorder from record to stop. And it was still working. Everything was still cruising, but it was really crazy to see it all just caked in mud.

It turned out to be one of the coolest sounding vehicles that we recorded because it was all open. But with that amount of mud, you’d think that the recorder wouldn’t be working. And as for the mics, it looked like we had fondu-ed all the Rycotes in mud-cheese; it was pretty gnarly.

PB: Gear has a tough life.

CC: We’ve had a lot of microphone sacrifices along the way, I would say.

Peter has a really nice cigar box filled with interesting things.

PB: We had an Isuzu Bakkie that caught on fire and burned up a Sennheiser 418. I still have its charred carcass. That was an expensive day but it was a nice recording. We barely had time to rip the Zaxcom Deva out of the vehicle before all hell broke loose. Of course, the mic gave that warm, rich Sennheiser sound even while being consumed by fire.

And then there’s the DPA 4062s that we learned should not be wrapped around the drive shaft. It’s not good for the cabling; it does not help the cabling at all.

PA: We have to crawl under the cars; we have to get in under the hood. We have to try to place all of these microphones. And sometimes we have additional people come out with us to help. And this one guy (who will remain nameless) got under the car to place a mic. He goes, “Does this thing move?” And I’m like, “What are you talking about?”

He was zip-tying one of the microphones to something underneath the car and it turns out that it was the driveshaft. So when the car drove about five feet, the mic was dragging on the ground because it snapped in half.

PB: For the Armadillo in the film, one of the best big diesel days that we ever had was with this drifting truck. This guy, Mike Ryan, who does a lot of the stunt driving and indeed drove that Armadillo in F9 as a stunt driver, he created this truck to compete in the Pikes Peak race. It’s a semi-tractor-trailer with a big front end and a cab and it can haul a big trailer, but it could also drift.

So this truck could smoke all the wheels and fly around corners and race up Pikes Peak. And that was a lot of fun to record because it was just a big beast of a diesel.

So that would be one of the things that we’d use in something like the Armadillo, to play the part of a big military vehicle.

CC: Didn’t he pop a wheelie in that thing? It was ridiculous.

Usually, we’re recording these super hot, exotic cars and then this semi comes up and blasts the horn. And we’re like, “Okay, this is interesting.” And all of a sudden, it just starts whipping around us as if it was a souped-up Toyota Corolla drifter. It just looked ridiculous and I couldn’t stop laughing for the first five takes because it was so fast! It would just whip around us. And it was a semi!

We were having a blast that day, just watching the thing whip around. This truck is totally a test of physics.

Custom-built semi-tractor-trailer doing stunts for ‘F9’

PA: I rode in it for one of the takes and that was a little intense. The driver just said, “Get in and hang on.” Next thing you know, I’m flying against the window. I’m flying into him because he’s doing donuts in the middle of this airstrip where we were recording.

Modified ’47 Hudson landspeed recording for ‘F9’

PB: There’s also that ’47 Hudson landspeed and road-race truck. It’s an incredible machine: a 7.3 liter powerstroke diesel that this guy Randy Simmons rigged up to allow his quadriplegic friend to set a landspeed record at the Mojave mile.

PA: He modified the Hudson so that he could be in the car, but his quadriplegic friend could drive it with their mouth. It set some record for this street race that goes from California to Arizona. It’s something like a hundred-mile race and he averaged 110 miles an hour, on the street in a pickup truck.

CC: It was one of the most beautiful cars too, I have to say. It was classic/vintage-looking, but when it drove past you, it would have this turbo diesel sound. It sounded amazing and looked amazing, and had almost a steampunk vibe about it because it was super modern but it looked old.

PB: It belched that black smoke…

PA: …that stays in your clothes all day. He said his buddy found this ’47 Hudson in a barn and the stipulation was that he could have it if he turned it into a race car. So he sure did.

What were some of your go-to mics and recorders for capturing all of these vehicles?

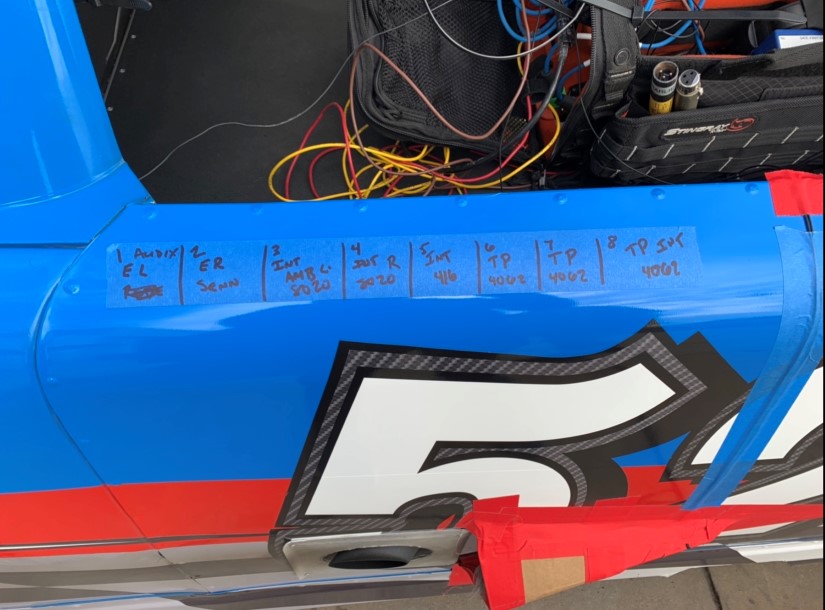

CC: We like using DPA lavalier mics. We like that these lavalier mics have different models with 10 dB sensitivity of differences.

So, if we’re recording a really large, loud car, we can use the DPA 4062, which has a 20 dB attenuation versus the 4060, which could handle speaking levels. So we can put the 4062s in the engine compartment.

And if it’s a loud car, like a NASCAR or that dirt racer we had, we used the 4062s on the exhaust because everything else would just blow out and distort.

For interiors, we usually experiment because every car is different and we usually come out with a plethora of microphones. Depending on what we have available that day, we’ll use different mics but we usually prefer the Schoeps microphones for the interiors.

We’ve experimented throughout all of our recordings, from using an M/S setup to microarrays. And lately, we’ve been doing ambisonic recordings inside the car. When we master those sounds, we keep it raw so you could choose the type of layout of the ambisonics format to match what would be appropriate for the scene.

And what about recorders? What do you find is most effective to have in these cars?

CC: We like to use recorders that have timecode. We’ve tried every recorder on the market pretty much. Back in the day, Paul recorded using the Zaxcom Deva V.

PA: I did use the Deva but that was temperamental. If the vibrations were too much, it would literally blow out in the middle of a recording.

PB: Yeah, the low-end would make it drop out.

CC: We’ve actually road-tested recorders like the Zaxcom Deva V, which is a really fine piece of gear but it was more of a production recorder. So we realized right away: do not use the Deva V.

And by that time, Sound Devices started coming out with their recorders and we realized that if we replace the hard drives with solid-state drives that it would work better. And nowadays, all Sound Devices recorders use removable media.

We like to time code all of the recorders together so when we split apart and have our recorders separate from each other, they’ll still be syncable later on.

We like to time code all of the recorders together so when we split apart and have our recorders separate from each other, they’ll still be syncable later on. We definitely make sure we do that.

We like to capture long, long recording takes so it’s easier to sync it in the Pro Tool session later. So we might be recording eight hours on one car, but we’ll do chunks of 45 minute takes. We’ll do all the maneuvers in that 45 minutes so when it’s time to sync stuff together, it’s a lot easier.

PA: Instead of going through a hundred clips, we only have to go through four.

PB: Syncing what’s onboard with what’s exterior is really hard because the onboard mics are always moving around in relation to the exterior mics that we are holding. If you don’t have long takes or time code to sync everything up, you’ll never be able to figure out what’s going on because any sync point, like a door slam, happens at one moment on the onboard recorder but it happens a second later on the recorder of Paul who is standing 1100 feet away down the runway. Long takes, time code, and door slams are essential to syncing up the recordings.

CC: Another trick is to do lots of mouth clicking or any type of short transient you could hear in the file so you can visually see things lining up, just to make sure it’s all kosher.

Recording stunts in a NASCAR with side exhaust using a custom mic baffle

Do these cars have air conditioning? Are you turning the air conditioner off and rolling up the windows, trying to get a quiet interior sound?

CC: So many times we’re asking the driver, “Can you roll the windows up? And can you turn the air conditioner off?”

A lot of these drivers are almost like celebrities because they’ve worked on all the franchise movies, not just the Fast films, but James Bond and other action films. They’re not used to being told what to do, especially, “Turn off the air, please.”

So a lot of times these guys are sweating bullets after sitting in the car. After a number of takes, they’re like, “I got to get out of this car and just get some air.”

And usually, they team-play with us really well, but it’s an interesting request to have the windows rolled up because we’re in the desert.

PB: Nick Nicholson, Brad Beavin, and Brad Kelly, those are all guys on Dennis McCarthy’s crew who basically come out and act as stunt drivers. They have to drive these cars so fast on a boiling hot day with the windows rolled up. I can’t even believe they talk to us anymore.

Up until ‘Fast Five,’ we used to have somebody sitting in the car with the recorder… and that was me.

PA: Up until Fast Five, we used to have somebody sitting in the car with the recorder… and that was me. It got really, really hot in there, as I recall.

I remember the one guy just peeling out and doing donuts and the whole inside of the car is filling up with tire smoke and it’s 110 degrees in there. I think after that, we figured out we didn’t need a human in there. We could just secure one of the recorders in there, which was nice.

PB: It’s better for Paul’s lungs this way.

PA: And there’s no passenger screaming, ruining the take.

Recording a NASCAR with side exhaust and custom mic baffle

What was the most challenging car to record for F9?

CC: I think the NASCARs were kind of challenging because of how loud they were. They kept blowing out microphones.

PB: I’d say the side exhausts were a problem and we’ve had to deal with them before. In The Fast And The Furious: Tokyo Drift, the Monte Carlo had side exhaust, and we did an okay job on that.

Then we did Steve Kelso’s NASCAR — also side exhaust — and we had two more cars as well. But, I think we kind of nailed it on this one. Charlie made up this wind baffle system that would go on the side and shelter the little 4062 mic from the wind. And it worked remarkably well.

Charlie made up this wind baffle system that would go on the side and shelter the little 4062 mic from the wind.

PA: That recording session we actually did at the racetrack. So it wasn’t in our normal recording venue, which is out in the desert where it’s quiet. So we literally had to shield the mics from random noise. I think there was a quarry next door. And there was an airport really close by. There were all of these backup beeps.

CC: Yeah. That was the biggest challenge. It’s not necessarily the most difficult car; it’s the environment. Some of the environments where we recorded the cars were windy or near a factory. We’ve had barking dog problems.

PA: The location we normally go to, which is the California City Airport, recently had a boom of development around it. It was pretty much an abandoned area up until about three years ago, but now there are dogs. There was a kitty litter factory that was always working.

We need to find a quieter place at some point. But that’s the most challenging thing.

Recording 1980s NASCAR doing donuts for ‘F9’

CC: Another interesting thing about a NASCAR race car is that it only turns in one direction, so we would have to make sure we’re on the other side of the turning radius.

And at the same time, that type of car wouldn’t do particular maneuvers that were necessary for the movie because they just lap in circles. That presents a unique challenge when you’re trying to record something that only turns one way.

Every time we recorded a NASCAR, when they tried to turn a little bit — to make a maneuver to just turn around — it was difficult. It has a long turning radius. And a lot of the time the tire hits the body fender well.

PA: And that blows a tire out and now it’s an hour of downtime waiting for them to put a new tire on it.

What about the Noble M600? Did you get to go to England to record that car?

CC: No, but we went to Hawaii and that was really fun!

PB: Yeah, for those Rat Rods.

There are so many challenges to recording these cars. Everything has to line up. You have to get a location. You have to have all your recordists available on that day. You have to have the gear. The gear has to work. The batteries have to work. The weather has to be good. Edwards Air Force Base can’t be flying jets and causing sonic booms, or doing helicopter testing around your location.

There are so many things that you have no control over.

There are so many things that you have no control over.

It can’t be too hot a day because these cars produce so much heat that they will overheat very easily. And then you have downtime. The cars can’t break. The drivers actually have to be able to drive or be willing to drive because so much of the character of what we lay down comes from the personality and general level of insanity that the driver has and whether or not that car is built to do donuts or fast stops or quick maneuvers. Everything has to align.

And in the case of the Nobel M600 that Queenie drives, we had the additional strain of a global pandemic descending upon us. Nobel, which is this bespoke car company in England, was generous enough to lend us one of their great cars and a driver to come down to the Bruntingthorpe Airfield in England and the production recordist for F9, John Casali, recommended two recordists to go out there and capture its sounds.

This was literally the week of March 13th, 2020. Nobody really knew if they were going to be dead in a week or not. And these two brave souls — recordists Jerome McCann and Gary Dodkin — went out there as the world was shutting down and somehow made it happen.

…we were never sure that we were actually going to get the correct vehicle so we had already cut the whole scene twice with our best similar engine.

It was an awesome job under really insane circumstances. For the most part, they record humans, not cars so they had to scramble around and find all these lavalier microphones, travel to Leicestershire, avoid the plague, and the rain — I really got the sense that the rain was insane — then a clutch died… it was epic all around and they nailed it.

Until we got that material, we were never sure that we were actually going to get the correct vehicle so we had already cut the whole scene twice with our best similar engine. Once we had the actual, proper car sound, we tore the whole scene up and recut it a third time.

Can you talk about your process of going through all of these recordings? You mentioned using time code to help sync all your recordings, and that sounds really helpful…

Also, what were some of your challenges in editorial? After the recording process is over, what’s your approach to matching these recordings to what’s happening on-screen?

CC: Before editorial, we master the recordings. One of our challenges was finding dependable SD drives — little SD cards that could handle being flipped back and forth.

We have multiple recorders running during a session and so afterward I’d have up to five SD cards containing different things. When we put that into Pro Tools, everything is already time coded so I would just spot it to time code and it would automatically sync up. That’s the easy part.

I will chop up the sound in increments of five miles per hour. So we’ll have 5 MPH, 10 MPH, 15 MPH, 20 MPH, etc.

We do long takes, and we usually record in increments of ‘miles per hour.’ So we’ll do a maneuver, like a parking lot maneuver that’s extremely slow. Then we’ll do top speed maneuvers, and so on. I will chop up the sound in increments of five miles per hour. So we’ll have 5 MPH, 10 MPH, 15 MPH, 20 MPH, etc. And that way when someone’s cutting, they could actually see all the files lined up with the miles per hour in the name. So if they know they’re cutting something that’s fairly fast, they could go up towards the 50 miles per hour files and grab those or audition those.

This was made possible by using Soundminer in conjunction with Pro Tools. I would consolidate the tracks, which would actually be Recordist 1, Recordist 2, Recordist 3, and sometimes Recordist 4, and 5. And then all the interiors, which would be onboards and interiors. All those files will be just one take with different, multiple perspectives.

I would export that into Soundminer, give it the metadata, and name it. And it’s done. Then I would do the next take and export it into Soundminer. That way the naming management is so much faster than clicking on every single clip in Pro Tools and renaming it.

From there, that goes to our editors, our sound designers, Peter and Stephen Robinson, who take it from there.

PB: Stephen Robinson is really the chief architect of the sound editing for all the vehicles in the film. Various folks will add different parts, but Stephen is the fastest and the best and knows all of these cars.

Stephen Robinson is really the chief architect of the sound editing for all the vehicles in the film.

So he’ll take this material that we produced out in the field — and generally, he’ll work from Soundminer so that his takes are lined up — figure out what he wants, and typically he’ll run it through some type of VST processing rack so he can sculpt what frequencies and what sounds he wants to hear out of a given engine before it even gets into Pro Tools.

Generally, I think he likes to accentuate the low end using something like Waves R-Bass. Also, we’ll use something like the Waves L3 for a limiter, and then sometimes add in a little bit of musical, light distortion to the files and export those from Soundminer directly into Pro Tools.

In Pro Tools, he’ll move the pieces around to get them where he wants them, and will often use Serato’s Pitch ‘n Time Pro to change the speed, the RPMs of the engine, or to get different bits to fit together. It’s a very, very useful tool, especially so in The Fast and the Furious where every car goes from slow to extremely fast and then keeps shifting more and more and more, going up into 10th gear, 11th gear, 12th gear — faster and faster all the time.

In the climax moments of some of these big action sequences, Stephen will find that even though we’ve recorded the car redlining at 7,000 RPM, he’s going to need to use Pitch ‘n Time Pro to bring it up to 9,000 RPM — some impossible speed for that particular car.

But when it’s thrown in with everything else — with the music, the dialogue, the family — it sounds appropriate.

What was the most challenging scene to construct in terms of these vehicle sounds?

PB: That’s a difficult question to answer, but I’m going to take a stab and say that our fearless leader, director Justin Lin, really enjoys tasking us with something that’s completely impossible — more impossible than the last time — and saying to his visual effects team and to his sound team, “Make me believe this.”

I think that moment in F9 was when the Armadillo flips over, it’s this gigantic multi-segmented three-piece articulated military vehicle. That was a supremely challenging moment to sell. And it was done through the miraculous mixing skills of Frank A. Montaño and Jon Taylor on the Hitchcock Dubbing Theater at Universal Studios.

Frank A. Montaño and Jon Taylor…somehow took all the pieces that we threw at them and made sense out of it…

They somehow took all the pieces that we threw at them and made sense out of it, often by eliminating certain muddy sounds and accentuating the best character accents. Frankie would lower Jacob’s car engine, ask for more tire grinding here and a touch of suspension whomp there. Jon would build up the music, then drop it out quick. Gradually, something magical emerged that expressed the colossal weight of this vehicle lifting up in the air and flipping over onto its back. We tried a ton of different things to get that to work.

PA: When the Armadillo is just about to come down on top of the car, I think Stephen used some sort of lion roar or pitched animal scream.

Another thing that’s challenging in that scene is after you do all that work on it, or Stephen does all that work on it, the director might not like this chunk in the middle, this VFX that just does not work. So they change the picture on us; they’ll make 50 cuts into this masterpiece we’ve already crafted. And now we have to go back and try to fix it with the same vigor with which it was created, and that makes it even more challenging.

Overall, what was unique about your approach to recording and designing the sound of the vehicles for F9?

CC: On the recording side of it, I started incorporating video with our car records — just with a GoPro attached to the handheld microphone — and that serves as a guide track for when I would sync everything together.

There’ve been times where it would come in handy in the editing phase, where you would have this reference video with the sounds we recorded in the desert with all the maneuvers. I would get feedback from Stephen and the other sound editors that it was really handy to have these video reference tracks in conjunction with our field recordings.

Recording the Modified Pickup Truck doing slides on a dirt road

You can scan through it in Pro Tools and see that the car does a turn there, and does a turn there. You can just scan through visually and see what the car is doing before you start auditioning. You could only do that in Pro Tools. So with all the car records that we do now, we also make a Pro Tools session of the car record in case the editor wants to approach editing that way, or before they start using Soundminer to take the sounds to a new level.

So that was something we did on the recording side that was interesting and unique. It allows us to have a library of car recordings that are really thorough. When we start working on Fast 10, for instance, we’ll start by looking at recordings we did previously. And since we have reference videos, we’ll know what the cars were doing because we can actually see it.

And since we have reference videos, we’ll know what the cars were doing because we can actually see it.

This is something that we’re trying to do and it presents new challenges when we do it, but we try to do it when we can.

PB: I’d say that what’s unique is that, by working with awesome people for all these years and having a studio and a director that really believes in teamwork and family, our shorthand just feels so efficient. We have done so many of these films together, not just us folks in sound and in post-production, but with this director, with Frank Cuomo (our incredibly supportive Post Supervisor over at Universal), and with Dennis McCarthy (the car genius).

We don’t need to explain to the stunt drivers what we’re going to do. We get to the location. We pull out our gear. We start to mic things up. It’s kind of a ritual, but it’s so fast. And we just keep on bringing what we’ve learned from the previous films to the next film. That is only possible because everybody is just having a good time and really respects everyone else and works together.

And we started this process standing on the shoulders of the giants of car recording: Roger Pardee and Jay Wilkinson…

So each time we go out, we know how to get the basics of the car, but maybe we want to get what the rear wheel is doing. Or maybe we want to overinflate the tires. Or maybe we want to take advantage of a broken axle on an old Maverick and get some piece of hopping, chirping tire that we’ve never done before. Or maybe we just want to haul the spare tires off the back of the trailer and drop them on the ground and get that bouncing sound, something we never thought of doing before.

We just keep on building on what has come before. And we started this process standing on the shoulders of the giants of car recording: Roger Pardee and Jay Wilkinson, who did some of the most incredible recordings of the ’70s and ’80s.

In a word, it’s “teamwork.”

PA: Since we first started doing this back on Tokyo Drift, I think we’ve cut our recording session times in half just because we’re so efficient now. We know exactly what we need to do. So we can do two cars in a day, whereas 10 or 12 years ago, we were doing one car a day. Familiarity is what has helped.

A big thanks to Peter Brown, Paul Aulicino, and Charlie Campagna for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at the sound of F9 and to Jennifer Walden for the interview!